The Fed's Repo Defensive: Part I

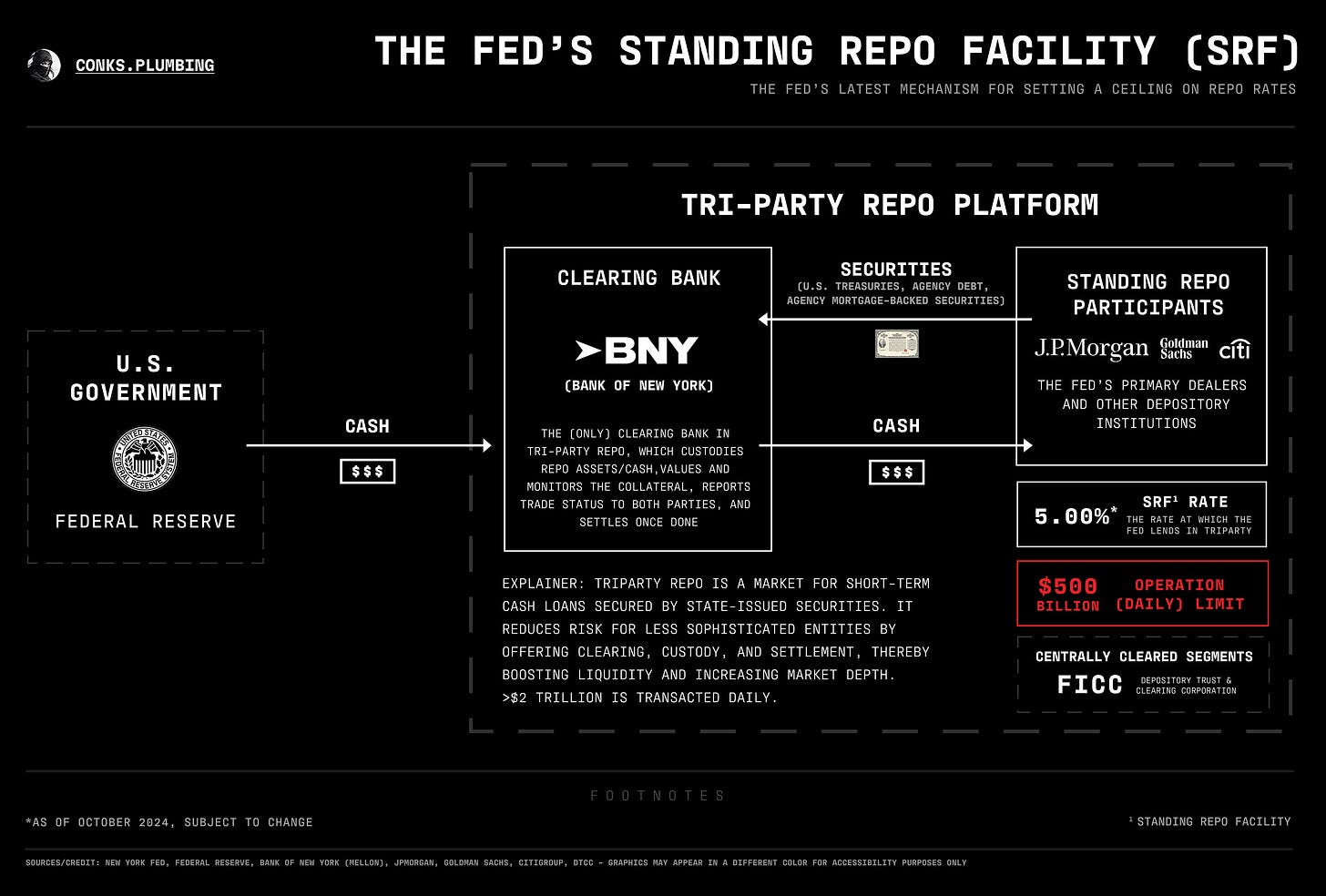

the U.S. central bank's emergency repo facility is set to evolve

For the first time, more than three years after becoming an official installation, the Fed’s SRF (standing repo facility) has been tapped — for its true purpose — by major market makers. A stormy quarter-end1 forced hundreds of billions of dollars in repos to trade above the Fed’s target range, causing primary dealers to borrow from the central bank’s cheaper alternative. Even so, dealers only tapped a fraction of overall volumes via the SRF. This not only prevented the Fed from enforcing a “hard ceiling” on rates2 but exposed notable flaws in its defense mechanism, which may fail to prevent turmoil from spreading in the next repo upheaval. With market pressures building and liquidity draining, the U.S. central bank is thus set to reinforce its SRF and attempt to deter spillovers3 into FX swaps and the interbank4 market. The Fed’s “Repo Defensive” is looming.

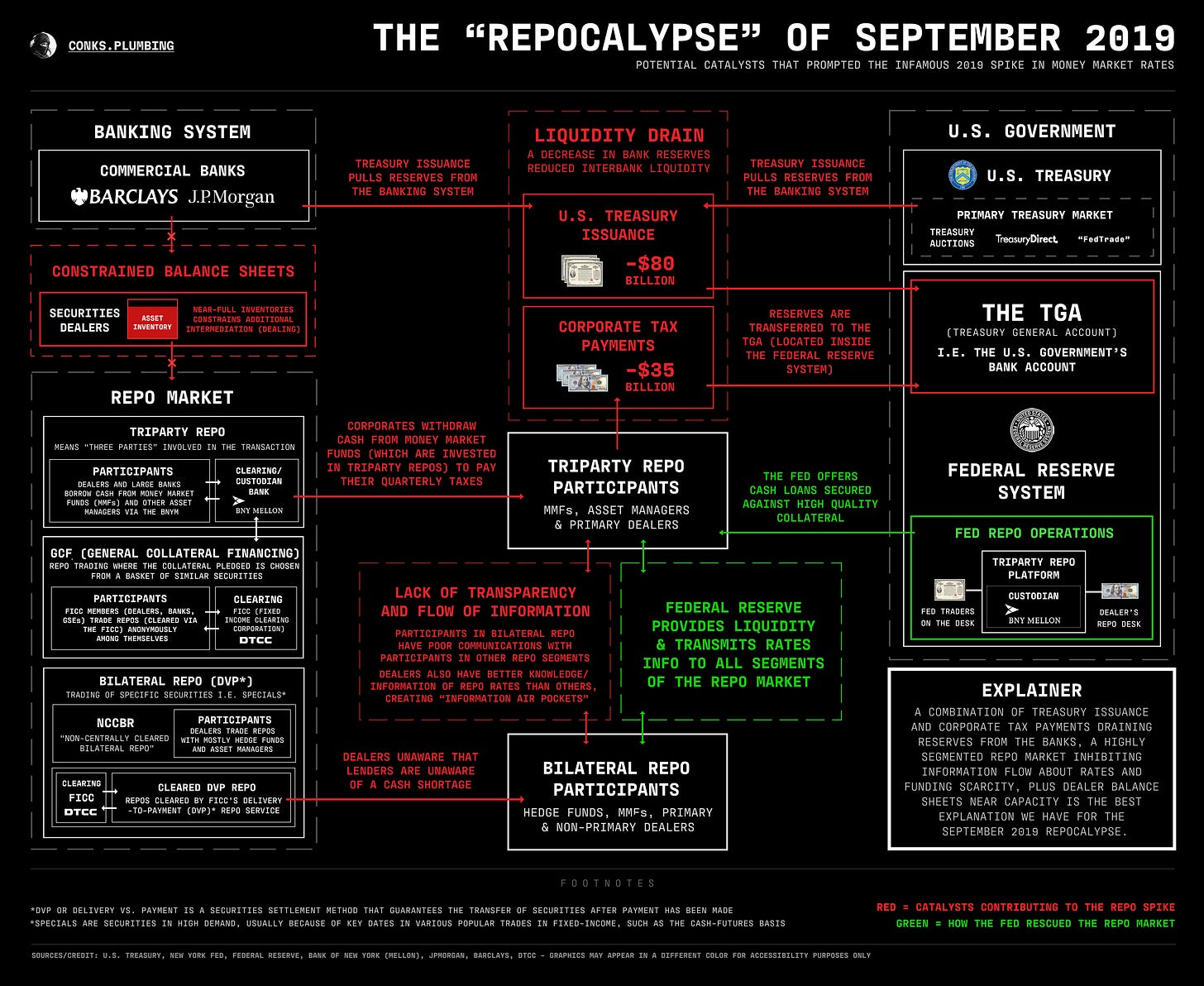

Seven years ago, aiming to reduce its supposedly mammoth balance sheet, the Fed launched its first official QT5 (quantitative tightening) operation. Two years of balance sheet runoff (i.e. reduction) later, the U.S. central bank decreased reserve balances from $2.5 trillion to a mere $1.3 trillion. Interbank liquidity began hovering at unstable levels. Then, on September 17th, 2019, money market rates in repo, FX swaps, and Fed Funds skyrocketed, all blowing through the top of the Fed’s target range — i.e. its upper jaws. The “repocalypse” of 2019 had arisen.

As panic circulated, some repo trades captured by SOFR, the Fed’s secured lending benchmark, reached almost four times the Fed’s upper jaws of 2.25%, while EFFR, the U.S. central bank’s official policy rate, poked through narrowly. Liquidity grew so scarce that banks and dealers scrambled for cash in various opaque markets. First, U.S. dollars dried up in repo, then the FX swap market — repo’s closest alternative, forcing large banks to turn to their funding market of last resort: Fed Funds (i.e. the market for bank reserves). These prominent market makers bid for overnight Fed Funds (o/n FF) and lent reserves into other money markets, profiting from much wider cross-market spreads6. Regardless, extreme imbalances in money markets persisted, which not even JPMorgan — the private lender of last resort — or the FHLBs (Federal Home Loan Banks) — the public lender of first resort — could counteract. Only a public lender (and soon-to-be dealer) of last resort, with the sole power to create interbank liquidity, could bring money market rates back into balance.

As Fed Funds (EFFR) soon breached the upper limit of the Fed’s target range, a mammoth intervention was inevitable. Central bank architects were about to unveil their latest round of monetary alchemy, turning the Fed into not only a lender but a dealer of last resort.