An unreported battle has been brewing deep in the most critical market globally, a struggle for power within America’s sovereign debt market. Now, after recent events, this battle is approaching its most crucial moment.

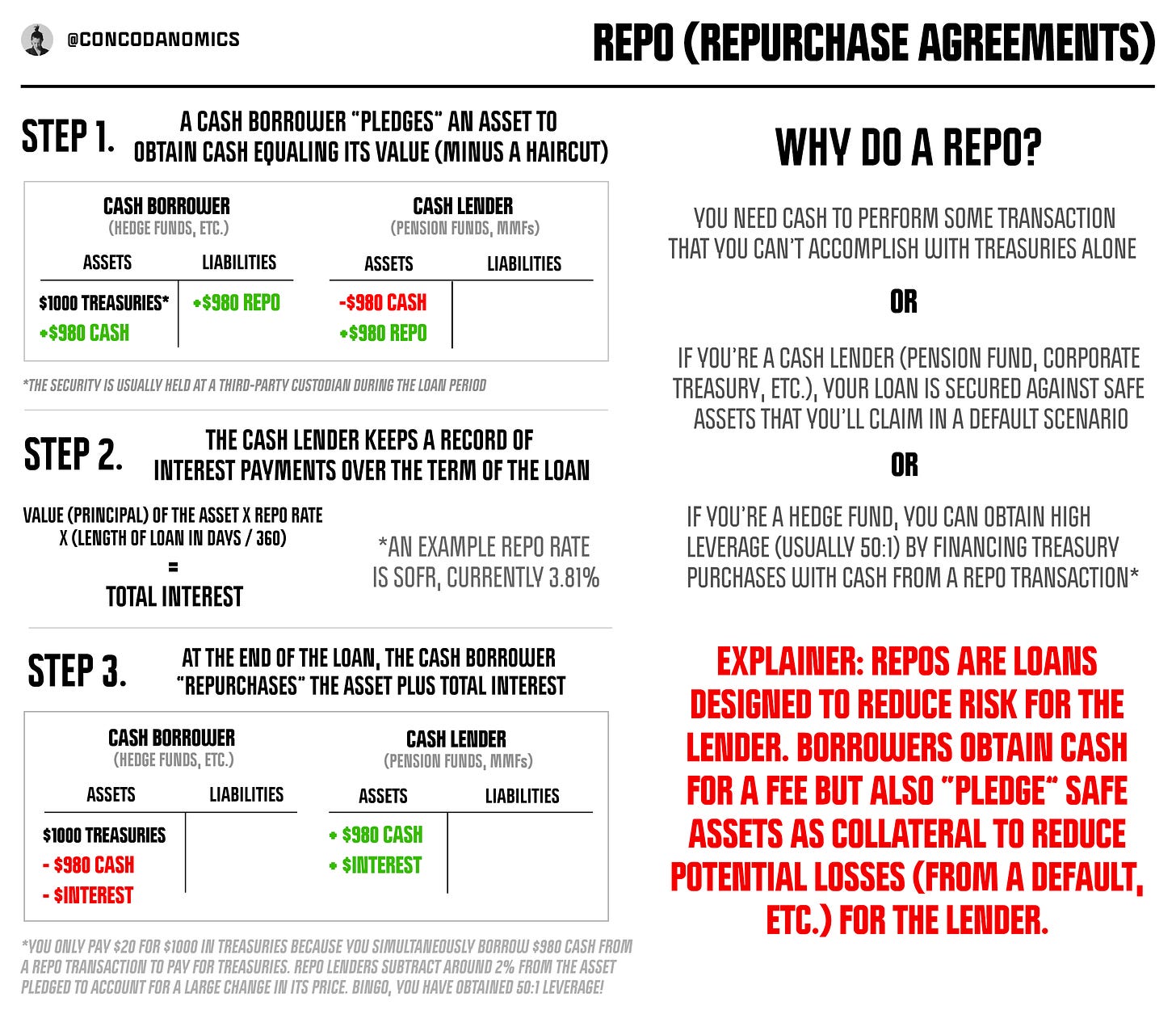

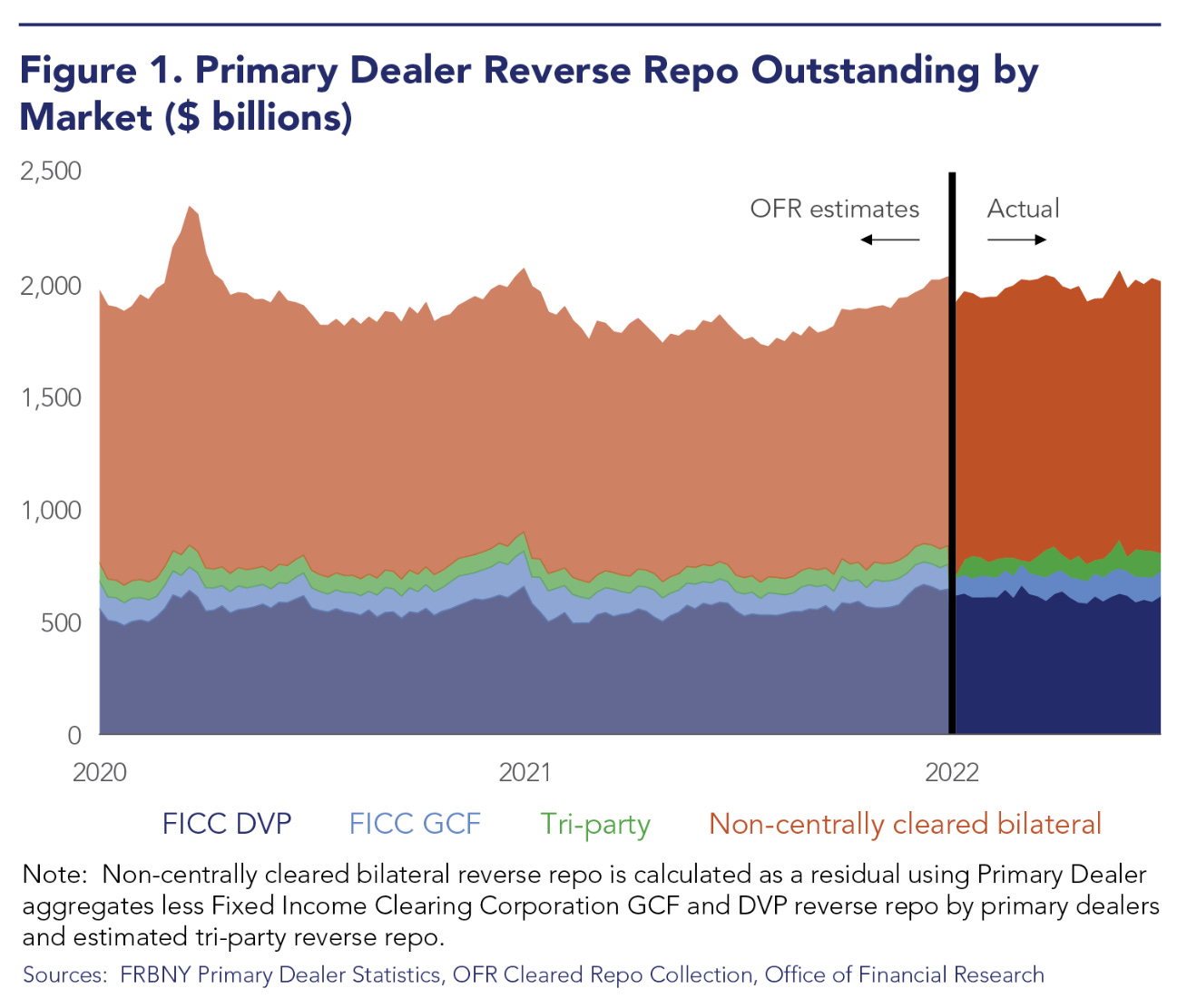

In December last year, Conks reported on the rising hazards in the largest, yet most obscure, market for money. An estimated $2 trillion or more in dollar loans had built up in the shadows, growing to become the most significant part of the repo market, where participants borrow cash overnight (or over another short period) by pledging collateral, usually Treasuries or state-issued mortgage-backed securities.

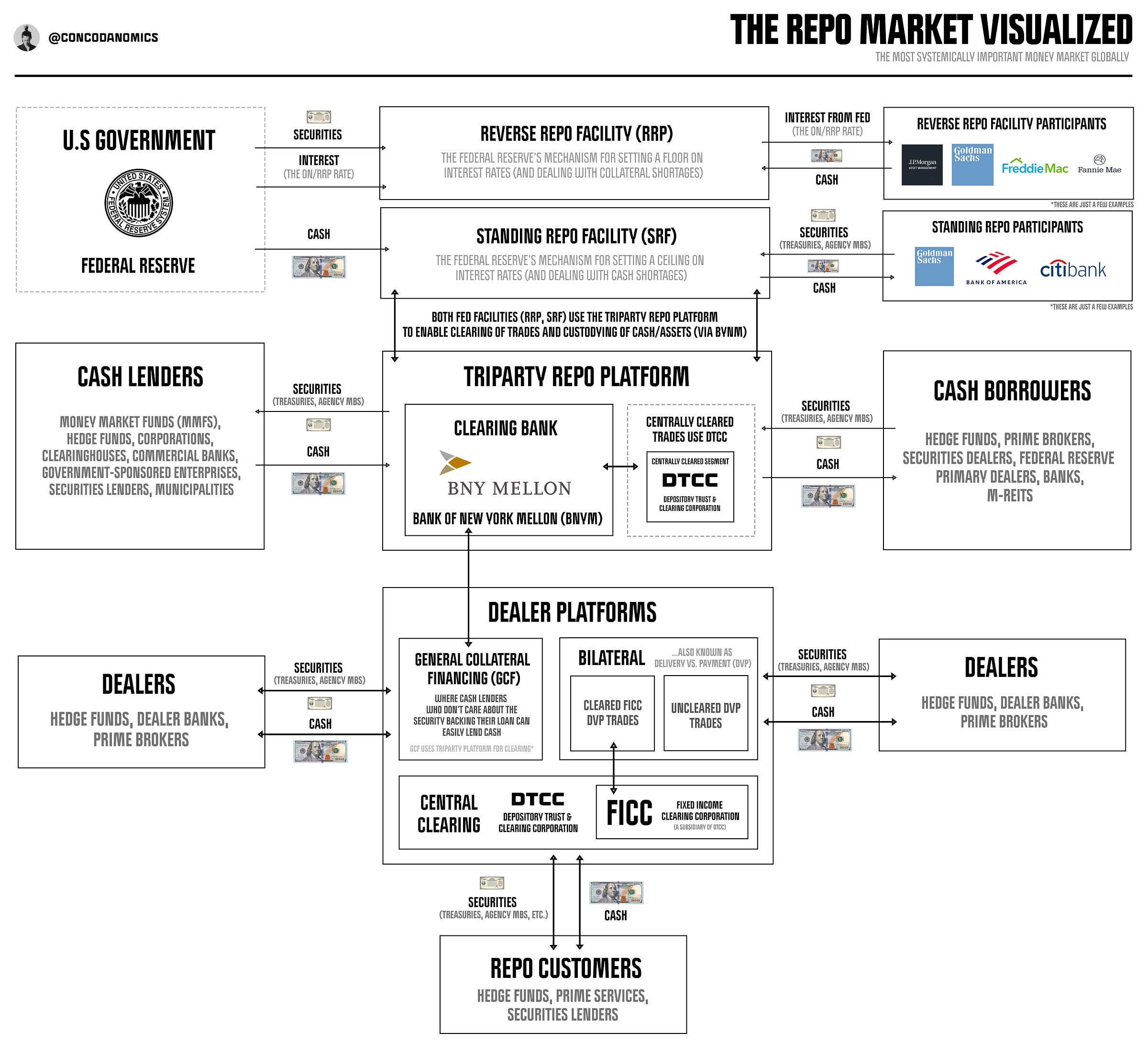

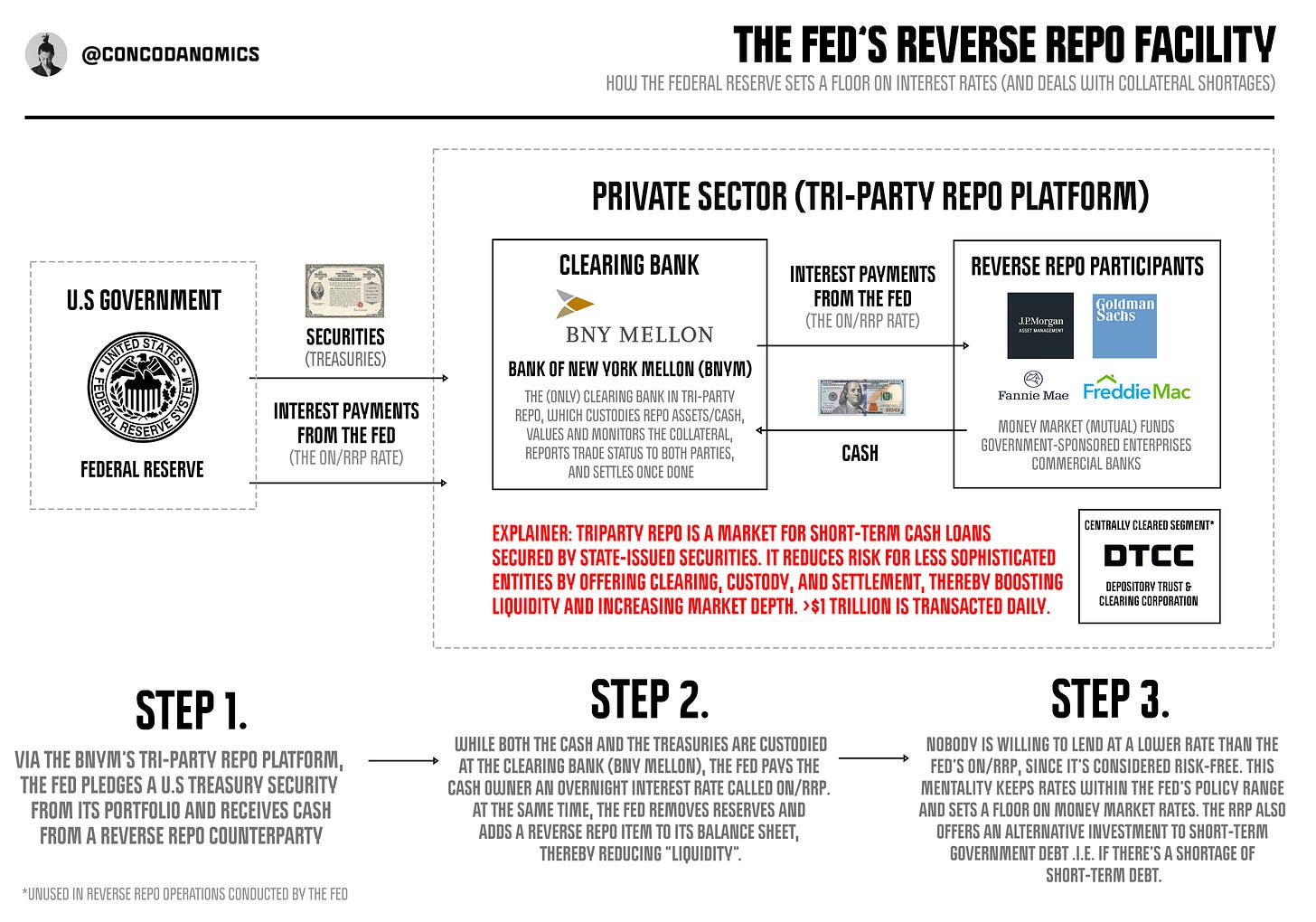

The repo market consists of four parts: the cleared and uncleared segments of the “triparty” platform, which connects cash investors with cash borrowers including the Federal Reserve, plus two dealer segments: general collateral financing (GCF) and bilateral (i.e. only two parties involved the trade).

Triparty repo gets its name from the three parties involved in a transaction. Cash lenders, from corporations to money market funds, lend to cash borrowers (mostly hedge funds) via the Bank of New York Mellon (BNYM). The Fed also uses BNYM’s platform to conduct its monetary policy operations.

Over the last decade, the financial world has pivoted to using “market–based” funding, mostly from repos. The so-called shadow banking sector, which includes money market funds (MMFs), the repo market, and the Eurodollar system, now facilitates more than twice the funding activity of Wall Street.

Banks, minus a few hiccups and panics, now serve as boring utilities. Since the global financial crisis (GFC), leaders chose a world in which Wall Street’s survival was paramount to creating “stability”. They deemed the failure of JPMorgan and other G-SIBs (global systemically important banks) as an extinction-level systemic event.

Banks were thus forced to hold and raise much more capital than before the GFC, prompting several shifts in how global finance operated. The major banks, for example, issued a mammoth amount of bonds to make up for a poor amount of lending.

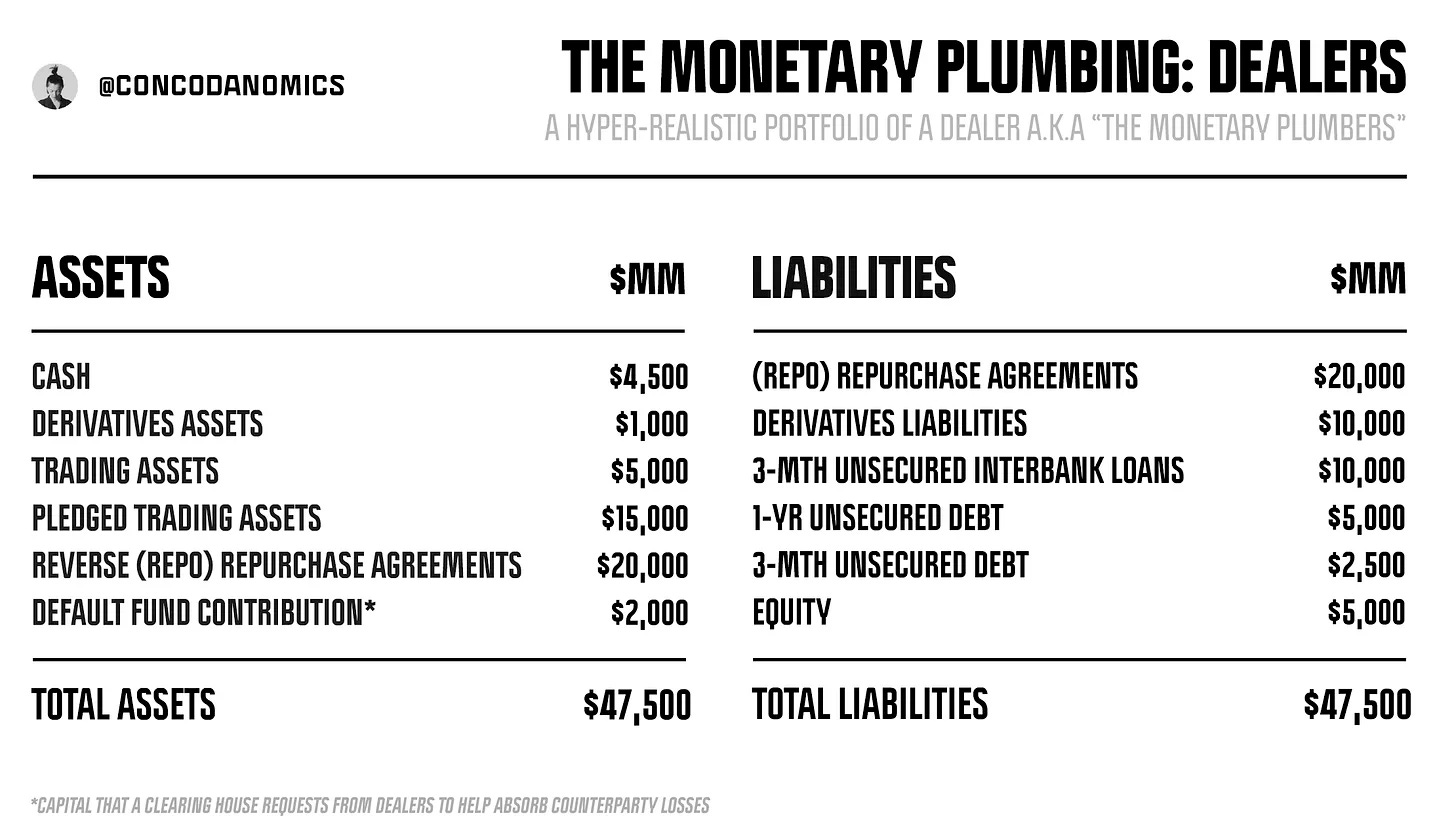

Because of an ocean of regulatory frameworks and rules enforced post-GFC, systemic risk shifted from the banks to shadow entities, like MMFs and securities dealers. Subsequently, the shadow entities started to absorb most of the systemic risk and moral hazard. Monetary authorities hoped these entities using Treasuries and MBS to fund their operations was a long-term durable fix.

In the regulator’s eyes, they deemed the decline in liquidity caused by big banks retreating from risk as ideal, not an “unintended consequence”. Offloading the consequences of crises onto non-systemically important entities was done to protect the systemic ones from harm. This then allowed the repo market to become the most common way to borrow cash and obtain dollar funding.

Despite the repo market’s perceived safety, however, it’s far from foolproof. With the 2014 Treasury “flash crash”, the 2019 repo crisis, and the near failure of the Treasury market during COVID-19, another monetary mishap will surface regardless. The clock has been ticking to shed light on the most ominous hazard: uncleared bilateral repo (UBR), one of the most elusive (and exotic) funding markets. Unlike other parts of repo, UBR trades have remained anonymous, skipping central counterparties and custodians.

Only a few weeks ago, the U.S. authorities confirmed that trillions of dollars in outstanding transactions had been executed in the shadows. The Treasury’s Office of Financial Research revealed its long-awaited data pilot on this multi-trillion dollar market.

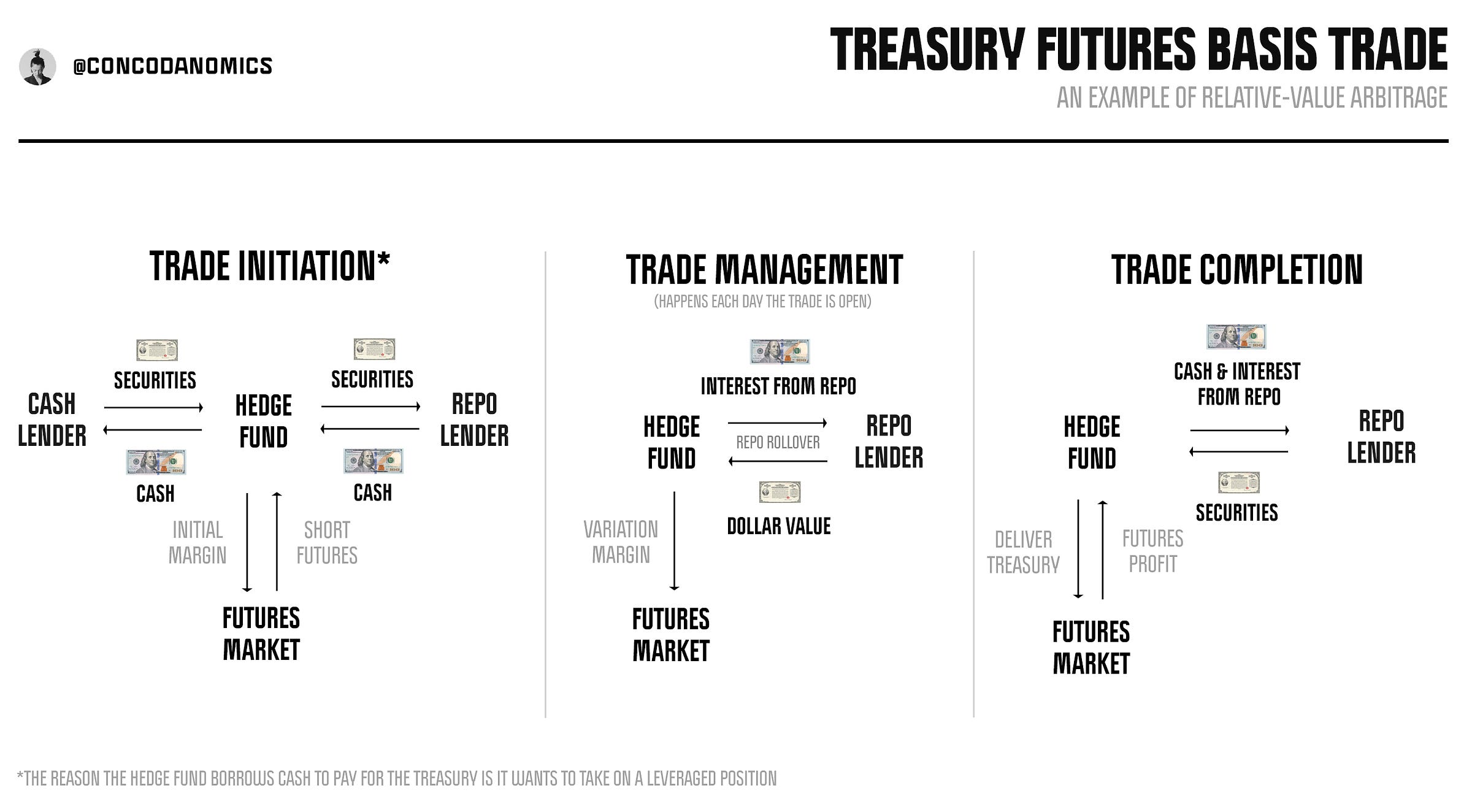

Regulators have become particularly concerned about letting what’s known as the '“leveraged community” operate in secrecy. These parties are mostly hedge funds, which use the UBR repo market to obtain large amounts of leverage (around 50:1 or higher) to place elaborate trades. These include relative value arbitrage, like capturing the spread between newly issued Treasuries and older issuances, plus the Treasury “futures basis” trade, which employs repo to exploit dislocations between Treasury securities and associated future contracts.

Some officials in the regulatory establishment are not just aware of how these trades blew up during COVID-19, which exacerbated the Treasury market turmoil. They have cited another infamous blowup: the failure of Long Term Capital Management, or LTCM. In 1998, LTCM built up large counterparty exposures in the “uncleared bilateral segment” of the repo market, executing transactions with roughly 75 different counterparties. Meanwhile, these parties had no knowledge of the risks LTCM was taking.

Like how the reckless management of Silicon Valley Bank led to a run on regionals, LTCM’s enormous exposures in repo led to a bailout that stopped contagion from spreading. Had the authorities failed to intervene, liquidations could have resulted in a systemwide meltdown.

As with every other financial “episode” we’ve witnessed so far, the Fed, U.S Treasury, and other agencies not only intervene but increase their authority and oversight. Recently, finding points of failure and subduing systemic risk are becoming a top priority. Leaders have (slowly) proposed a multitude of actions to increase transparency in the dark areas of markets, including collecting adequate data on hedge funds and private equity, increasing the quality and frequency of market data, and even identifying participants’ actions.

But this coming era of transparency in money markets likely won’t start with repo, the most intricate market out there. Instead, it will start with the Treasuries, the most systemically important market globally. Changes made there will more likely propagate to other areas.

Over the years, it’s become clear that monetary leaders plan to achieve their aims via implementing “all-to-all trading” in the Treasury market. This enables any party to transact with any other, a format that many stock and derivatives exchanges already use today.

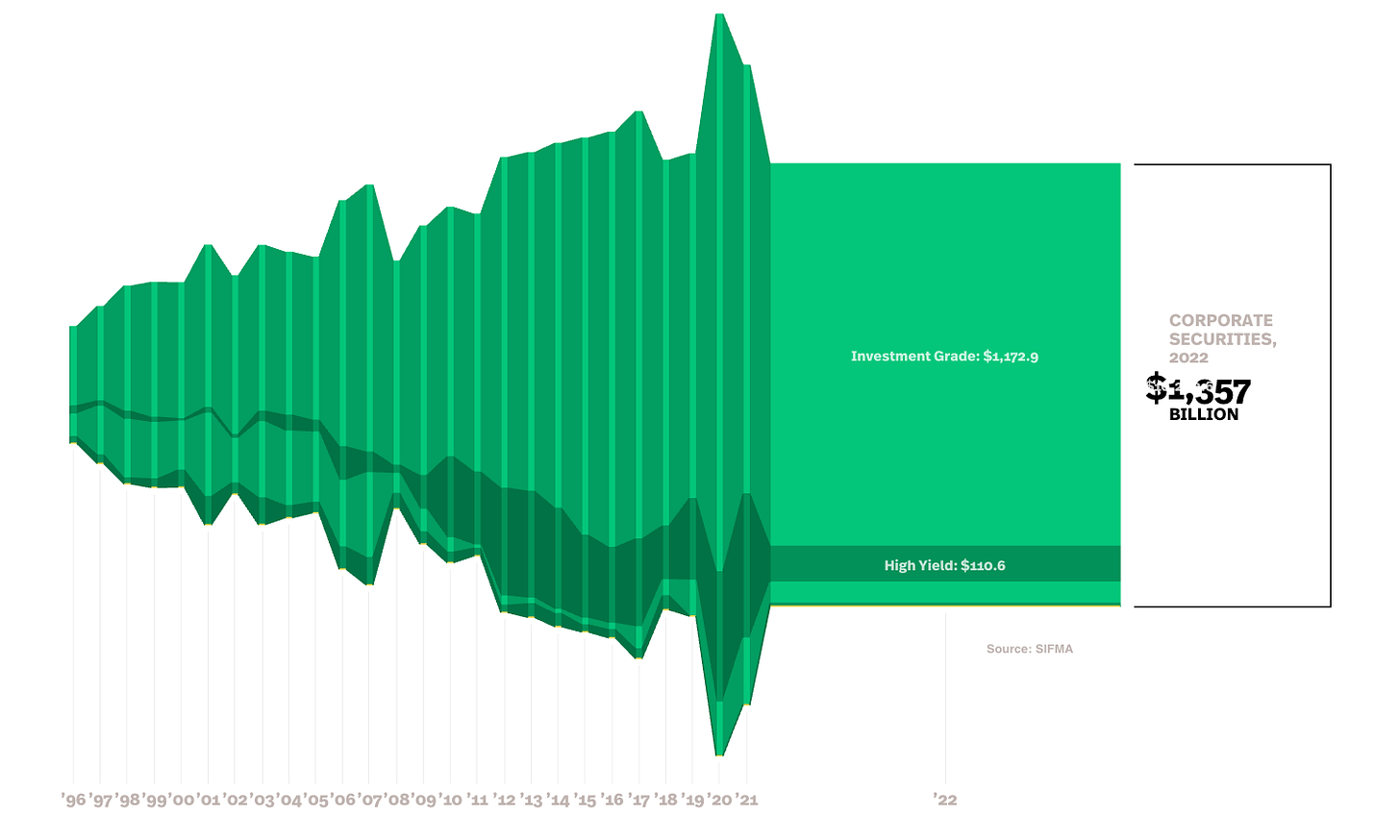

In a pure all-to-all trading setup, the barriers to entry would fall to extremely low levels, allowing nearly any investor type to participate in the secondary market for Treasury securities. Eventually, that could even include easy access for everyday citizens. Implementing all-to-all trading in the Treasury market would be one of the first steps to democratizing today’s complex markets, increasing the number and variety of participants and reshaping the competition among them. Market liquidity would flourish. Researchers recently discovered that even a tiny amount of all-to-all trading in the corporate bond market created not only a more competitive environment but also enhanced liquidity and lowered the cost of trading.

Conceptually, all-to-all trading also creates the prospect of widening the field of liquidity providers that participants can access. This would ultimately boost market depth, making the Treasury market more resilient to stress.

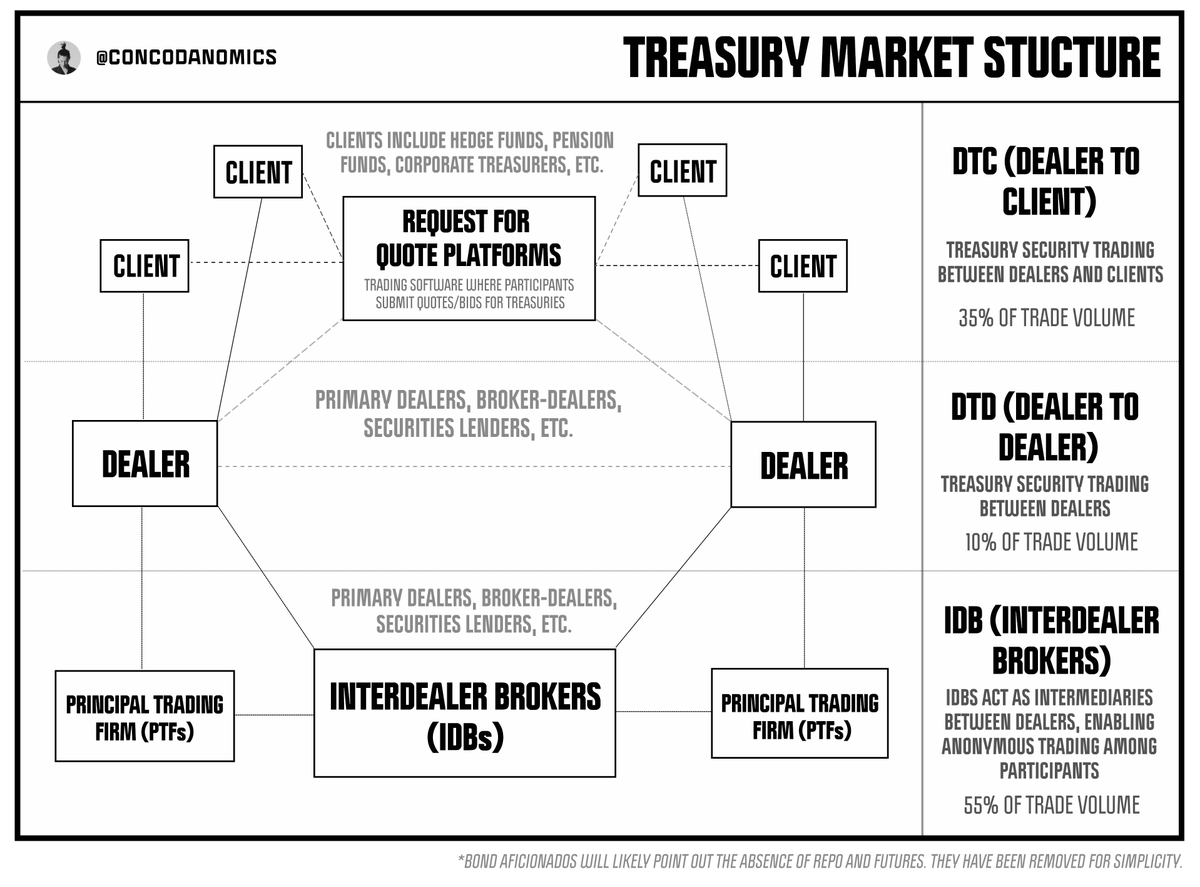

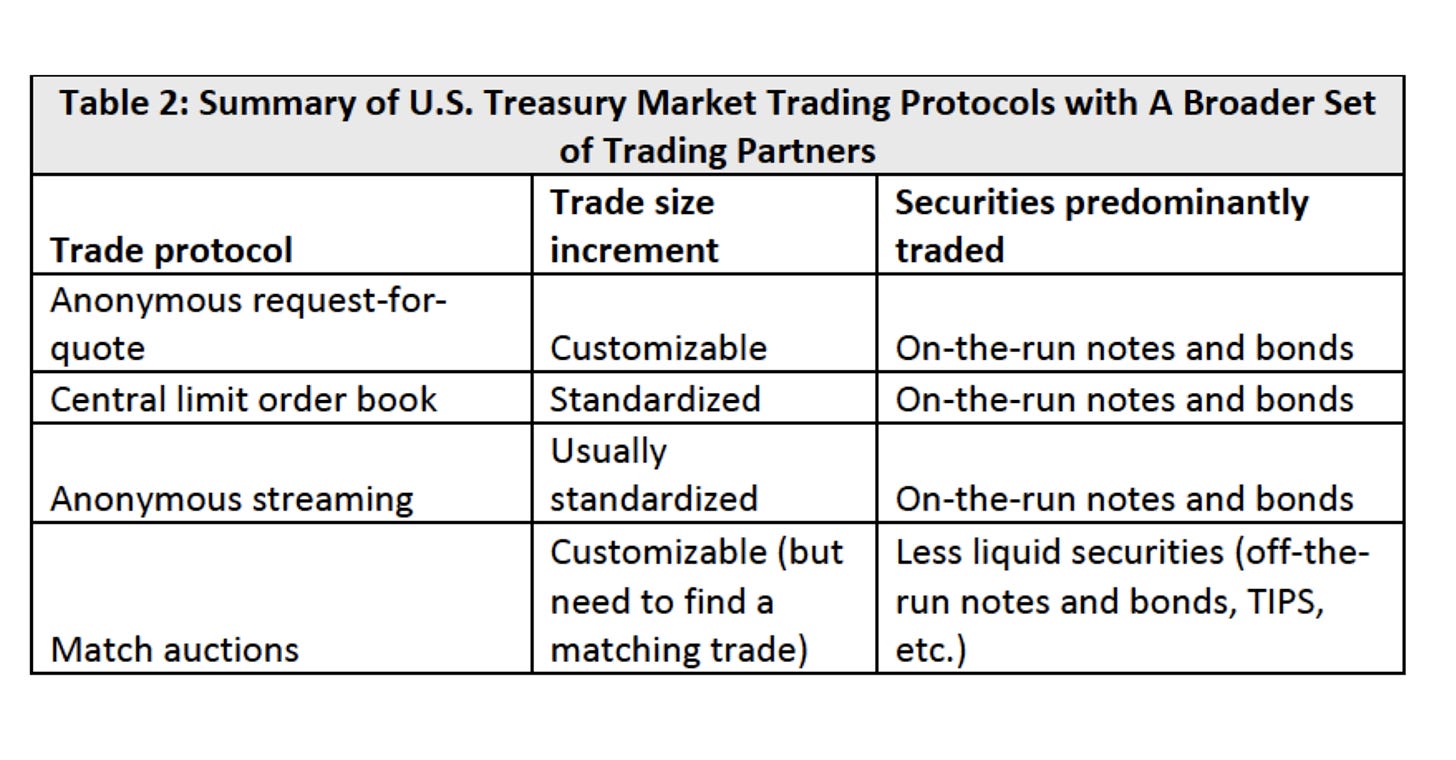

But it’s not that easy to implement. Even though it’s clear that all-to-all trading could expand the number of trading counterparties and improve efficiency, all while subduing market instability, a number of key challenges remain to achieve broader adoption. With the market for Treasuries being more elaborate than most, it’s a tough task to liberate it. For any participant to be able to trade directly with any other, the market’s current architects would not only have to modify but combine multiple complex protocols. Similar to that of the repo market, the Treasury market's structure is separated into “interdealer” and “dealer-to-client” segments. Merging these two elements would be the first (tricky) step to allow any party to trade Treasury securities with one another.

Then you’d have to merge the four types of trading protocols that exist within these two segments: “Request for quote” (RFQ), “central limit order books” (CLOBs), “anonymous streaming”, and “match auctions”. Each one serves a particular kind of function and market participant.

What’s more, the machines have taken over. Principal trading firms, known as PTFs, started to introduce automated trading strategies in the mid-2000s. And only a decade later, they have grown to become the major wheel-greaser of the Treasury markets. The former dominant players were traditional intermediaries, but after being able to operate with less capital than typical broker-dealers, PTFs took over. They operated using limited net exposure and have not been subjected to the same restrictions.

Extensive regulations introduced after the GFC changed dealers’ perceptions of risk, influencing their willingness and capacity to intermediate markets. Since the new rules stated Treasuries were now just as risky as any other asset, they had no chance of beating the PTFs.

Today, that battle is won and over. The war that Conks mentioned earlier is not a struggle for supremacy between dealers and PTFs. Instead, it’s between monetary authorities and major market players, a tiny number of principal trading firms that dominate trading volumes. The recent opacity of Treasury markets has caused decreased competition and increased inequality, allowing a few large PTFs to dominate smaller counterparts. But now, as authorities turn to fulfill their aims of transparency, the power balance is about to shift once again.

Since Treasuries will remain the benchmark for pricing trillions in securities and hedging positions in most U.S. dollar fixed-income markets, monetary leaders will favor transparency over monopoly, which a select number of players have assembled. Authorities won’t fully level the playing field or bring down power structures completely. Like with the stock market, a subset of participants typically act as liquidity giants and take the other side of most trades made by remaining participants. But they will have some impact. The major players will gradually see their power fade. Regulators will start to chip away at the dominance of a small number of PTFs, who’ve played a dominant role in price discovery and liquidity since this century began. The era of transparency will take precedence.

Some liquidity goliaths may withdraw as all-to-all trading creates larger capital and balance sheet costs, reducing overall liquidity. Yet monetary leaders are gambling on a sea of new participants, enabled by all-to-all trading platforms, to cancel out any shortfall. Since enhancing the resilience of the Treasury market has become a top priority, monetary leaders’ goals of reducing risk and opaqueness will likely prevail. Moreover, recent events will only urge the regulatory establishment to speed up their efforts. Their growing need to prevent calamity in multiple markets means an expansion of their power and influence is not just on the table. It’s about to advance at a pace we’ve never seen before.

Next on the agenda? America’s sovereign debt market.

If you enjoyed this, feel free to smash that like button and share a link via social media. Thanks for supporting macro journalism!

One way to do All to All is to create separate mechanism and begin to move treasury activity into that program.

Is there short-term data on Repo? I have no specific knowledge, yet I can only assume that the extreme levels of volatility in Treasuries - especially short-term, most especially intraday vol in 4/8-week bills since the SVB-debacle - does tremendous damage to repo-chains, as the increased vol needs to be mechanically countered by stronger haircuts, leading to degradation of funding.