The Fed's Global Dilemma

The U.S central bank's primary mechanism has an inconvenient weakness

The banking panic is almost over, yet the Fed has already resumed the Great Financial Tightening. This will not only induce another inevitable breakage and subsequent rescue but boost the U.S. central bank’s global presence. The Jaws of the Fed™ are about to be unleashed.

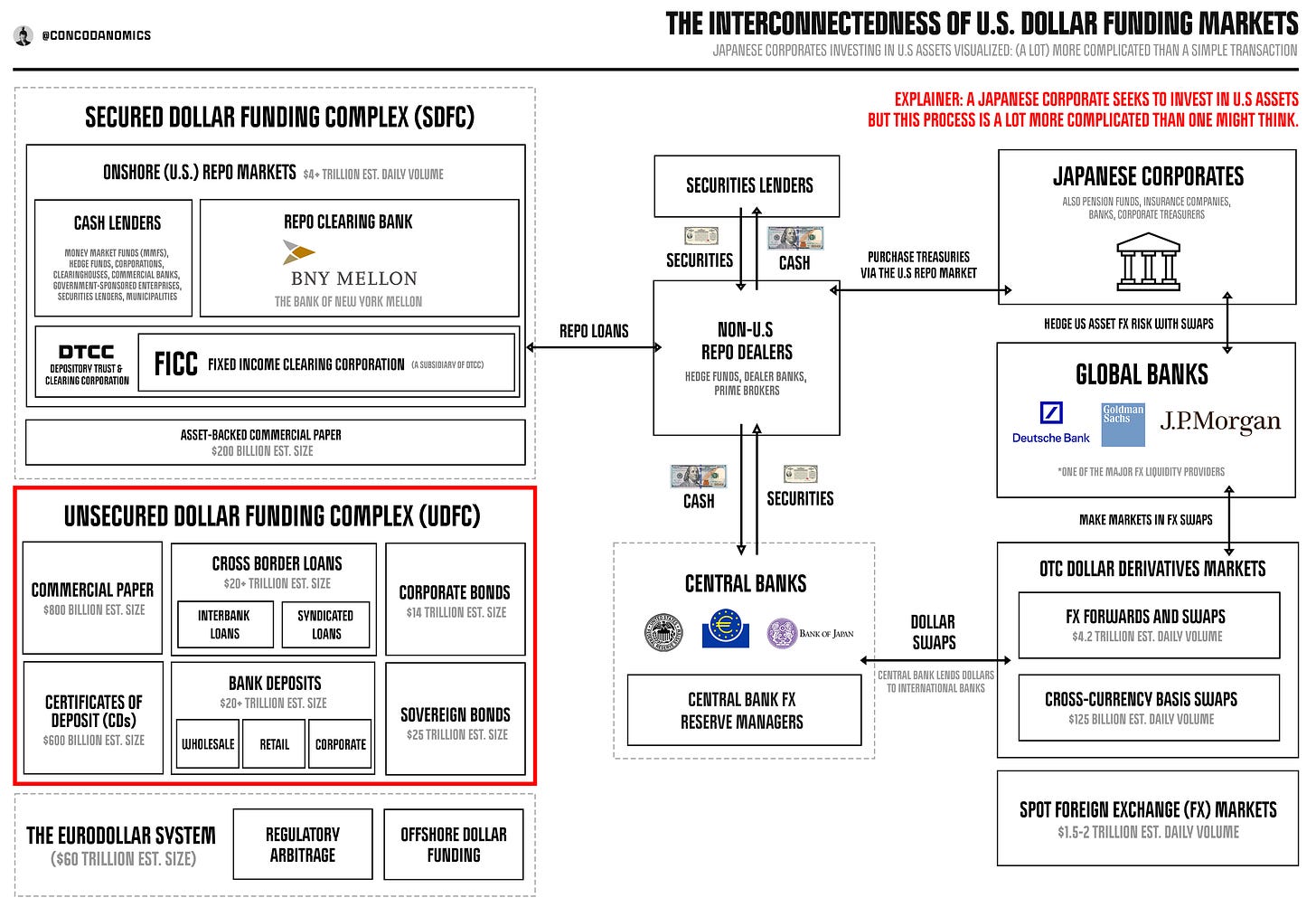

The GFC (Great Financial Crisis) of 2007/08 transformed the global monetary system forever. Monetary leaders, along with financial giants, sculpted a new paradigm in which the U.S. empire would absorb any systemic risk, especially when it threatened the status quo. The bank bailouts marked the start of a shift from an “unsecured” to a “secured” monetary standard. The mighty Unsecured Dollar Funding Complex (UDFC), where banks and global firms financed their operations by lending among themselves, was about to lose its supremacy.

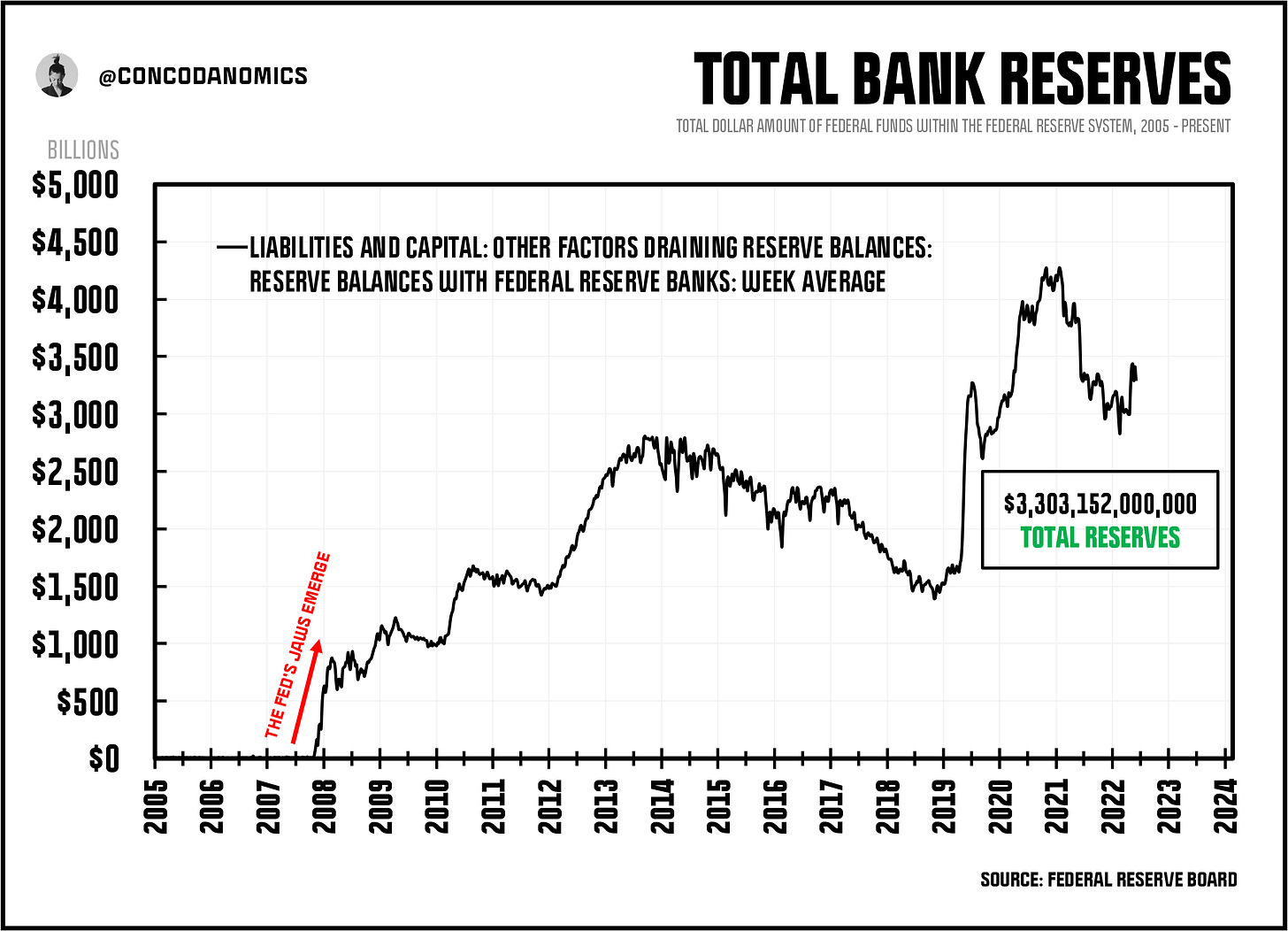

After a large-scale effort by the Fed to reboot the global financial machine, the UDFC was doomed. Central bank officials flooded the interbank system with trillions in “bank reserves”, currency used only by banks to settle payments. The “excess” reserves era of financial markets had begun.

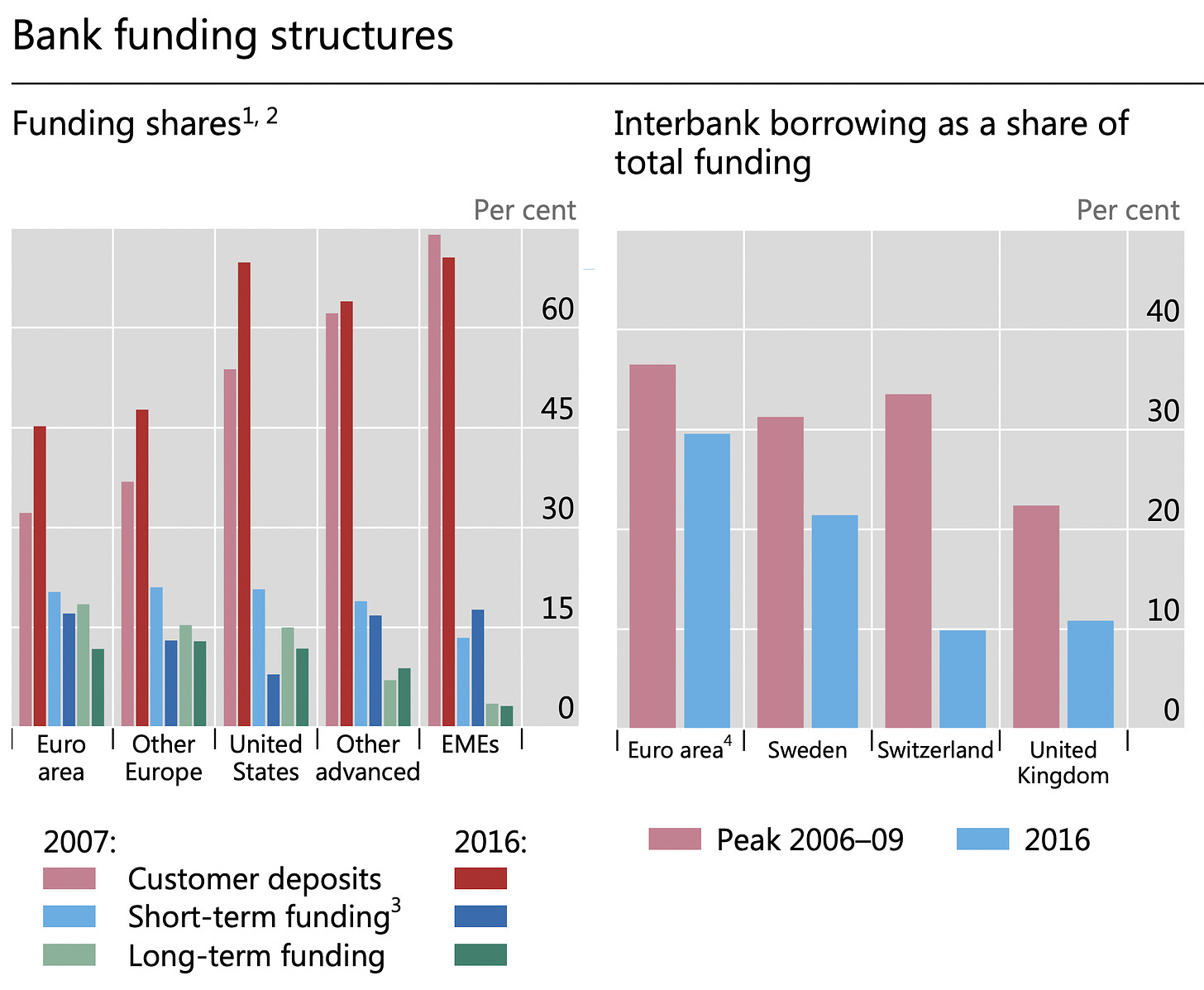

Slowly but surely, as more reserves saturated the system, the Secured Dollar Funding Complex (SDFC) took over. Regulators decided banks must fund themselves without relying on one other, which meant lending from shadow banks in the repo market while attracting a larger amount of retail deposits — the cheapest, most regulatory-friendly source of funding.

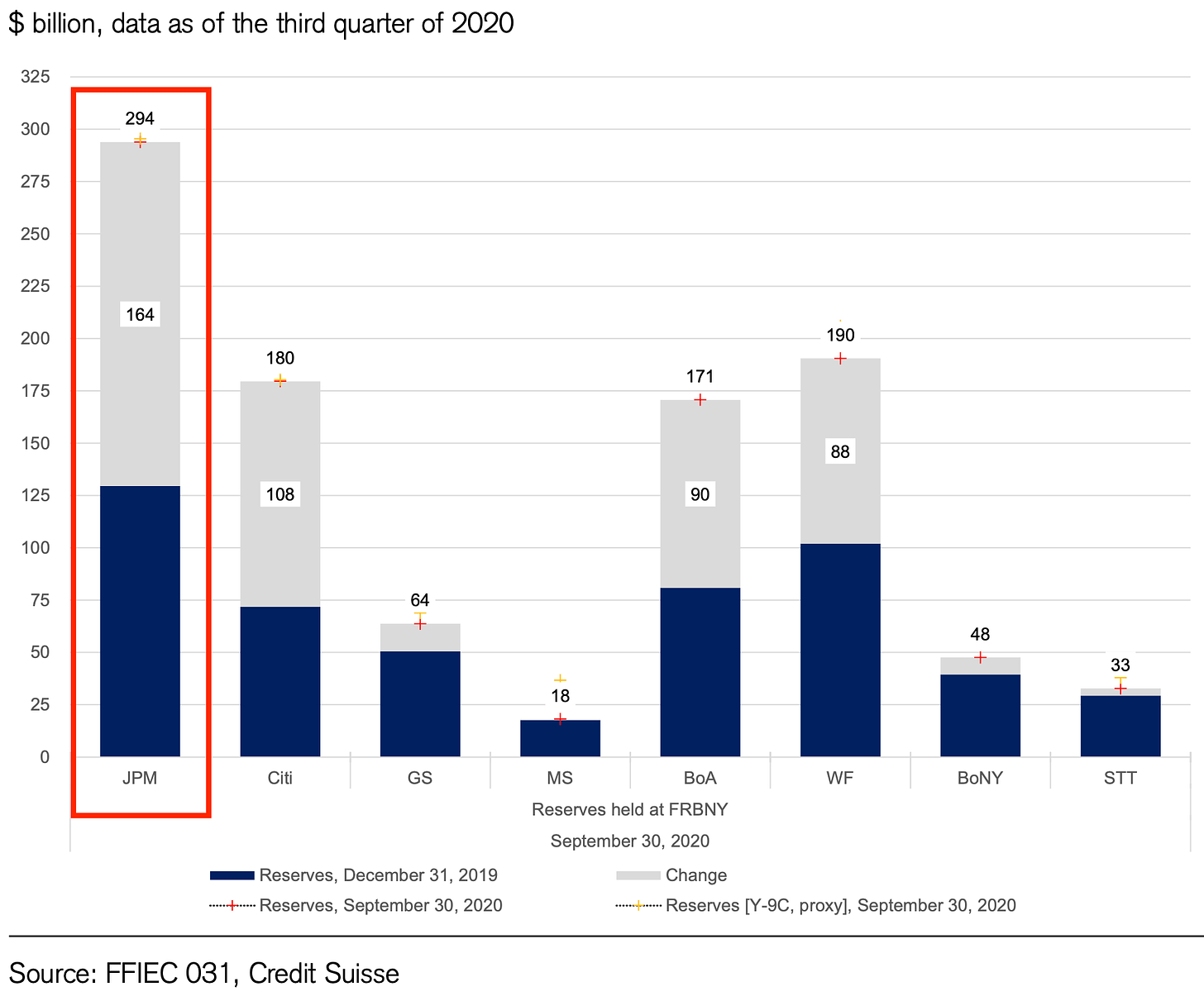

The boom in interbank lending, where big banks like JPMorgan borrowed Federal Funds (interbank reserves) overnight from smaller regional banks to cover funding shortfalls, was over. The Fed had injected trillions of reserves into the system (through QE asset swaps with primary dealers), but the Wall Street banks were the largest recipients. The most systemically important entities in global finance would never run into significant liquidity issues ever again. At least, that was the theory. In reality, the Fed had switched from one fairly unstable system to a fairly stable successor.

By drowning the system with reserves, the old “corridor” system of setting interest rates by adding and removing settlement balances had broken down. In its place, the Fed implemented a “floor” system, where officials would influence rates between a target range that they deemed appropriate. At the same time, monetary architects at the BIS (the self-described bank of central banks) had decided it was time to try to eradicate the concept of major banks collapsing, once and for all. Their solution? Turning reserves into the financial system’s primary safety mechanism.

By enacting what over many years of trial and error became the Basel Framework, the global regulatory establishment turned the biggest financial institutions, mostly money center banks, from cautious speculators into monetary fortresses. But they paid a price for security. The “alphabetti spaghetti” regulatory ratios — namely LCR, NSFR, and SLR — imposed on banks hampered their ability to engage in anything other than tedious financial activities. Not only were exotic financial trades off the table but even serving financial markets grew challenging.

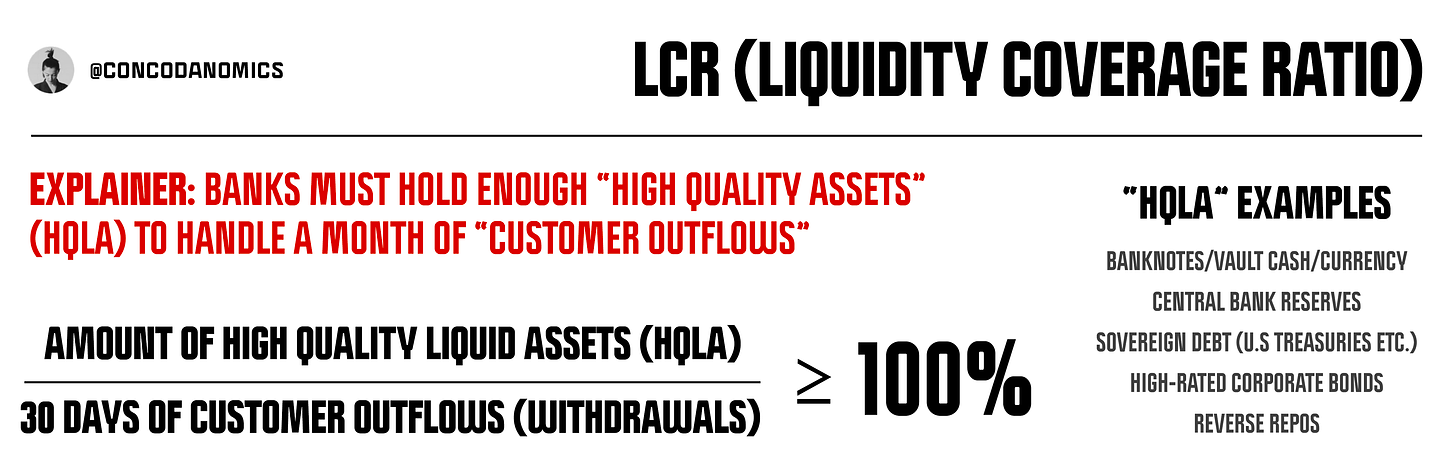

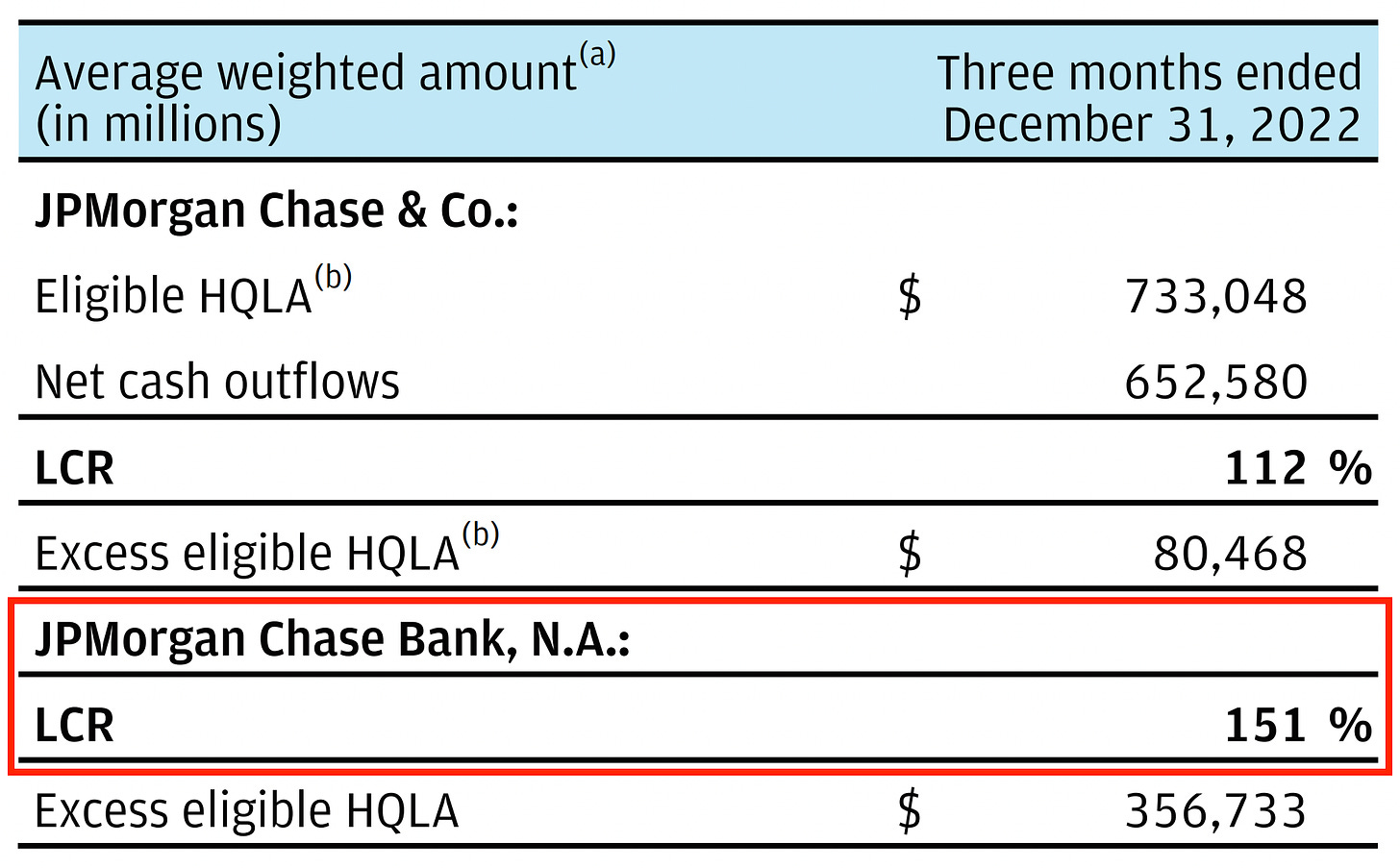

First came the Liquidity Coverage Ratio, known as LCR, devised in December 2010 and fully endorsed by regulators at the start of 2013. This ruling constrained a bank’s ability to increase the size of its balance sheet (hence leverage) by forcing it to raise a subsequent amount of equity (meaning retained earnings and common equity shares) to do so. But that wasn’t all. On top, banks had to maintain a sufficient portfolio of “HQLA”, high-quality assets comprising mostly of bank reserves and U.S. Treasuries, plus a lower percentage of other “safe assets”, at any one time. The complex calculation, which differs bank-to-bank, can be simplified to one, easy-to-understand fraction. Using a methodology provided by the Basel Committee, banks had to hold more high-quality assets (HQLA) than 30 days of customer outflows.

Regulators then took it one step further, encouraging banks to consider 100% as a limit and 125% as an adequate cushion to survive any systemic calamity. Most financial entities obeyed, with most banks increasing their LCRs to 125% and staying there, like JPMorgan.

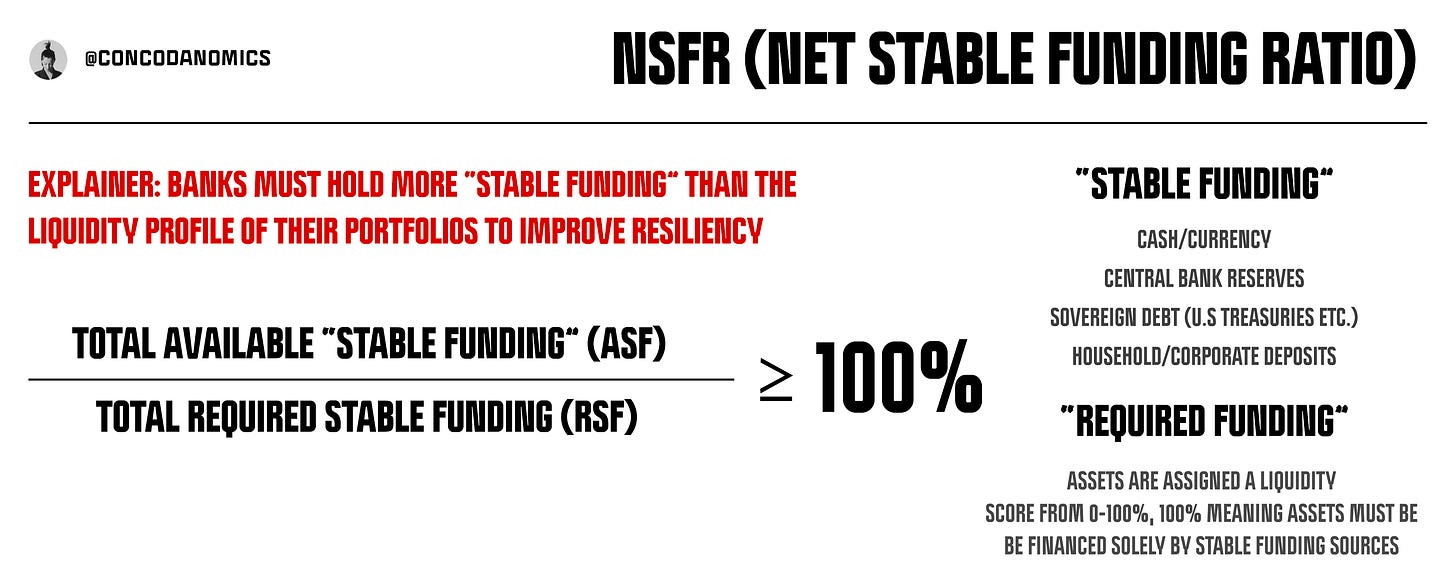

But central planners still weren’t satisfied. Alongside the LCR, the Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) began to impede banks’ risk-taking abilities further. After banks failed to sufficiently estimate, manage and control their liquidity risk in the build-up to the 2008 subprime collapse, the NSFR aimed to bolster a bank’s capacity to meet outflows over longer horizons. That meant holding even more stable funding against “stable assets”.

By assigning assets with certain haircuts and weights based on maturity and the likelihood of loss of funding during stress periods, monetary leaders hoped to boost banks’ liquidity, not just in the short term with the LCR, but over longer periods with the NSFR. Combined with other regulations, NSFR forced banks to reduce their liquidity risk, replacing “flightier” deposits (like those of institutional investors) with more retail deposits and longer-term debt, forms of funding that the NSFR’s architects deemed the most resilient to runs.

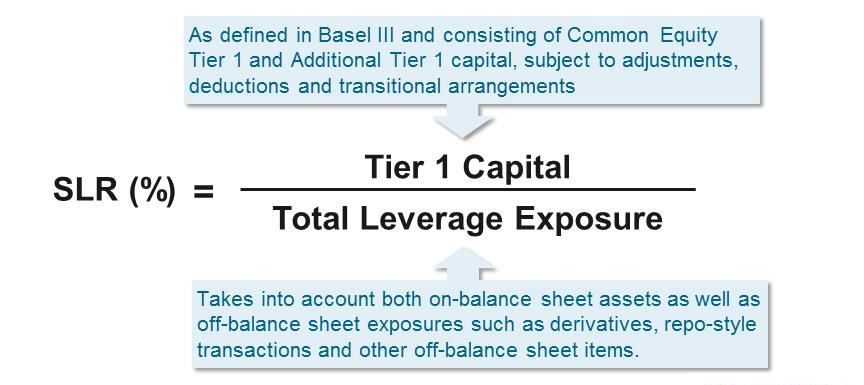

Even then, the regulatory apparatus believed that one more systemic weakness had to be eliminated. During the subprime boom, mortgage-backed securities (MBS) were deemed so safe that banks couldn’t imagine a scenario in which they became worthless. What’s more, banks believed they’d taken out “risk-free” credit default swaps (CDS) against their MBS holdings. Yet it turned out that both CDS and MBS were deemed worthless by the market.

To prevent a recurrence, regulators created the SLR (supplementary leverage ratio), the most restrictive regulatory ratio yet. The SLR considered all assets, even U.S. Treasuries and reserves (deemed the most liquid and safest assets on the planet) as potentially tainted, a belief that was eventually validated by the COVID-19 market meltdown. The more systemically important you had become, the larger amount of capital you already had to hold against your balance sheet’s leverage. But the SLR went a step further: Reserves and U.S Treasuries were deemed just as taxing as mortgage-backed securities and credit default swaps.

The regulatory endgame of Basel was a global financial system in which holding reserves became integral. The LCR/NSFR standard, paired with a Fed and other central banks injecting trillions of reserves into the system, had rendered the concept of “excess reserves” futile. “Big is necessary. It is the future,” one infamous rates strategist declared, “Get over it…”

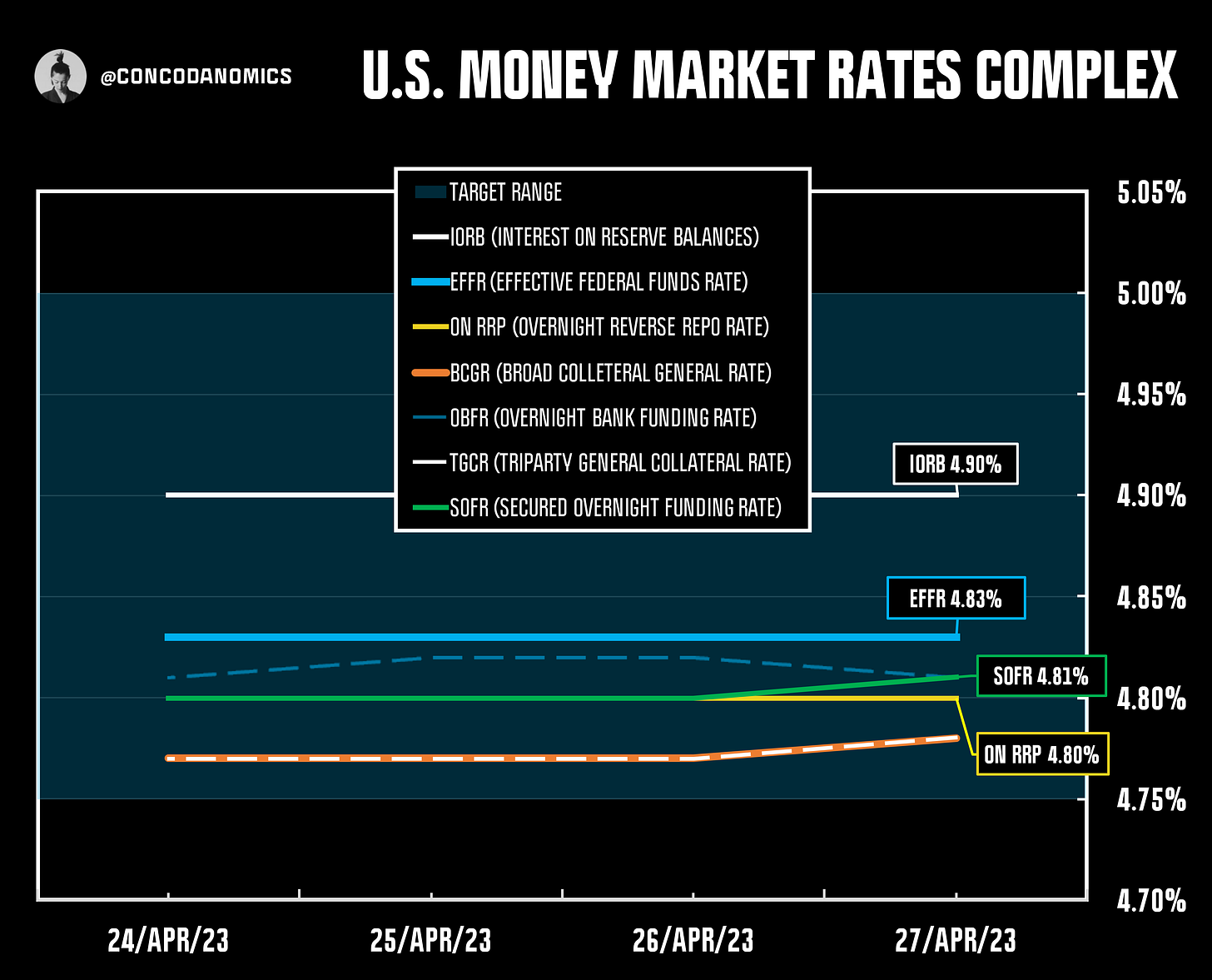

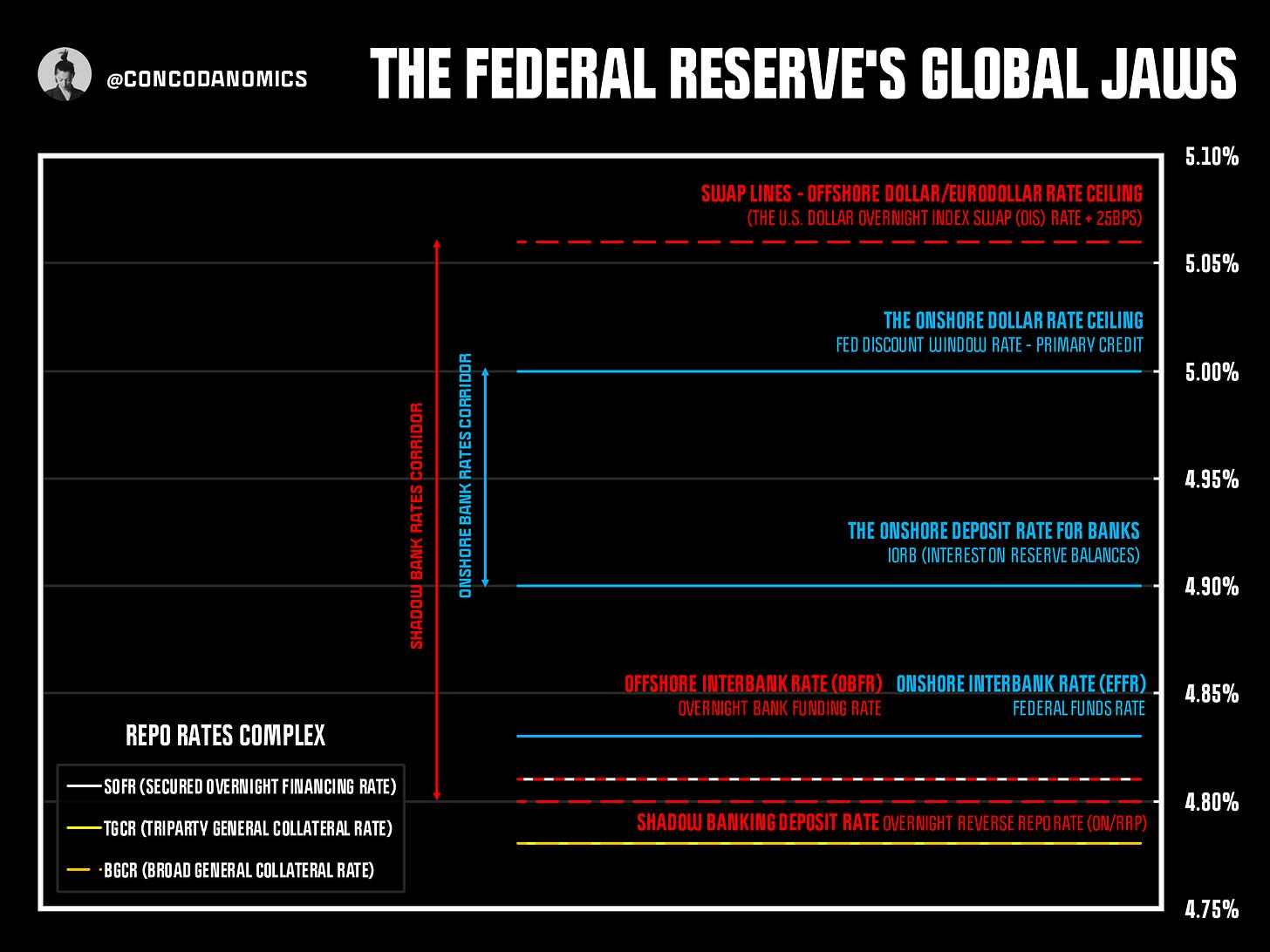

Over the last decade or so, the major global financial players have adapted to what the Federal Reserve dubbed an “ample reserves” regime. Since central bankers could no longer control interest rates by adding or subtracting a small number of reserves, they attempted a new technique. We witnessed the rise of what Conks calls the Jaws of the Fed™. The U.S. central bank, through various types of monetary alchemy, attempted to control numerous money market rates — including shadow rates like those of the repo market complex — within a self-determined range, all in order to accomplish its policy objectives.

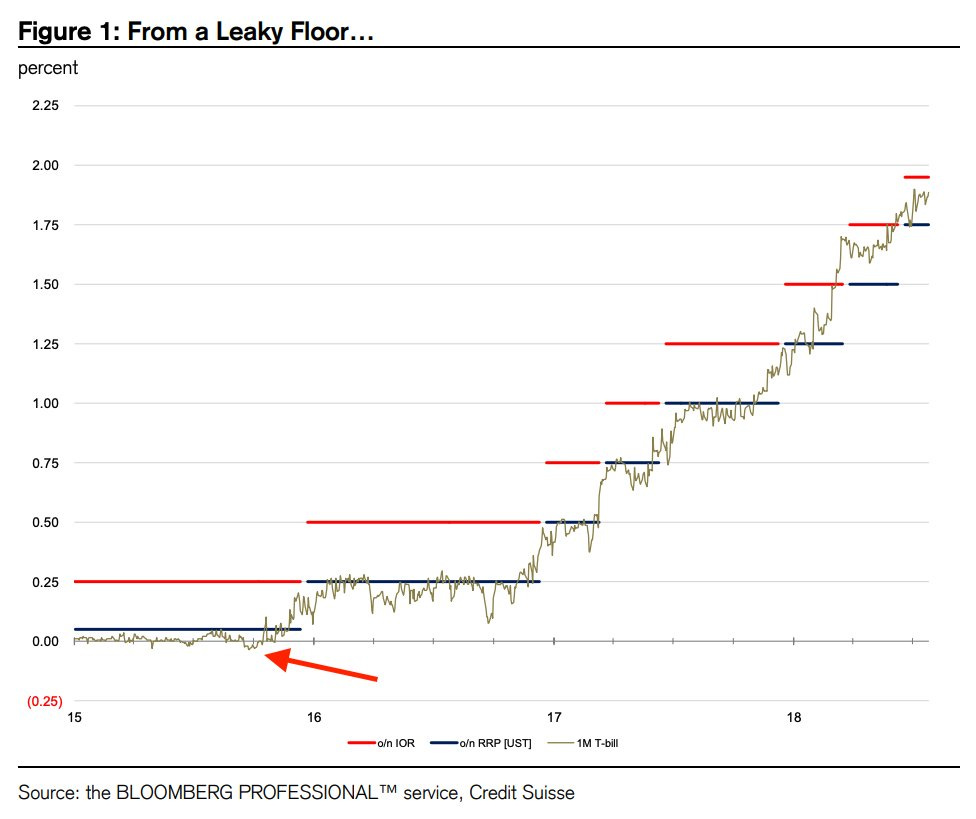

It quickly became clear that the Fed’s new system was flawed in many ways. Whenever the U.S. Treasury went on a “printing” binge, the rate on Treasury bills fell below the bottom of its target range. Fast forward to September 2019, both Fed Funds (the Fed’s benchmark rate) and rates in the repo market shot through its target range’s upper limit. The Fed was then relying on its main footsoldier JPMorgan to bring rates back into place. With the megabank possessing the most reserves after endless QE injections, it should have stepped in as the Fed’s last line of defense.

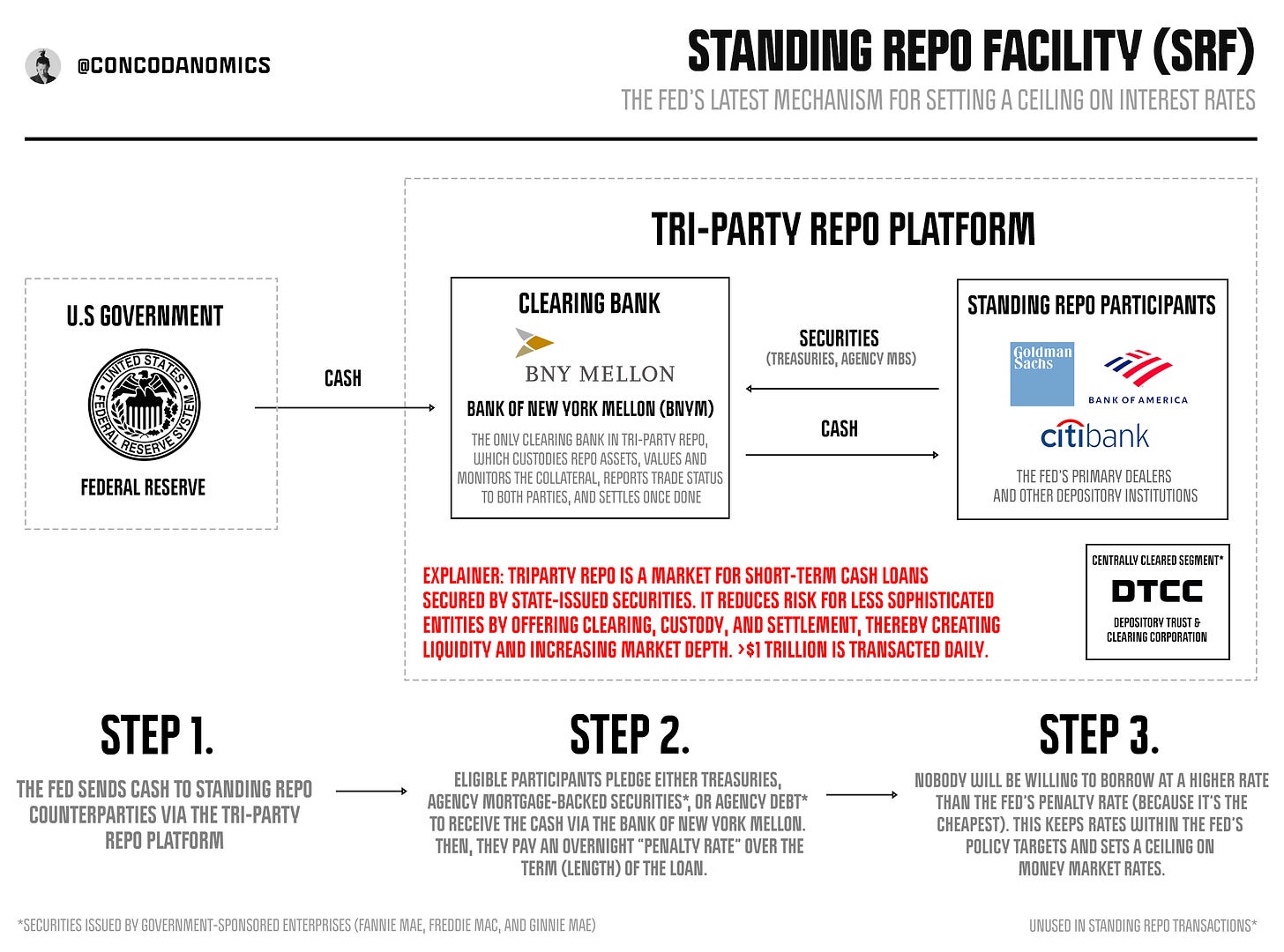

But the Wall Street behemoth never obliged. The Fed’s “next-to-last lender of last resort” failed to intervene, leading monetary officials to offer emergency cash via (yet another) one of the Fed’s creations: the Standing Repo Facility, or (SRF). As nobody would borrow at a rate higher than the Fed, this set a hard upper “jaw” on borrowing costs for all market players.

Finally, after multiple interventions and monetary alchemy, the Fed had enforced a hard upper limit on its local rates complex. The Fed’s Discount Window and the SRF stood guard against any disorder, offering unlimited U.S. dollars — though at a premium. But the U.S. central bank’s job was far from over. In the American-led order, the Fed’s jaws were never truly local but global.

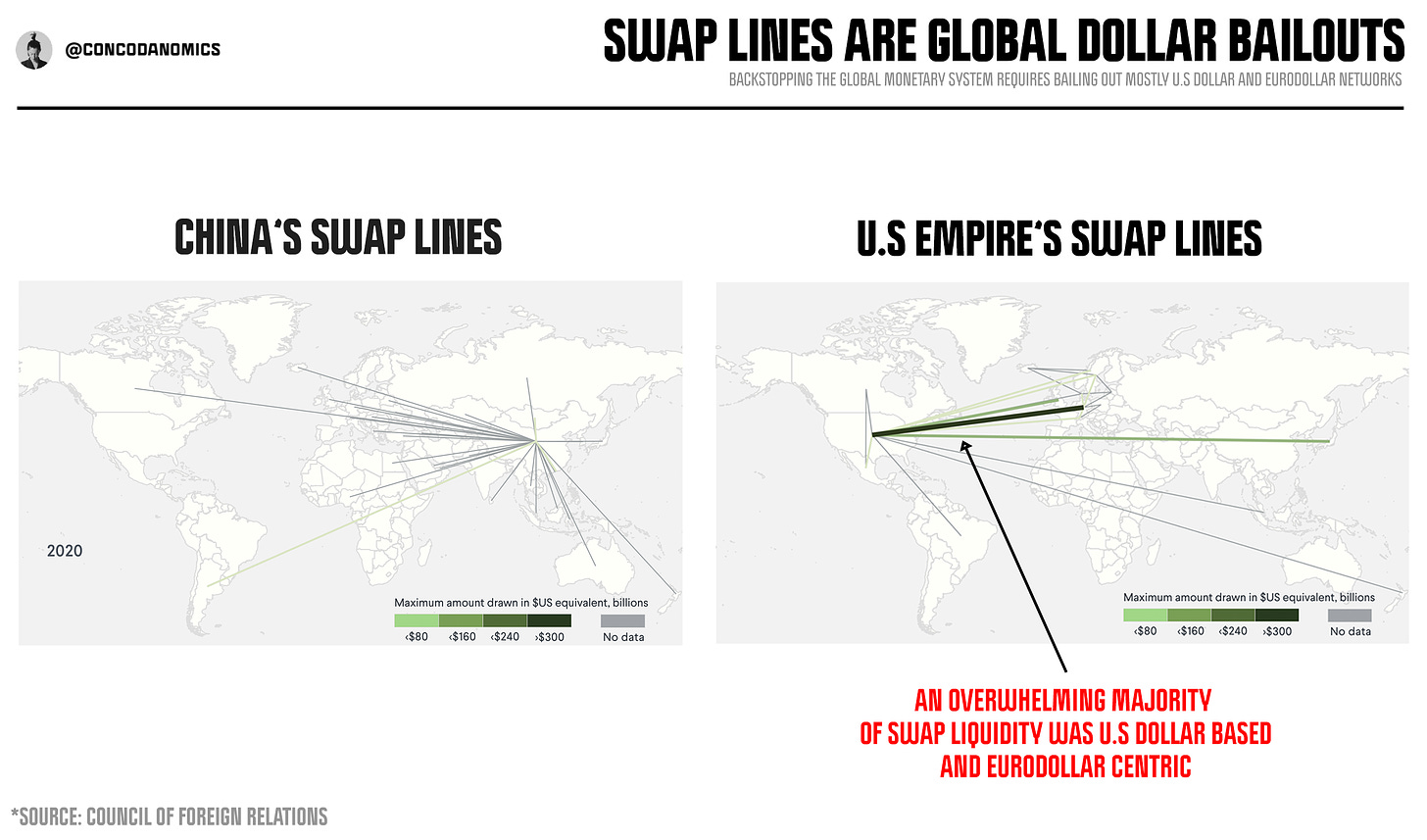

The real upper jaws were the swap lines that the Fed initiated to supply the world with an unlimited pool of emergency dollars. Until last month’s mini-banking panic, the world had forgotten that in both 2008 and 2020, the Fed had fired up its dollar swap lines to bail out almost every dollar funding paradigm, primarily the Eurodollar system.

Early this March, the Fed’s upper global jaw sprung into action once again, stemming any global contagion and preserving the U.S. dollar status quo. The world was reminded of the Fed’s global presence.

Still, this credit crunch should have sparked chatter over the U.S. central bank’s remaining dilemma. The Fed’s upper jaws remain solid and reliable but the Fed’s lower jaws possess a death-star-like vulnerability, one that will need to be patched eventually. The global rates corridor the Fed has set up remains “leaky”.

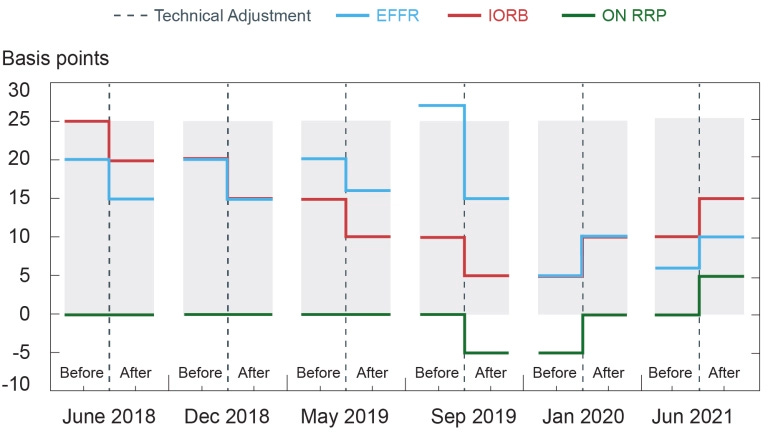

In most scenarios, the Fed has adequate tools to deal with a leaky lower jaw and can push rates back into its target range. It does this by either issuing a huge amount of Treasuries, making “technical adjustments”, or altering limits and access to some of its facilities.

The problem, however, is this only works on a domestic level. Its lower jaw remains vulnerable on a global scale. The Fed has a global fault where not all dollar users have access to its facilities, thus no global version of a dollar rates floor exists. That’s about to change.

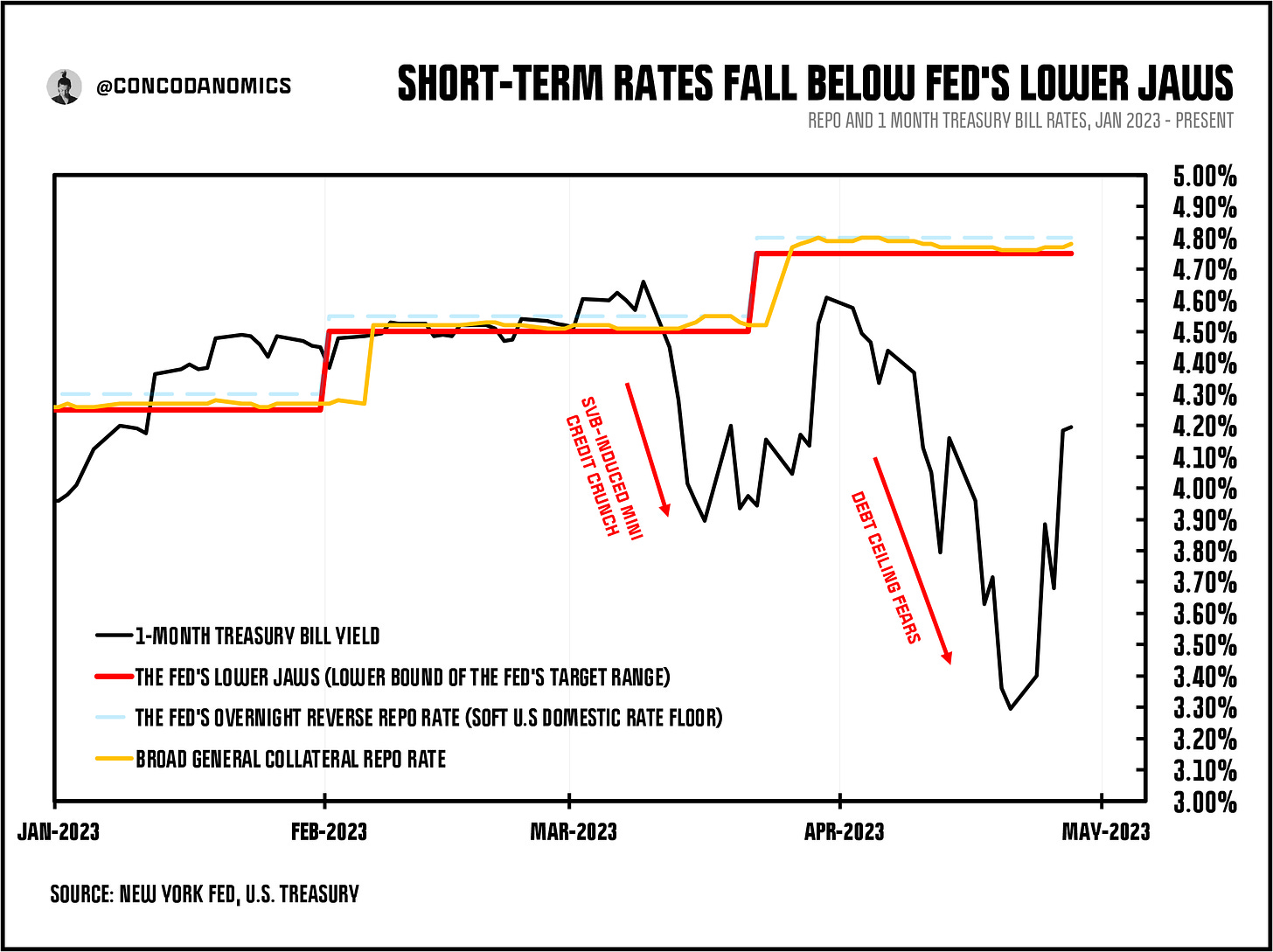

The recent plunge in short-term Treasury yields has sparked rumors of a “collateral shortage”, with various money market rates falling below the Fed’s RRP (reverse repo rate), and even some tumbling toward the Fed’s lower jaw .i.e the lower bound of the Fed’s target range.

Even so, this is not the catalyst that will prompt the Fed to fix its lower bound. Every time a “pre-debt ceiling doomsday” arises, a breach of the Fed’s target range tends to ensue, with monetary leaders expecting it. Instead, another trigger will likely spur them into action. The event that will force the U.S. central bank to install a solid global dollar rates floor, however, remains unclear. But since every other defect in the Fed’s jaws has been pushed to the point where officials had to intervene, a global “hard lower jaw” seems inevitable.

At some stage, most likely when the Fed’s tightening prompts a more significant credit crunch, monetary leaders will choose to patch the hole in its global jaws, once and for all. The Fed will open up access and offer liquidity to anyone, especially those posing risks to the status quo. Foreign entities will gain entry to the facilities that offer dollars within Fed-approved rates, and only then will the Fed’s jaws be complete. What provokes the U.S. central bank to make such a move, is now the more pertinent question.

If you liked this, feel free to hit the ♡ button to let us know and share a link via social media to help us grow. Comments are also encouraged. Thanks for supporting macro journalism!

EFFR, OBFR, SOFR, TGCR, and BGCR are subject to the Terms of Use posted at newyorkfed.org. The New York Fed is not responsible for publication of tri-party data from the Bank of New York Mellon (BNYM) or GCF Repo/Delivery-versus-Payment (DVP) repo data via DTCC Solutions LLC (“Solutions”), an affiliate of The Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation, & OFR, does not sanction or endorse any particular republication, and has no liability for your use.

I’m curious why you describe the unsecured/fed funds system as unstable. Seems like the secured system is less so, especially since the 2008 crisis was a function of declining collateral values. The Fed described the floor system as easy to manage but it has proven rickety. Sep ‘19, Mar ‘20 point to a fragile system requiring constant, dramatic intervention to maintain. By contrast, the unsecured federal funds system maintained by a corridor worked pretty well. See Bill Nelson’s “I don’t know why she swallowed the fly”

It seems like whatever the banking system turns to as a “safe” bet inherently becomes unsafe because anything that a failing system uses will eventually weaken as a result of the failing system itself

Hope that makes sense