The Transitory Pause

how a combination of the Fed's silence and inaction has been influencing markets

The much-anticipated liquidity drain is in motion, with many headlines predicting turbulence ahead for markets. Yet, its effects may not deliver the impact that many believe. Numerous hidden forces have emerged, acting against a liquidity squeeze. The “Transitory Pause” is here.

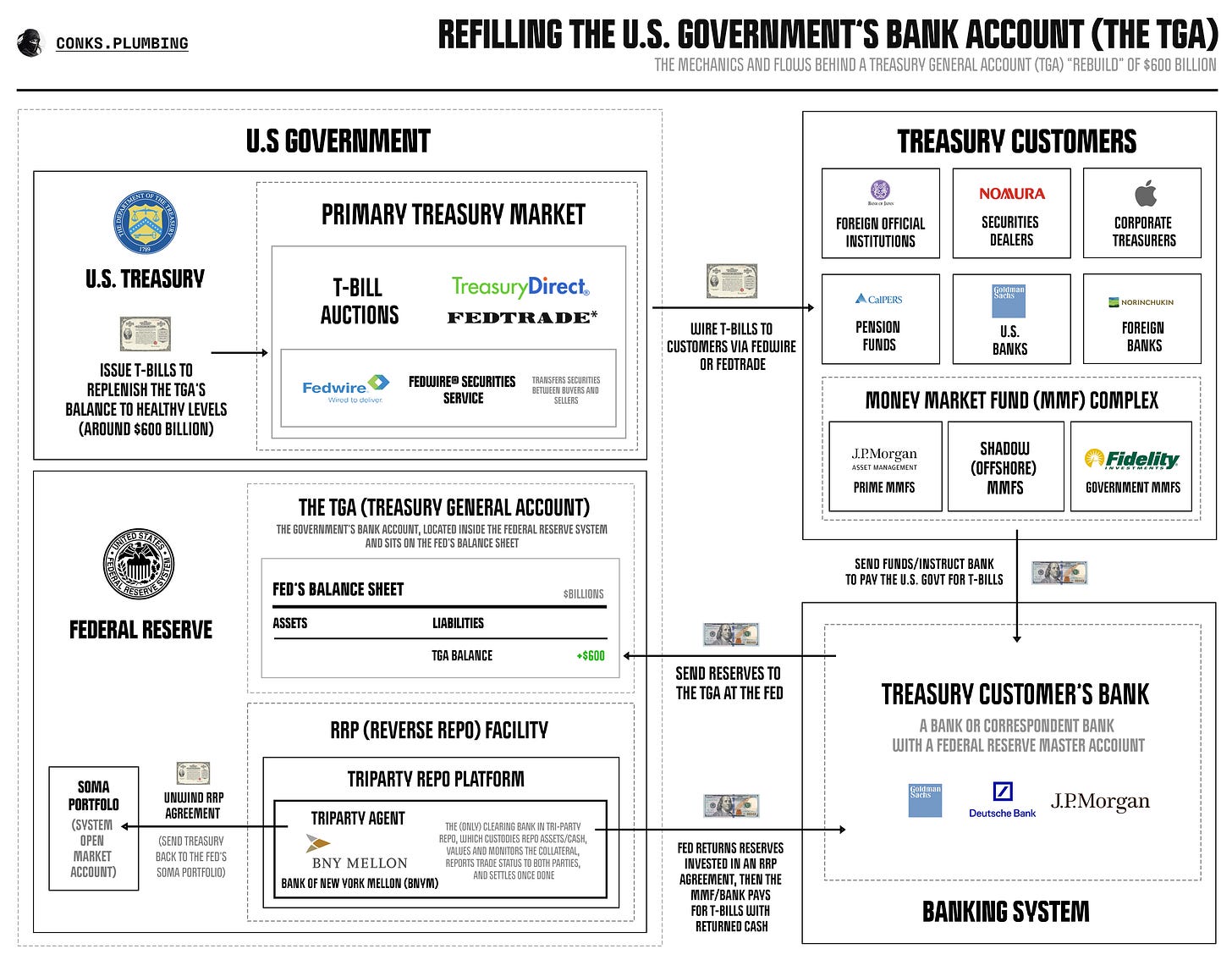

After an epic rise in stock prices in the first half of 2023, investors are wondering if the second half will produce the opposite outcome. A liquidity-fueled rally has driven the S&P500 up 12% so far this year. But now, the next significant “liquidity drain” is about to begin. The latest debt limit drama has resulted in a debt ceiling suspension till 2025, allowing monetary leaders to fire up the printing press once again. Over the remainder of 2023, the U.S. Treasury will now issue around a mammoth ~$1 trillion in t-bills — Treasuries with a one-year expiry or less — into the most systemically important market. If history repeats, officials will aim to fill the U.S. government’s bank account, the Treasury General Account (TGA) within the Federal Reserve System, with around $600 billion by September. Holding the master key to every commercial bank’s Fed account, the TGA will slowly amass reserves.

The consensus is concerned over two effects of the “TGA refill”: a large issuance of government debt prompting market instability, and the subsequent draining of bank deposits and reserves reducing liquidity. The outcomes of both, however, aren’t as scary as they appear. First, it’s believed that issuing such a large quantity of t-bills in a short space of time will be difficult for markets to absorb, blowing out spreads and provoking turmoil. But as history shows, bond markets absorb huge issuances, even within a month, without much hassle.

As for demand, with yields offering the highest return in decades, plus the switch from an unsecured (LIBOR) to a secured (SOFR) monetary standard in full swing, the world is eager to chomp on America’s ever-increasing debt load. Financial behemoths are hungrier than ever. We also know in advance that major market players are willing to consume a large batch of sovereign debt by referring to the Treasury’s latest survey of the Fed’s “primary dealers”, specific entities the central bank mandates to make markets in Treasuries. Expectations are in line with demand.

Instead, it’s not whether market participants will be able to absorb trillions in new issuance but who buys the majority of Treasuries issued that will influence markets. The real concern is the subsequent liquidity drain from the banking system. Will this prompt another liquidity squeeze? It’s not as clear-cut.