The Great Sovereign Debt Intervention is here, with leaders now eager to prevent rising instability in America’s bond market. Their solutions, however, will not only prevent a calamity but stimulate risk assets without the aid of central bankers. The era of “Treasury QE” (quantitative easing) awaits us.

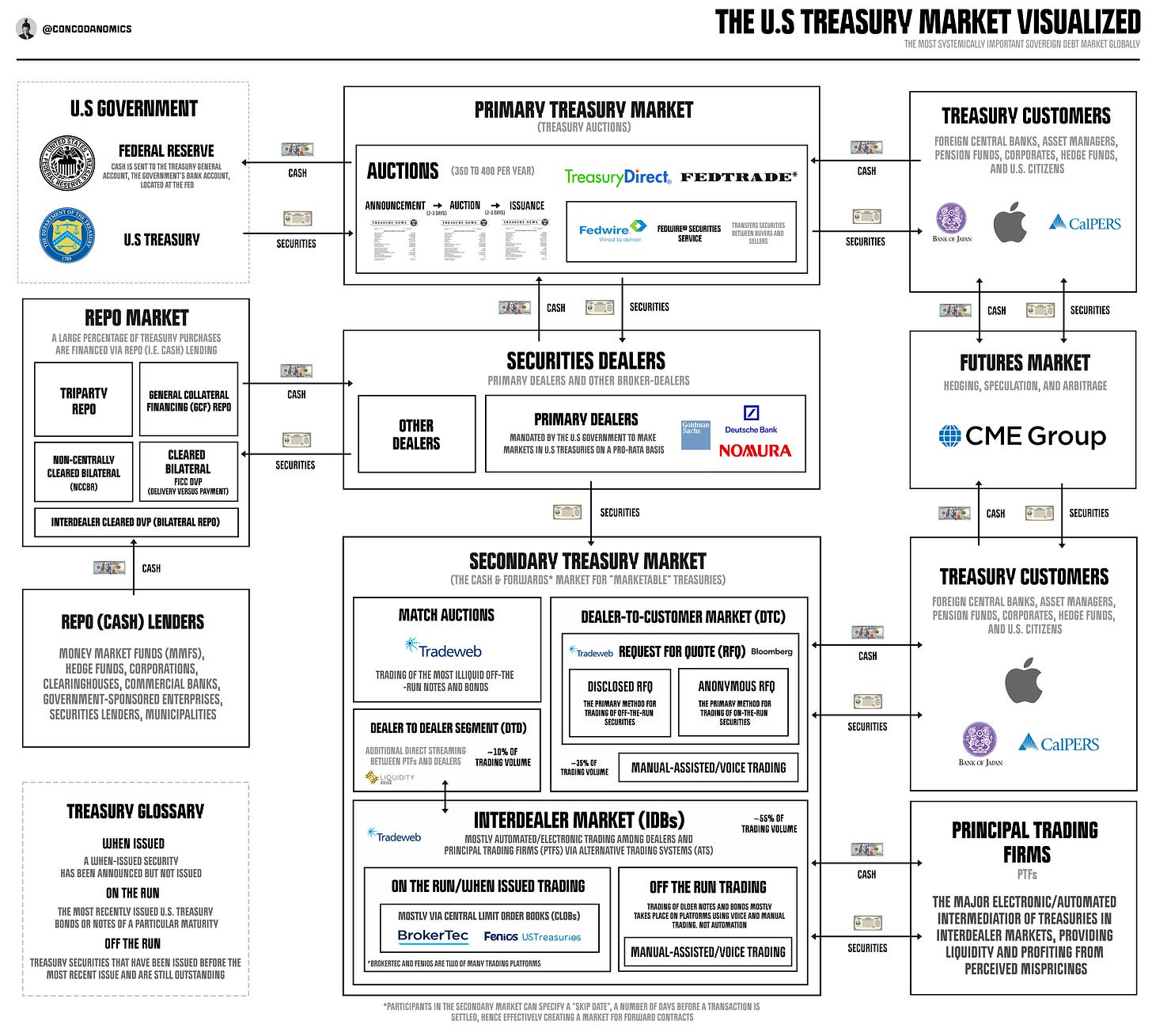

After we warned late last year about rising illiquidity in America’s sovereign bond market, leaders have begun to respond. The unintended consequences of previous policies, regulations, and interventions can no longer be ignored. Earlier this month, authorities revealed their latest mechanism to paint over the cracks in the U.S. empire’s liquidity goliath. Officials announced the first Treasury buyback program in just over two decades, designed to thwart illiquidity in America’s $23 trillion sovereign debt market.

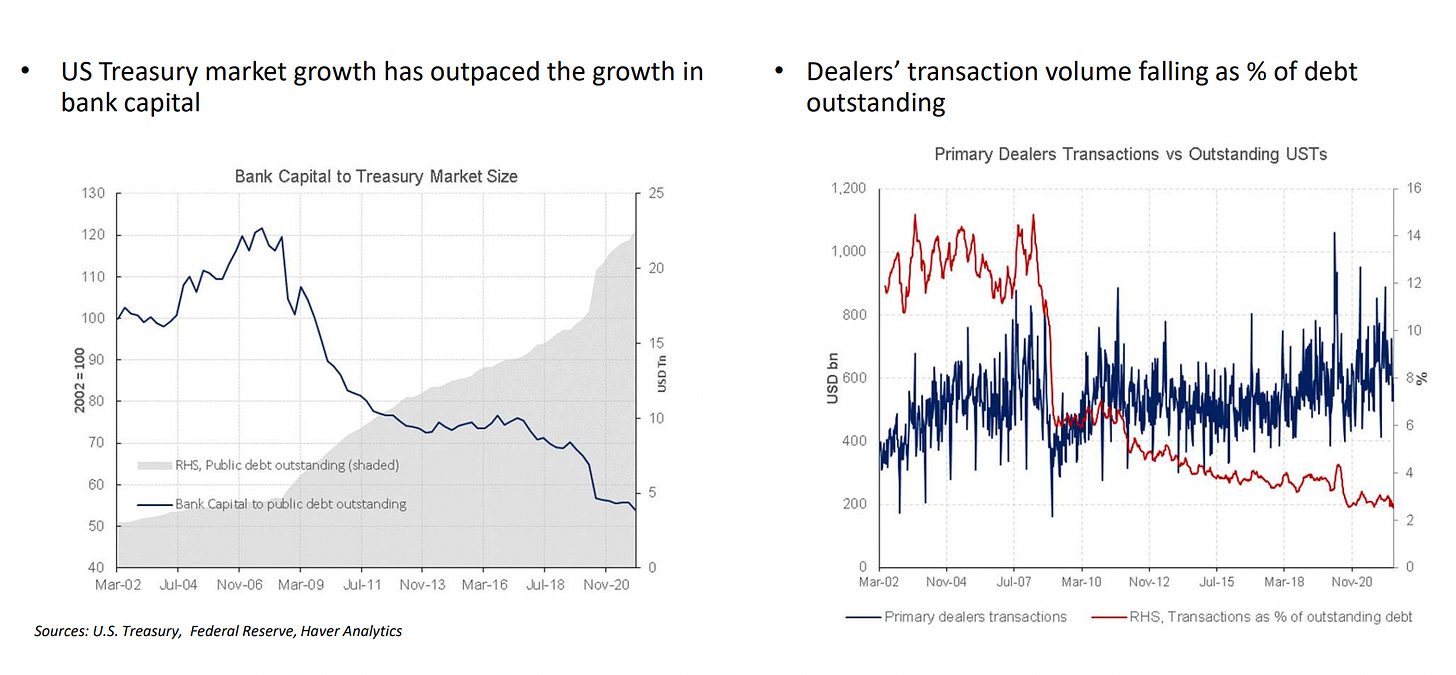

Over the last decade, the post-financial crisis regulatory establishment has forced the biggest liquidity providers in the Treasury market to retreat. The major players have pulled back from market-making, just as America embarks on its greatest debt expansion in recent history. Regulations such as Basel III and the Dodd-Frank Act have hindered the major liquidity giants through balance sheet constraints, such as the Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR) and Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR). The cost of making markets in Treasuries is ever-increasing.

Meanwhile, to achieve its global and domestic aims, the U.S. empire is set to issue around $1 to $2 trillion of (net) Treasury debt each year, all while the ability of financial actors to absorb such an amount is dwindling. Monetary leaders, however, have acknowledged the endgame. The rules and restrictions they have enforced over the last decade have been designed to transfer systemic risk from the big banks to the sovereign (state) level. But to also keep the global liquidity machine churning, they will need to conjure up more monetary alchemy.

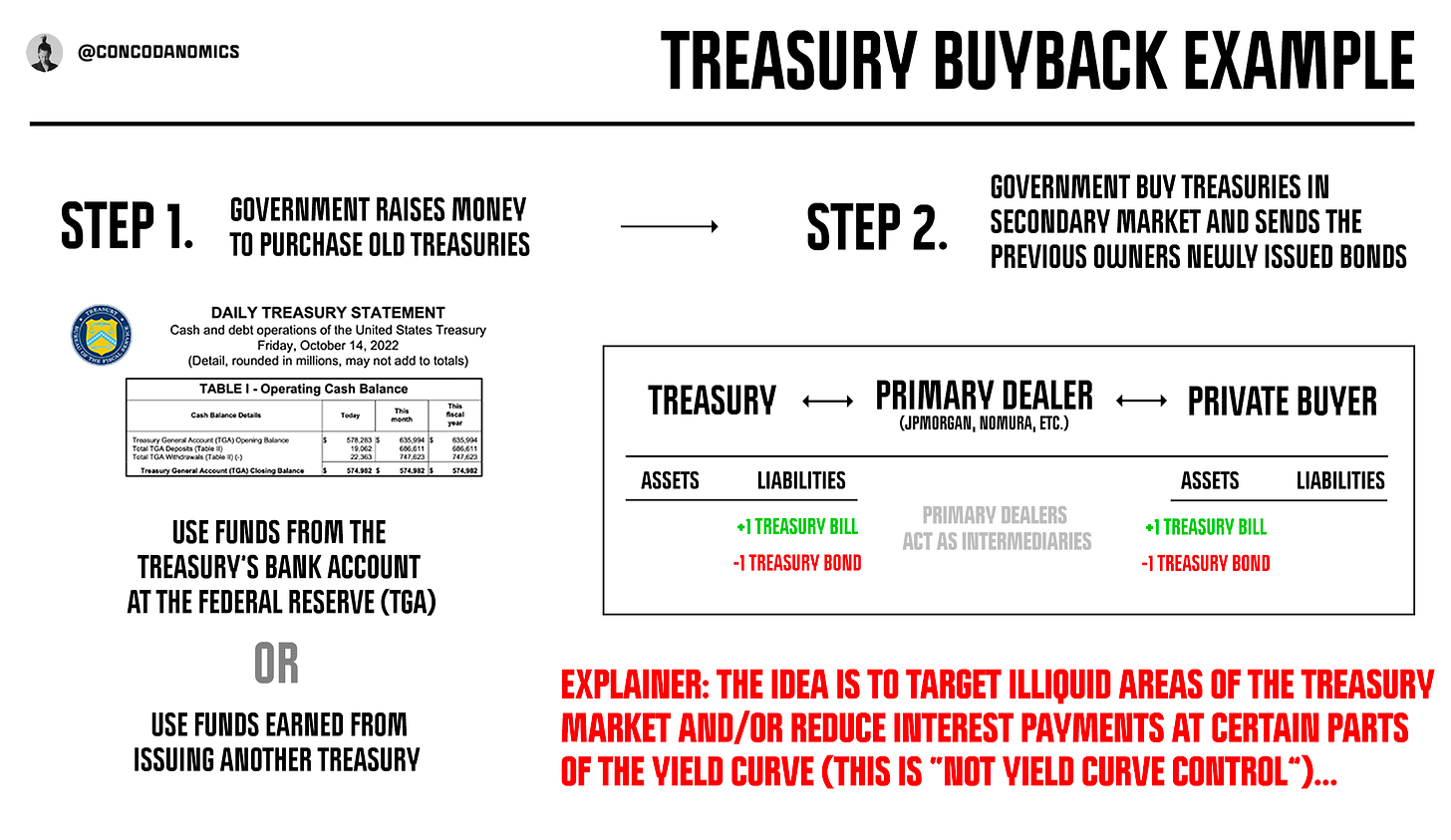

Although the details aren’t yet set in stone, the U.S. Treasury will be conducting a Treasury buyback program in 2024 and onwards. It has two objectives: to improve “cash management” — jargon for reducing the volatility of the Treasury’s bank balance (the TGA) — and to boost liquidity in the secondary Treasury market.

Buybacks will also enable the Treasury to replace expensive bonds with those that cost less to service. What’s more, much like the Federal Reserve, the Treasury will become a “dealer of last resort”, acting as a buyer of illiquid bonds when no other participant is willing. Using funds from either bond sales or its bank account at the Fed, the U.S. Treasury will purchase existing bonds in the secondary market (via primary dealers such as JPMorgan and Nomura) to boost liquidity and maybe even suppress yields. Lower yields equal cheaper expenses.

Though Treasury buybacks give them the ability to greatly influence markets, officials have stated that the announced program won’t be extensive enough to act as a bailout in times of stress. If turmoil erupts, other measures will be enacted.

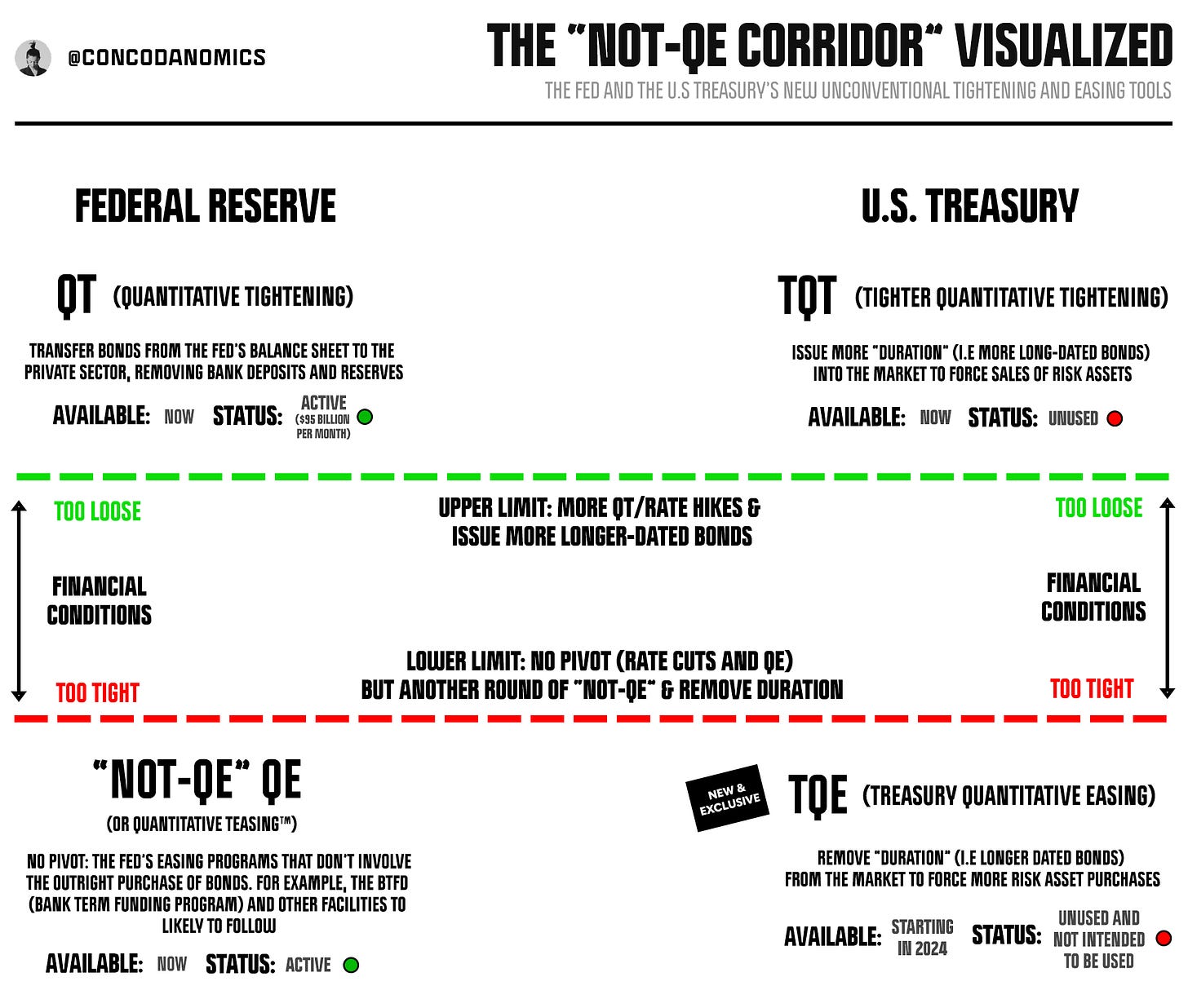

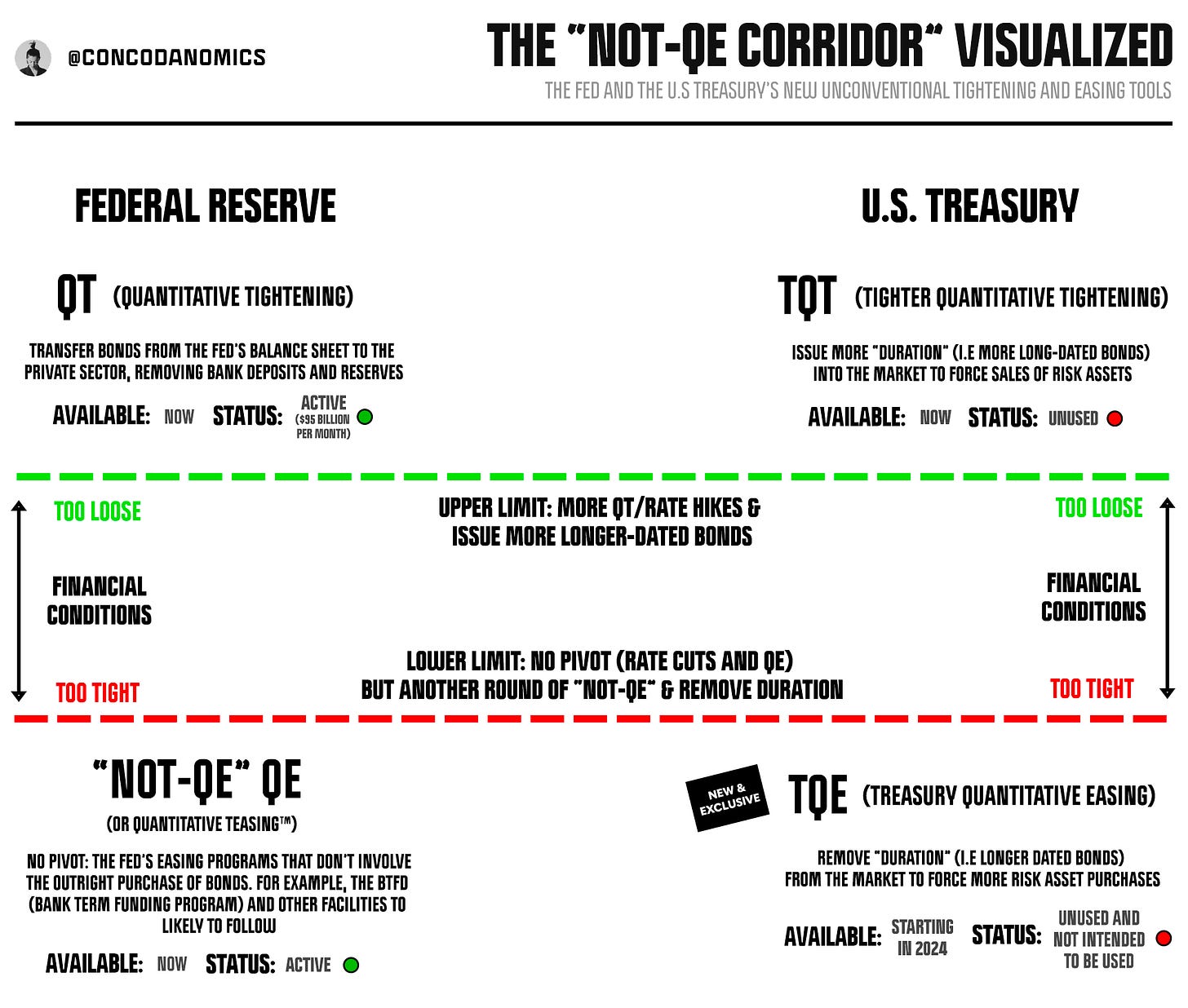

Today, though, the number of tools officials can employ to quash volatility has grown more limited than ever before. The Fed can’t initiate a full-blown pivot of rate cuts and QE without reigniting animal spirits, undoing all efforts to tackle inflation. Its toolbox remains scarce. Instead, officials at both the Fed and U.S. Treasury are doing everything in their power to continue a tightening cycle without reversing course. With a pivot off the table, they have been forced to implement what Conks calls the “Not-QE corridor”, the new unconventional toolbox.

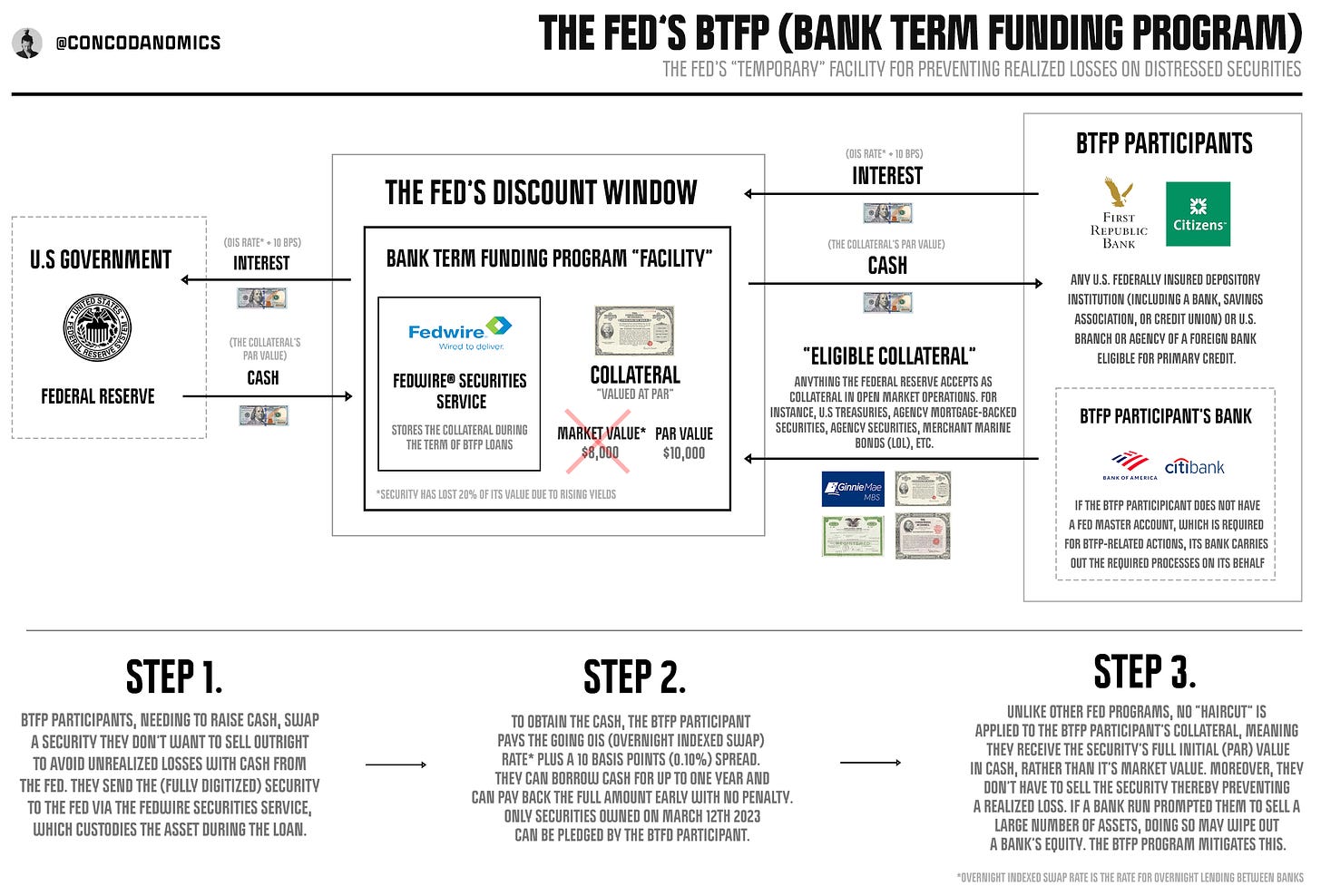

Much like the Fed’s “Global Jaws”, which depicts the global dollar rates corridor, the “Not-QE corridor” has an upper and lower limit. When the upper boundary is reached, financial conditions have become too loose for the Fed to sit by idly. More rate hikes and QT will follow. Conversely, when the lower limit is reached, financial conditions have tightened enough to warrant Fed intervention. The U.S. central bank has no intention of pivoting until it’s reached its 2% inflation target, so it must invent “stealth QE” facilities, like the BTFP (Bank Term Funding Program).

The Fed has been using all the easing and tightening tools available in its armory, but the U.S. Treasury has yet to wield any. At the upper limit of the Not-QE corridor, the Treasury has chosen to avoid deploying “TQT”: Tighter Quantitative Tightening. With TQT, monetary leaders attempt to tighten conditions further by reducing the Fed’s balance sheet at a faster pace while issuing more long-dated bonds to the market. The greater duration risk of longer-dated bonds causes investors to sell riskier assets to fund these purchases.

Meanwhile, at the lower limit of the Not-QE corridor, the Treasury does not possess any concrete tools to stimulate asset prices. After all, that’s the job of the Federal Reserve. At the start of 2024, however, buybacks will commence, enabling the prospect of Treasury QE.

If inflation remains higher for longer, and the Fed breaks something else not worth pivoting over, the Treasury could join forces with the U.S. central bank to help ease financial conditions. While the Fed implements more Not-QE measures, the Treasury uses buybacks to stimulate risk sentiment. Previous buyback programs have not been used by Treasury officials to specifically stimulate asset prices, yet this time could be different. If politics at the Treasury and the Fed align during a period where a pivot is undesirable, the Fed’s independence could be bypassed.

The first of two mechanisms they could use to stimulate financial assets via buybacks is simple: remove duration risk from the market by buying back longer-dated bonds and swapping them with shorter maturities. Swapping 30-year bonds for 2-year notes will be stimulative. Still, to truly make this “quantitative easing for Treasuries”, officials would have to announce that this is what they’re doing in advance, thereby mimicking the psychological effects that traditional QE (buying bonds with newly printed bank reserves) has on riskier assets. Right now, the Treasury has no plans to employ this type of easing. Proposed buybacks will be “duration neutral”. But it’s feasible if desired.

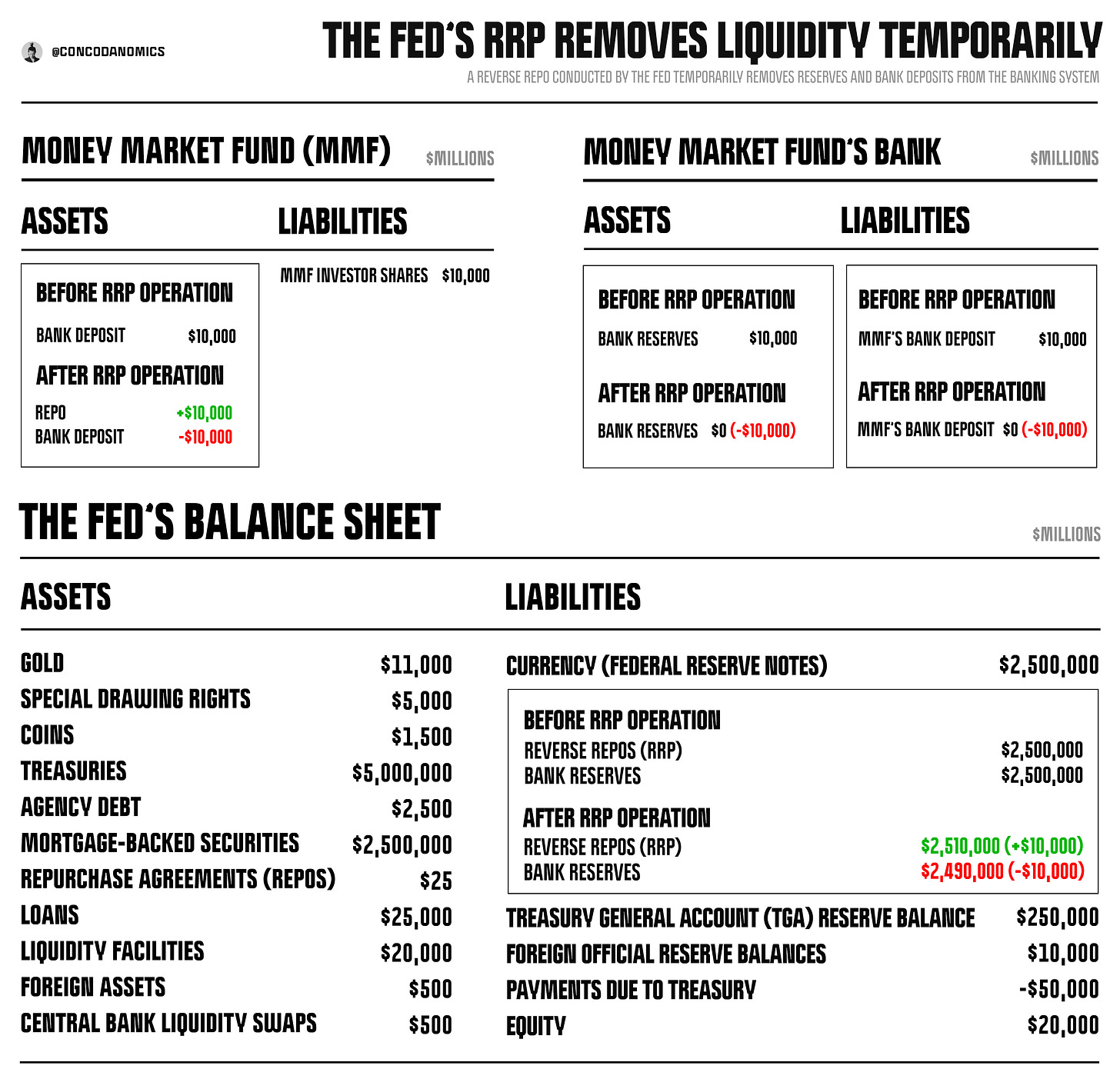

Then, there’s the second Treasury QE mechanism, which this time boosts liquidity in the financial system and potentially increases risk-seeking behavior: Treasury buybacks where the newly issued bond is funded with cash drained from the Fed’s RRP (reverse repo) facility. Unlike the first kind of Treasury QE, easing occurs without Treasury officials ever intending to loosen financial conditions. If a money market fund (MMF) withdraws cash from the RRP facility, a Treasury buyback is all that’s needed to boost “net liquidity”.

Before this type of Treasury QE takes place, the MMF had originally invested in RRPs (reverse repo agreements) offered by the Fed. The result was a stable stream of overnight income for the MMF but a net draining of liquidity from the financial system. RRPs are what Conks calls “reserve neutralizers”. Bank reserves and deposits are “neutralized” .i.e temporarily removed from the banking system and replaced with the most illiquid cash-like investment: an RRP issued by the Fed. Unlike other short-term investments, cash is locked in the triparty repo platform — which the Fed uses to process RRP transactions — till 3:30 pm the following evening. The price to pay for receiving free money from the Fed is “trapped” intraday liquidity and often inferior returns.

When the MMF invests in an RRP, its commercial bank destroys the MMF’s deposit and sends reserves to the Fed. Once received, the U.S. central bank transforms these reserves into an RRP liability on its balance sheet. Liquidity, in the form of bank deposits and reserves, has been “neutralized”.

But when the money fund decides to partake in a buyback by purchasing new bills the U.S. government is offering, this process “de-neutralizes” reserves and deposits, adding once-trapped RRP cash back into the banking system. Overall liquidity has expanded once again. This type of Treasury QE, however, can only be influential if MMFs are willing to unwind their RRP positions with the Fed and take part in upcoming buybacks. If investments other than RRPs, like bills and repo, offer superior returns, only then will this be stimulative. Ultimately, in both scenarios of Treasury QE, Treasury buybacks could be used as a QE-style signaling tool to further encourage investors to withdraw from money market funds (MMFs) and invest in riskier assets, thereby forcing more liquidity into the banking system.

Upon implementing Treasury QE, monetary leaders will have fitted the missing piece in their Not-QE corridor:

Treasury QE via buybacks and “Not-QE” from the Fed will provide a stronger lower bound to ease financial conditions when needed, while QT and TQT achieve the opposite effect. Moreover, if the Fed and Treasury have joint political goals, they can effectively bypass the Fed’s so-called independence, coordinating the easing and tightening of financial conditions. On the flip side, they could also offset one another’s actions. For instance, the Treasury could be “tightening” while the Fed “eases”.

For now, monetary leaders only need to activate some elements of the Not-QE corridor. U.S. Treasury officials have decided not to fire up TQT (Tighter Quantitative Tightening), while “Treasury QE” through buybacks could only come online after 2024 commences. QT (quantitative tightening) and “Not-QE”, meanwhile, remain active. QT is still shrinking the Fed’s balance sheet by $95 billion per month, whereas “Not-QE” is delivering a somewhat stimulative effect to risk assets, without the Fed ever printing reserves to buy bonds outright (actual QE).

Nobody, not even the Fed, seems to know what catalyst will cause officials to finally return to rate cuts, QE, or both. If inflation remains stickier for longer than most expect, the Not-QE corridor won’t collapse anytime soon, and monetary alchemy will prosper. The Treasury market provides those who oversee it the power to control global finance like never before. Yet they’ve chosen not to use it to its full effect. But with Treasury QE on the way, those in charge may give in to temptation. Eventually, these powers may be activated. It’s widely believed that officials are running out of ideas and tools to preserve stability. Yet in reality, the golden age of intervention is yet to come. When Treasury QE arrives, the Great Sovereign Debt Intervention™ will have only just begun.

If you enjoyed this, feel free to hit the ♡ button to let us know and share a link via social media to help us grow. Comments are also encouraged. Thanks for supporting macro journalism!

Finally an indepth, and we'll done description of how we are seeing tech hit highs after March's bank failures. Aka bank failures are bullish.

Hi conks, I know I'm late to this thread but I'm struggling to understand how this would not be yield curve control? wouldn't this qualify as YCC if it led to the suppression of yields or am I mixing this up?