— click here for The Fed’s Global Put: Part I

A cluster of rules forcing banking giants to stockpile liquidity, paired with the Fed’s QT1 (quantitative tightening), has restricted the private lenders of last resort from policing the top of the dollar rates hierarchy. On its own, this may not force the Fed to cease its most extensive balance sheet reduction (i.e. taper) on record. Yet, a medley of incoming catalysts could prompt reserves to once again fall to unstable levels, which central bank models may fail to anticipate. With a series of liquidity blindspots ahead, the Fed will soon exercise2 its next “plumbing put.”

Halfway through 2017, alongside the undead Fed Funds market, a parallel interbank ecosystem began to emerge. Fed officials had forced global systemically important banks, known as G-SIBs3, and other large systemic players to protect the banking system from their own demise. These financial behemoths began submitting what the Fed called “living wills,” resolution plans to allow officials to quietly wind down failed banks’ operations while avoiding another Great Financial Crisis (GFC). A post-crisis attempt by Fed architects to eradicate “too big to fail” megabanks had been initiated.

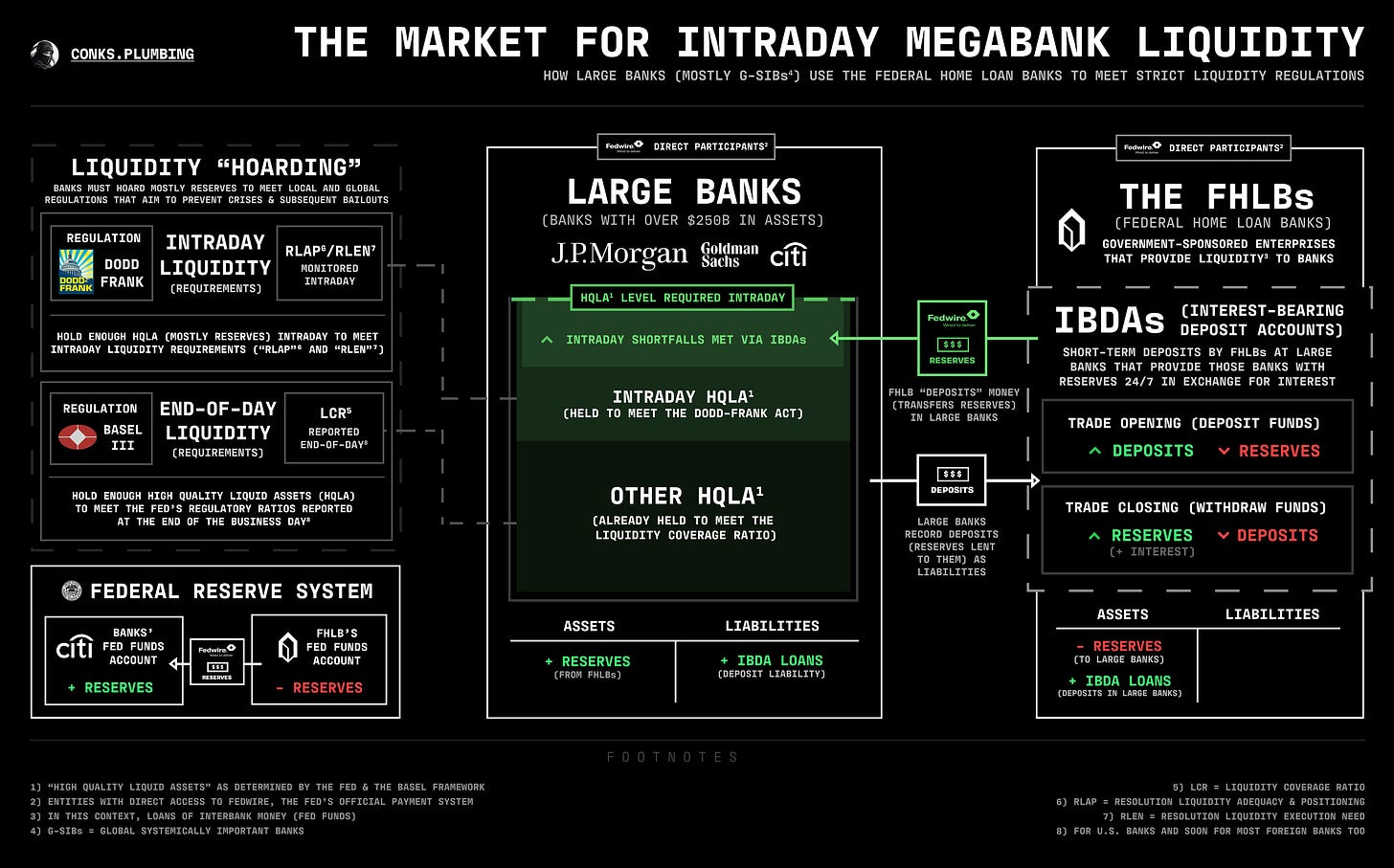

Subsequently, out of numerous constraints that followed, the Fed ordered the largest Wall Street banks to maintain not only adequate end-of-day liquidity — to satisfy Basel III — but also “resolution liquidity,” a sufficient intraday cushion, to fulfill new regulations4. Every one of a bank’s entities had to maintain an around-the-clock buffer of high-quality liquid assets (HQLA)5. Drop below at any time and face the wrath of the regulator. By mid-2017, the U.S. central bank’s rules had grown even more ruthless, so much so it was time for Basel III to step aside as the primary constraint on banking giants. With the Fed’s living wills acting as extra shackles, a market for intraday megabank liquidity was set to emerge.