The Great Financial Tightening

the latest market mania has set the stage for more intervention by monetary powers

After the most euphoric January in recent history, hopes of a new bull market have emerged in spectacular fashion. Yet the latest stock market bonanza has set the stage for increased intervention from monetary leaders. The Great Financial Tightening™ is about to commence.

Following a subpar end to 2022 for risk assets, where tax-loss selling and declining economic data fueled a sharp market selloff, the start to 2023 couldn’t be more different. Buoyant economic data, enormous liquidity injections, and bullish narratives drove an epic meltup. This sudden shift in sentiment caused a market positioned for an imminent recession to be caught off guard, creating the false appearance of rampant euphoria. The worst quality stocks, from bankrupt companies to those with dubious business models, defied reality and skyrocketed.

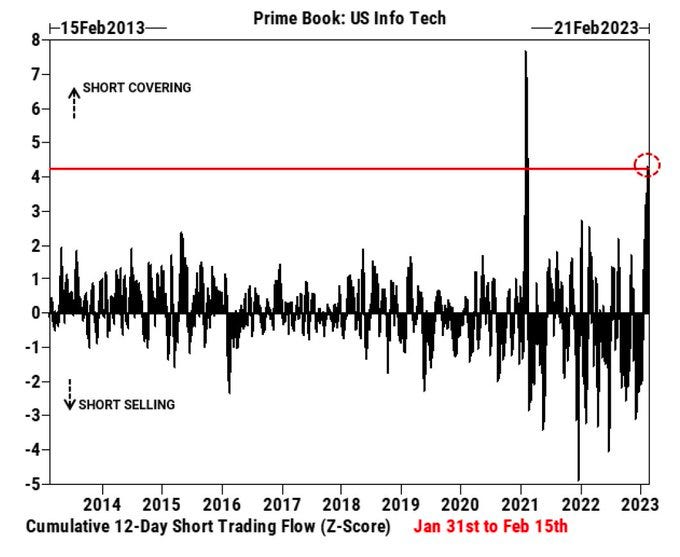

This set the scene for one of the greatest short squeezes in stock market history, which only exacerbated the market rally. Not only did shorts cover en masse, but the act of doing so (buying back shares and paying off a loan) added more liquidity to further fuel the meltup.

The fear of missing out then spread like wildfire. Money managers who were squeezed at the bottom started chasing the top. Others either caught off guard or were simply underweight stocks going into 2023 turned bullish and joined in. But this was only the start.

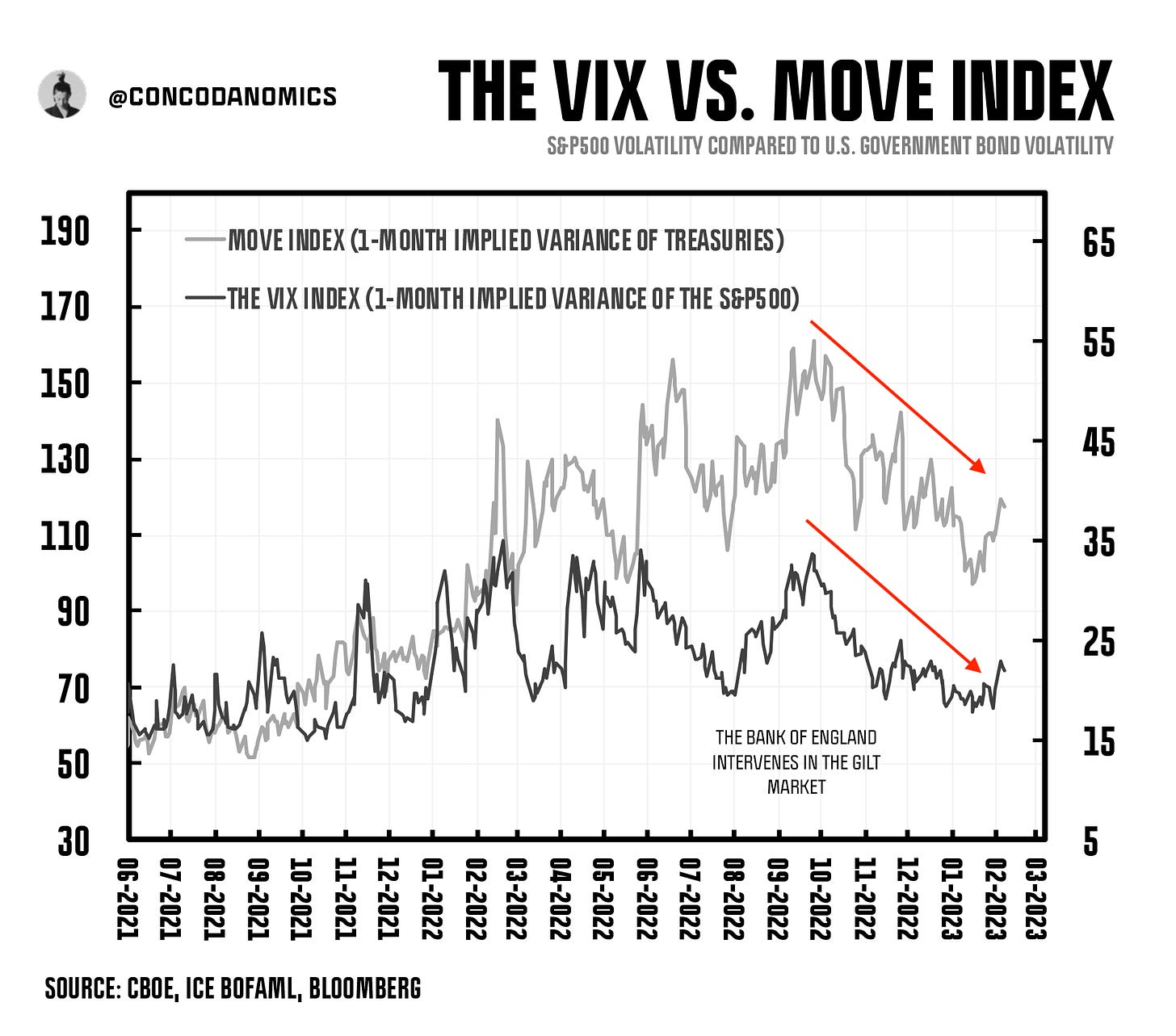

The magnitude of the rally triggered buying from the rising number of market entities, both machine and human, who bid up stocks regardless of price or fundamentals. The decreased levels of volatility in bonds and stocks created an additional self-fulfilling loop of buying. A plunge in the U.S. 10-year yield (from 3.9% to 3.3%) caused target-date funds to rebalance from bonds into stocks, the opposite of when bond yields were rising. Meanwhile, volatility-control funds, which purchase more shares simply because volatility decreases, kept buying.

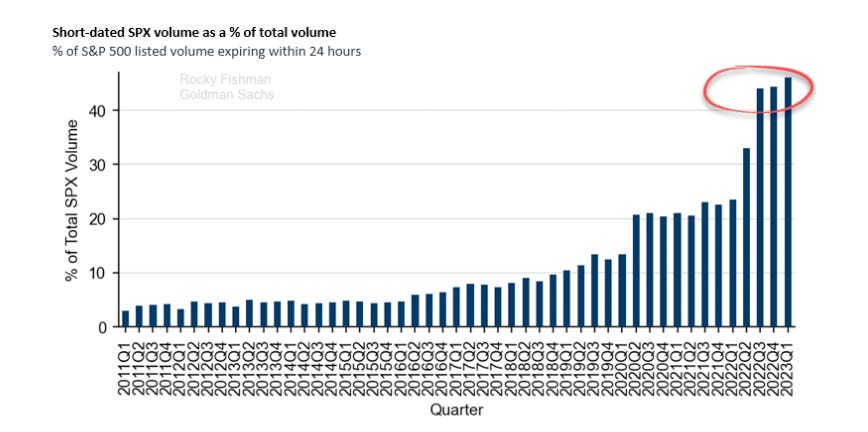

This loop of volatility suppression only enabled the “smart money” to exacerbate the meltup. Through ultra-short-term options known as 0DTE, market makers could supply enormous amounts of liquidity to the options market, where the vast majority of trading now occurs.

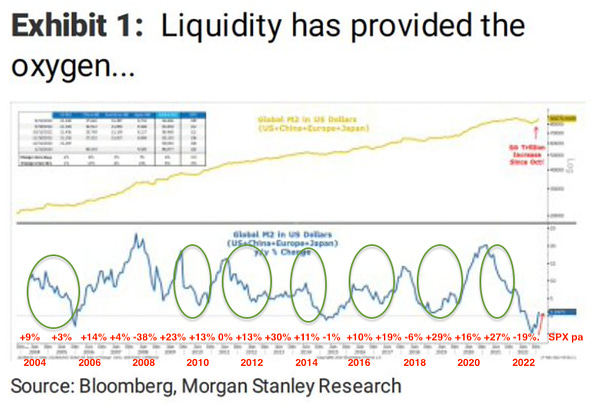

Throughout all this, numerous narratives emerged to explain the stock market euphoria, likely assisting the rally further, from the U.S Treasury spending down its bank account (the TGA) and pushing liquidity into the system to China and Japan injecting large amounts of stimulus. By late January, whatever was used to justify a rise in stock prices didn’t need to be true to pump markets. If everyone believed, it was accepted despite its validity. For instance, it’s well known that sharp market rallies occur even during rapid drops in “liquidity”.

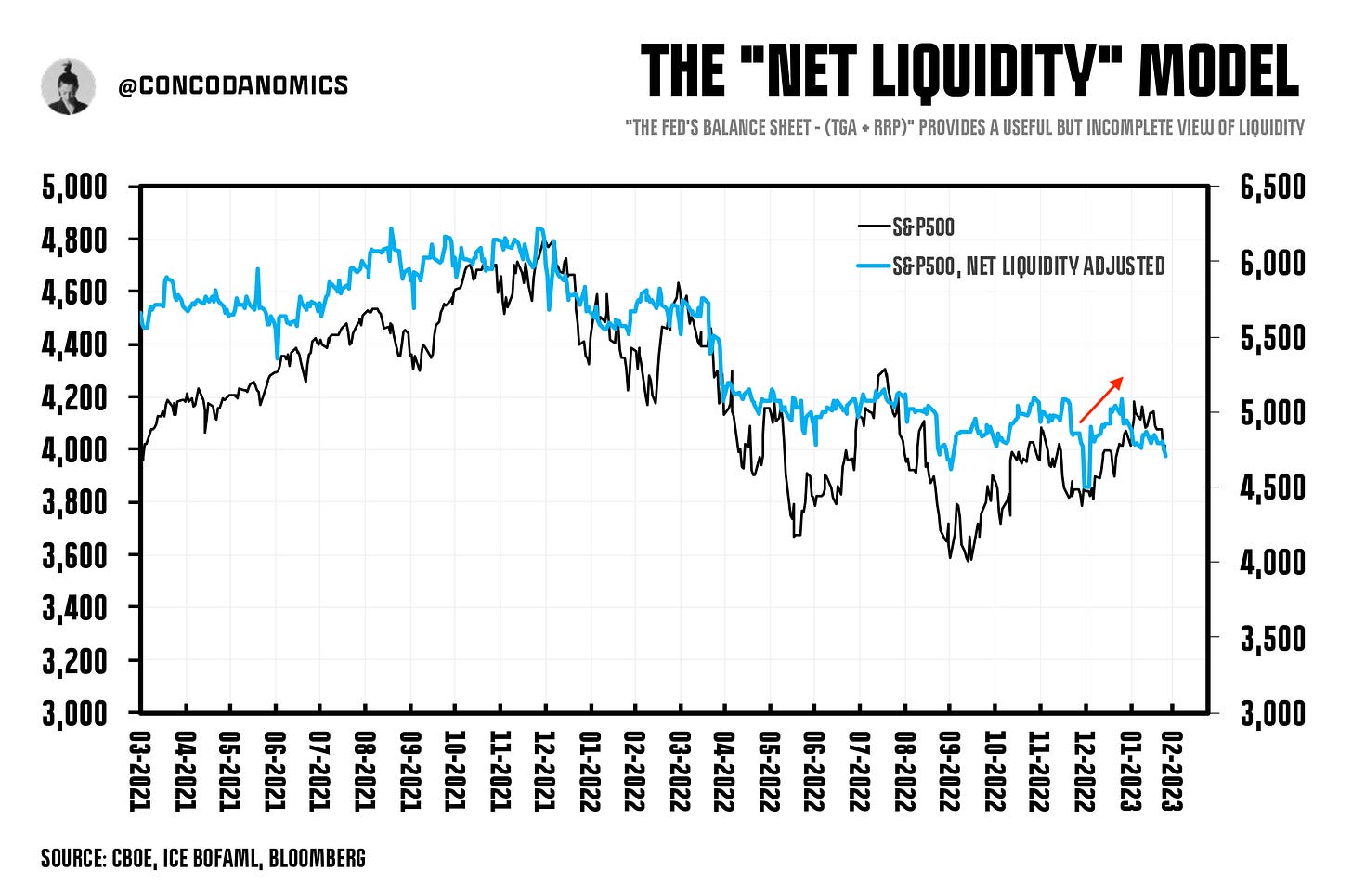

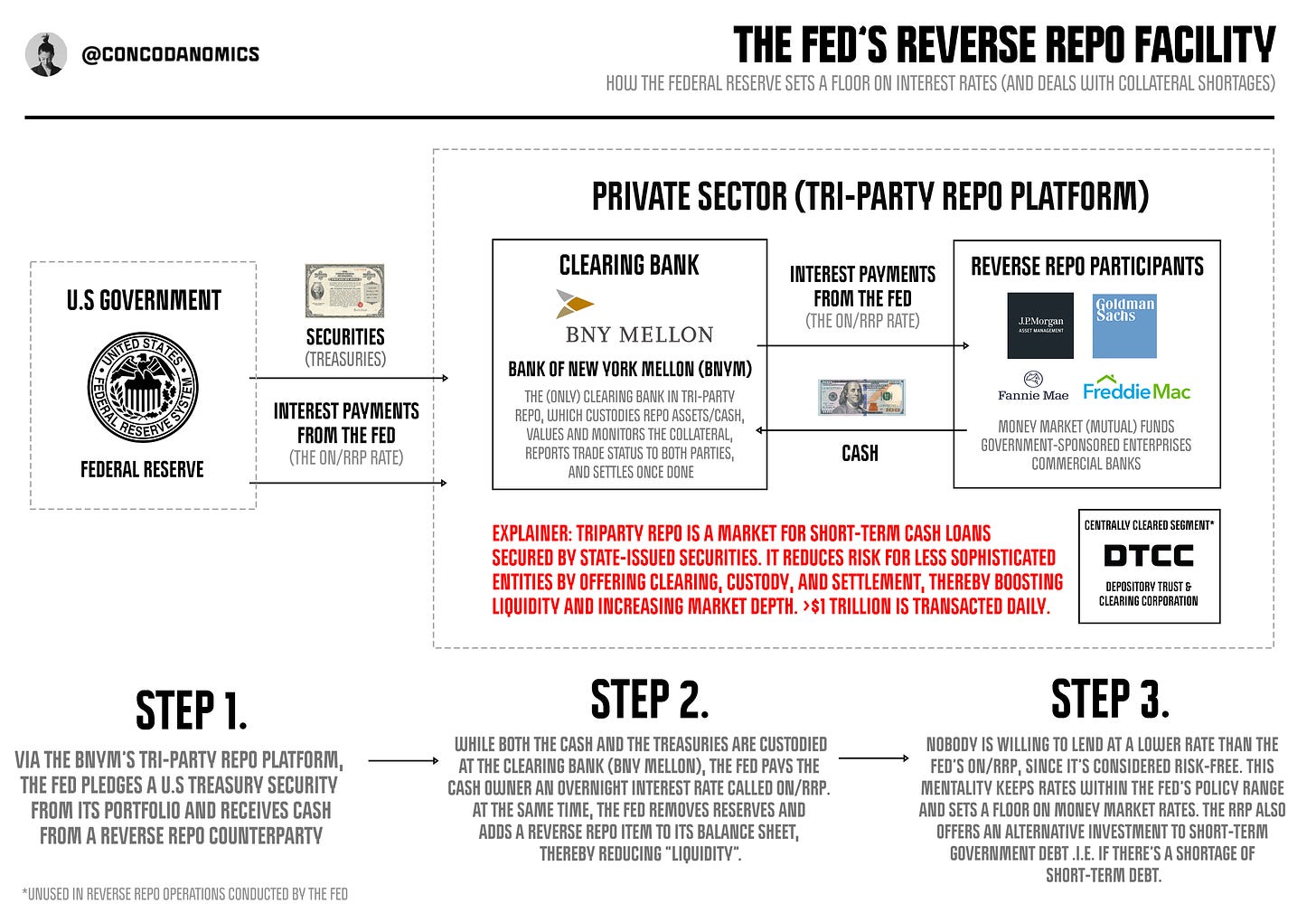

The most popular narrative was that the rally had been fueled by a rapid rise in so-called “net liquidity”. This takes the dollar value of the Fed’s balance sheet and subtracts money held in the TGA (the U.S. government’s bank account) and the Fed’s Reserve Repo Facility (RRP).

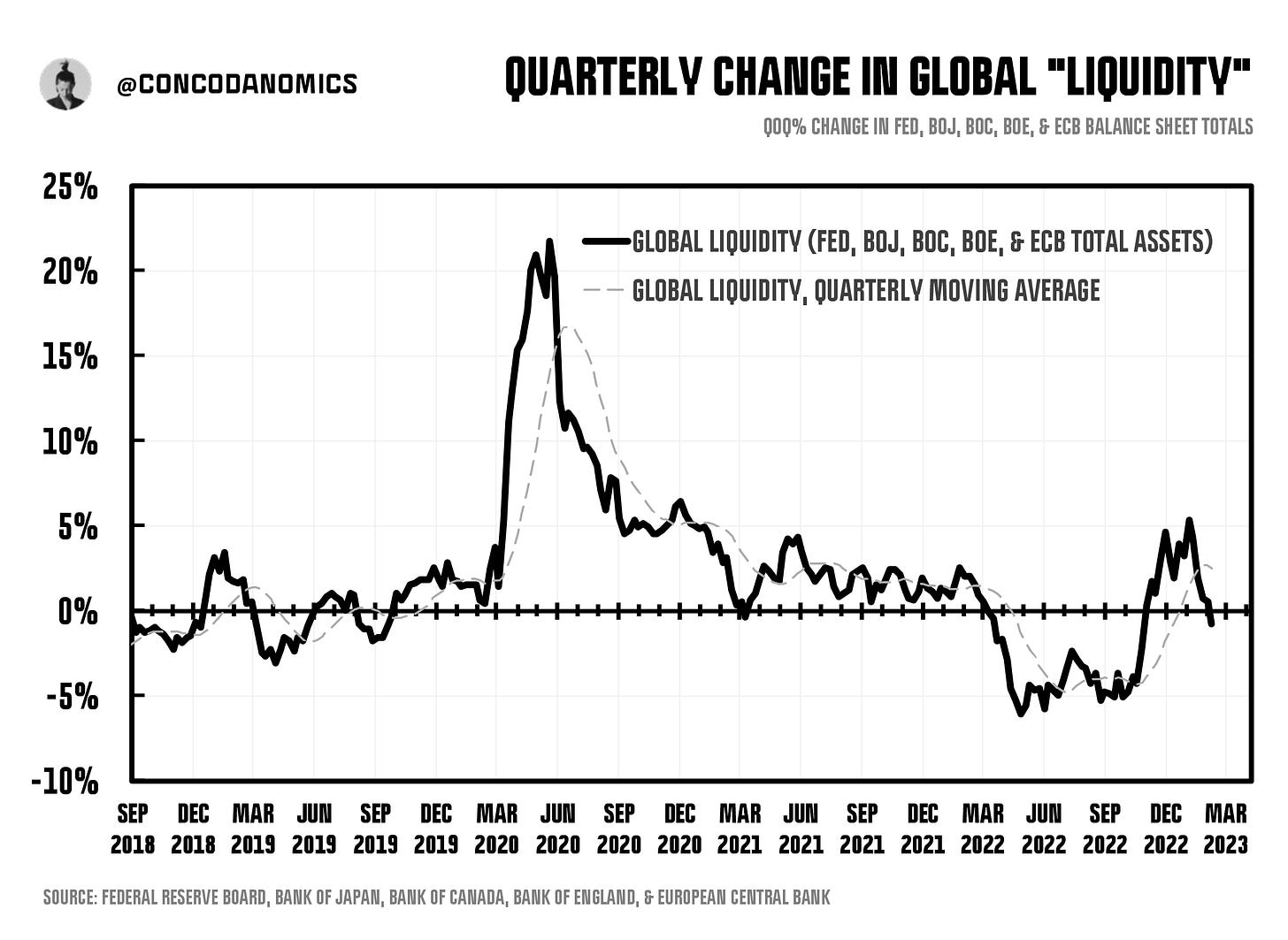

Though the net liquidity model is somewhat useful, it’s far too narrow a measure, overlooking multiple parts of the liquidity picture. In fact, despite showing a solid connection between stock prices and liquidity, it likely understated the level of euphoria playing out in real-time. Not only did the net liquidity model provide an incomplete picture, but so did the popular measure of “global liquidity”. Adding together the total assets of major central banks ignores extensive parts of the global liquidity machine.

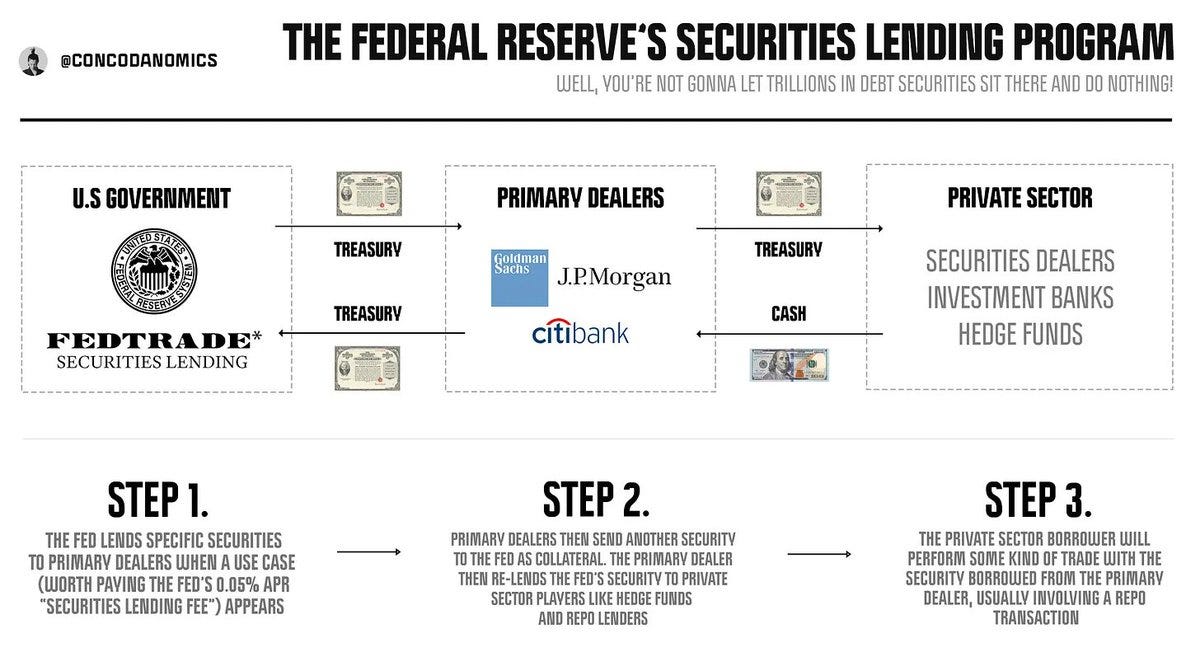

For starters, the Fed can provide financial behemoths with billions, if not trillions, of liquidity via its securities lending program, regardless of changes in its balance sheet’s size. Banks can borrow the Fed’s assets to fuel more credit creation, hence more “liquidity”.

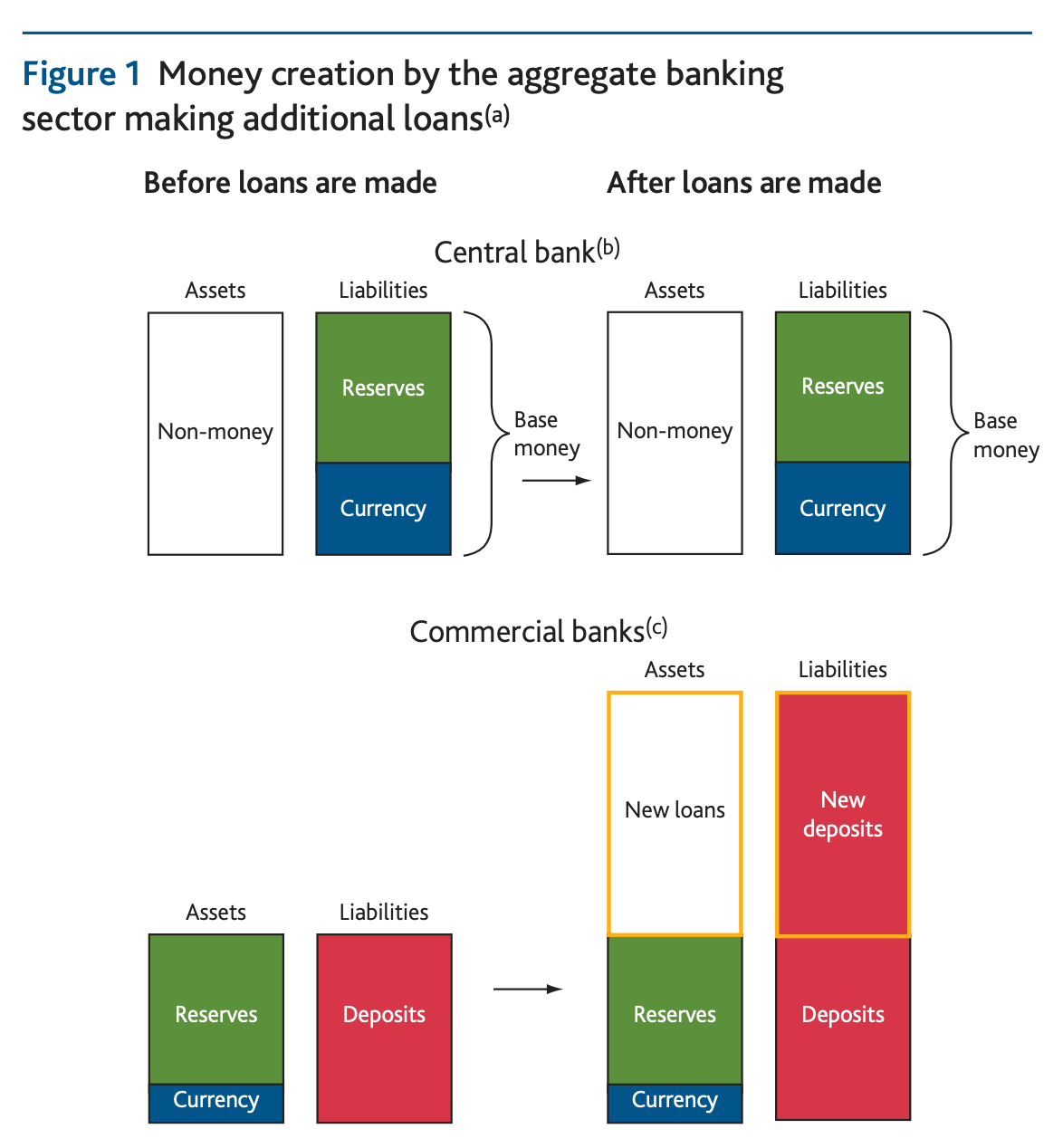

What's more, banks themselves are the only entities other than the U.S. government with the license and ability to create U.S. dollars “out of thin air”. If a consumer is deemed reliable, banks expand the money supply (within regulatory limits), juicing liquidity further. Liquidity will be injected if animal spirits remain high and will occur without the U.S. government or the Federal Reserve ever getting involved. Despite changes in “net liquidity”, banks are free to expand their balance sheet and create money for the masses out of thin air.

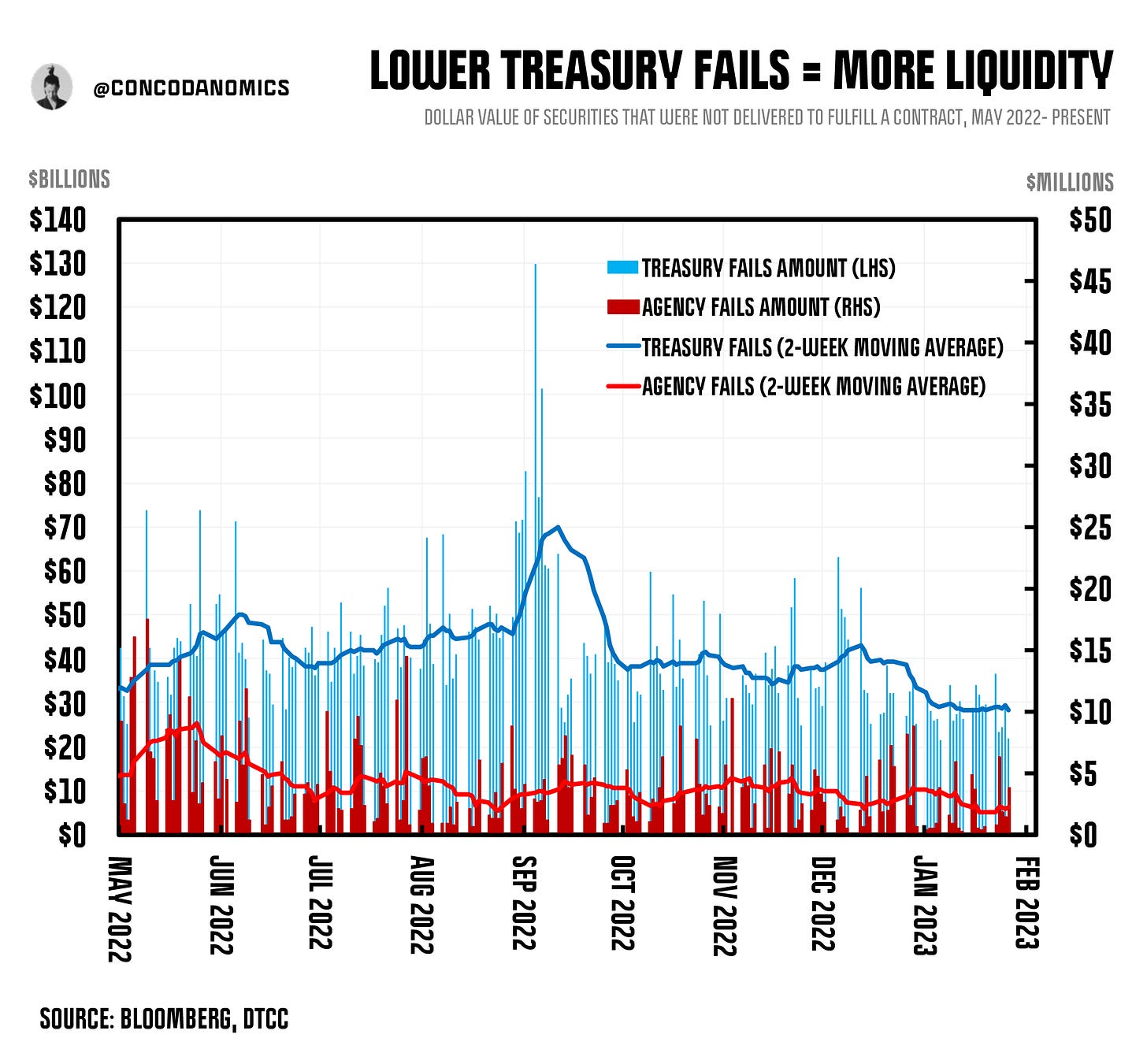

Lately, this is exactly what has played out. The amount of consumer and commercial loans has boomed, while “Treasury fails” (daisy chains of collateral breaking apart) have reached a recent low. Even deep in the monetary system, liquidity remains abundant for now.

The subsequent fall in bond volatility has also greased the pipes in the monetary plumbing, helping to fuel ample financing in key funding markets. Thus the MOVE index, which has recently become the most popular measure of Treasury volatility, has dropped significantly.

It’s been declining since political turmoil erupted in Britain, sparked by former Prime Minister Liz Truss’s ill-received budget. The Bank of England (BOE) had to intervene in the U.K. bond market to avert a sovereign debt crisis, initiating a major shift in sentiment. The BOE’s intervention not only prevented contagion from spreading overseas but reduced bond market volatility worldwide. Markets started to believe central banks were willing to adopt a soft version of QE. From then on, both stock and bond volatility declined.

Fast forward to today, and that impulse has become a major driver of the latest market euphoria. But recent events and data now show that the party is over. Any hopes of QE (Quantitative Easing) or interest rate cuts have been dashed dramatically. Hawkish data, from the PPI to the CPI to the labor market, plus the Fed’s latest remarks, suggest further destruction of risk sentiment will be enacted to reach the Fed’s 2% target, a goal that many believe to be rather optimistic.

Rare mishaps like Fed Chair Jerome Powell giving the green light to stocks (by suggesting financial conditions haven’t eased) won’t be repeated. Instead, the Fed will soon double down, initiating the Great Financial Tightening™.

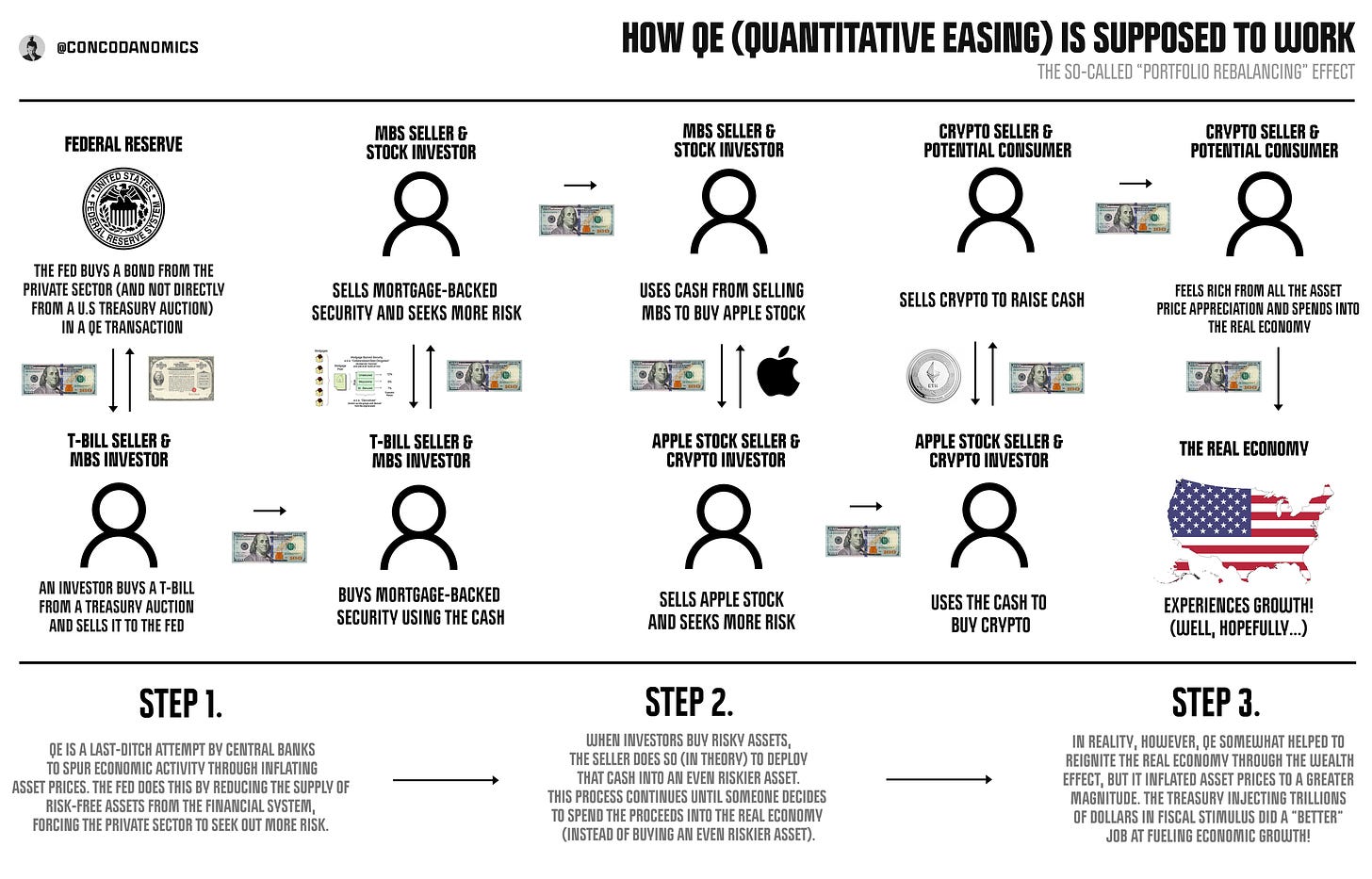

To curb the inflation monster that is the U.S. economy, the Fed’s future actions will need to be increasingly tighter. Especially after one of its primary tools has grown almost ineffective: QT (quantitative tightening).

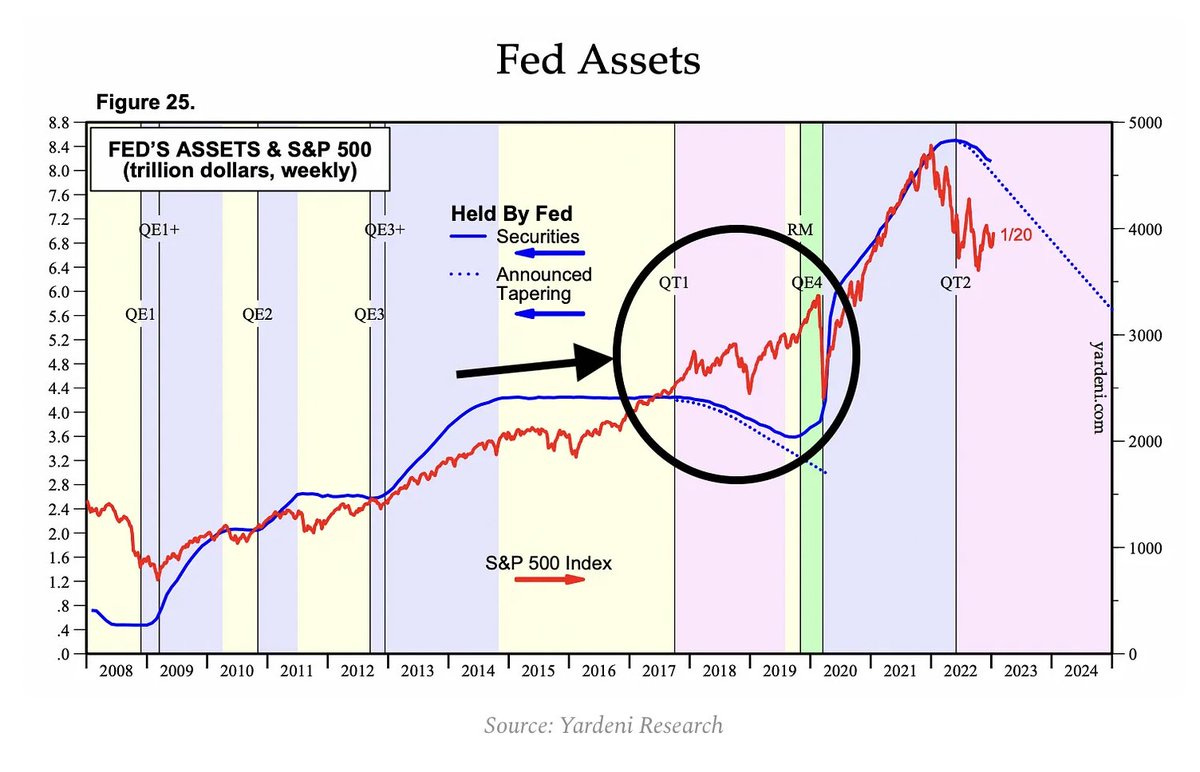

Like how QE failed to spur ample economic growth while juicing risk assets, QT has proven just as futile in achieving its original goals. The market is finding it easy to pay off $60 billion a month in maturing bonds from the Fed’s balance sheet. “Tightening” is an overstatement.

Based on past episodes, it’s not a revelation that QT’s tightening powers have been exaggerated. During the first official QT from October 2017 to Late 2019, risk assets rallied, despite the Fed selling $675 billion in Treasuries and MBS securities...

Today, it’s not just the finance world starting to accept that QT, like QE, isn’t achieving what its name suggests. QT is once again barely affecting financial conditions, which even Fed officials themselves have begun to admit. In a recent interview, Fed Governor Waller revealed the Fed could count the $2.1 trillion in the Fed’s reverse repo facility (RRP) as part of total reserves. This suggests the Fed may enact “QT infinity”, leaving QT on autopilot longer than anticipated.

Given QT is supposed to tighten financial conditions, the idea of “QT Infinity” paints a long-term picture of liquidity being drained from the system. But as it stands, the reality is quite the opposite. This, however, is about to change.

If QT is going to help achieve a 2% inflation target, the Fed will be forced to boost QT’s effectiveness. Yet in the latest FOMC minutes, officials appear to still be asleep. All supported further shrinkage of the Fed’s balance sheet but nobody hinted at increasing QT’s “run-off”, the number of bonds that will mature off its balance sheet monthly. If so, the Fed will compel the private sector to shrink its asset portfolio at a greater pace.

Still, this will likely fail to deter risk sentiment meaningfully. A key modification is needed. With the U.S. Treasury continuing to issue more short-term debt, financial entities aren’t going to ditch risky assets to fund the U.S. government’s obligations. Since short-term Treasuries like T-Bills remain risk-free, the private sector will absorb the debt but without selling riskier assets to fund these purchases. Longer-term Treasuries (Bonds or Notes), however, are sensitive to large interest rate changes. They bear extra risk.

Therein lies the potential for QT. If monetary leaders need a tool to dampen risk sentiment further, the Fed alongside the U.S. Treasury could embark on what Conks calls “TQT”: Tighter Quantitative Tightening.

Alongside the Fed shrinking its balance sheet faster, the U.S. Treasury could start issuing more long-term debt. Investors will have to take on increased duration risk via longer maturities. The higher the duration, the greater the losses when interest rates skyrocket. As bond yields have fallen somewhat since the BOE intervention, this provides officials with some leeway to issue a riskier supply to the market. Investors will, as the Fed hopes, absorb higher doses of duration risk and fund those purchases by selling riskier assets.

Right now, after a string of bullish data and Fed remarks, the recent disinflationary narrative has come to an abrupt halt. The stage is now set for the Great Financial Tightening™ and possibly even TQT. Markets have begun to price in a “higher for longer” scenario.

Monetary leaders will thus be compelled (reluctantly) to reintroduce volatility into markets, which will once again become the major driver of asset prices. Soon, all entities that benefited and adapted to lower volatility will have to readjust to heightened market uncertainty. Sentiment will slowly shift from euphoria back to the old status quo: a slow grind down in risk assets, while volatility remains elevated but contained.

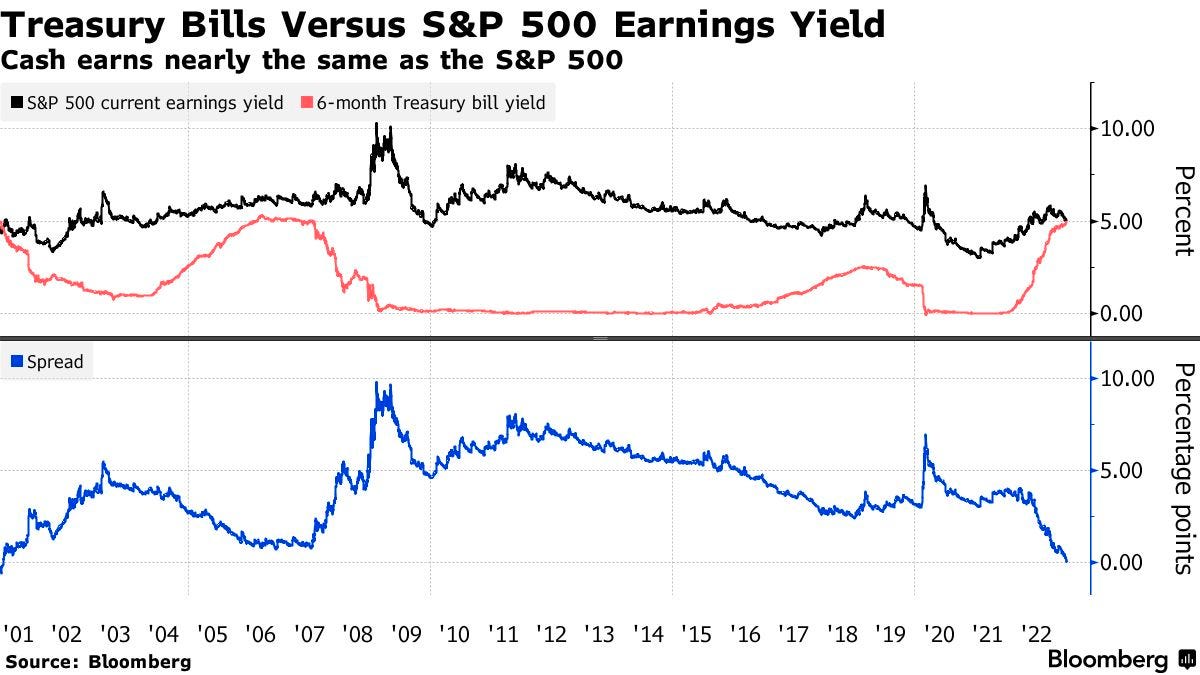

Those that bought risk assets solely because volatility and yields were tumbling will have to rebalance once again. As yields move higher, target-date funds must sell stocks to buy bonds. Volatility-control funds will reduce their exposure as equity vol rises. Money managers who chased the rally might think twice, while market makers try to operate in disorderly conditions. Moreover, leading economic indicators will continue to point to lackluster growth, causing investors to deem cash as king. After all, the S&P500 earnings yield already pays the same as Treasury bills, while money market funds (MMFs) earn investors a 4% risk-free return.

Today, we’re already witnessing the early innings of the Great Financial Tightening™. Rates and volatility markets are starting to price in higher for longer. Financial conditions indices are beginning to turn sour. And leading indicators are starting to matter. The disconnect between fundamentals and markets has yet to fully converge, but the Great Financial Tightening™ will bring an end to the latest liquidity splurge. Goldilocks is almost over. Now it’s time for volatility to make an unwelcome return.

If you enjoyed this, feel free to smash that like button and share a link via social media. Thanks for supporting macro journalism!

"The "smart money" is now exploiting a new regulatory loophole in the options market to make a quick (lucrative) buck. They are selling large amounts of deep out-of-the-money 0DTE options, without having to post margin to clearinghouses, who don't count intraday expiries.." My question: if margins aren't needed to be posted, doesn't this allow extra 'money' (liquidity) to flow into the system, just like derivatives increased money supply in the economy in the Great Financial Crisis?

"For starters, the Fed can provide financial behemoths with billions, if not trillions, of liquidity via its securities lending program, regardless of changes in its balance sheet’s size. Banks can borrow the Fed’s assets to fuel more credit creation, hence more “liquidity”."

Isn't this liquidity draining? The non-banking sector gives the banks cash in exchange for Treasury or whatever they pledge as collateral.