Ever since World War II concluded, a one-of-a-kind monetary paradigm has been expanding and strengthening deep in the shadows of global finance: the Eurodollar system. Decades after its inception, it’s still difficult to envision how this eccentric yet enormous market operates. That is, however, until today. In this subscriber explainer, we’ll provide a definitive overview of the Eurodollar system and its mechanics, while answering the much-pondered question: “What are Eurodollars, really?”.

The most common origin story of the Eurodollar is that, in the early post-war era, America’s adversaries needed a place to store dollars outside the U.S. banking system to avoid unexpected seizures. Another version is that around the same period, global financiers discovered a way to profit from regulatory arbitrage by lending U.S. dollars overseas. Both accounts are accurate, yet the Eurodollar could only emerge out of what Conks calls America’s post-WWII “global security pact”.

Following World War II, the U.S. by default became the dominant global superpower. But rather than choosing to conquer the world, the Americans instead convinced almost every major power to partake in a global “de-arming”: unobstructed trade on an international scale, with the U.S. providing the armed personnel to subdue (almost all) major conflict. This not only facilitated the most prosperous period in human history but the rise of the first truly global geopolitical currency.

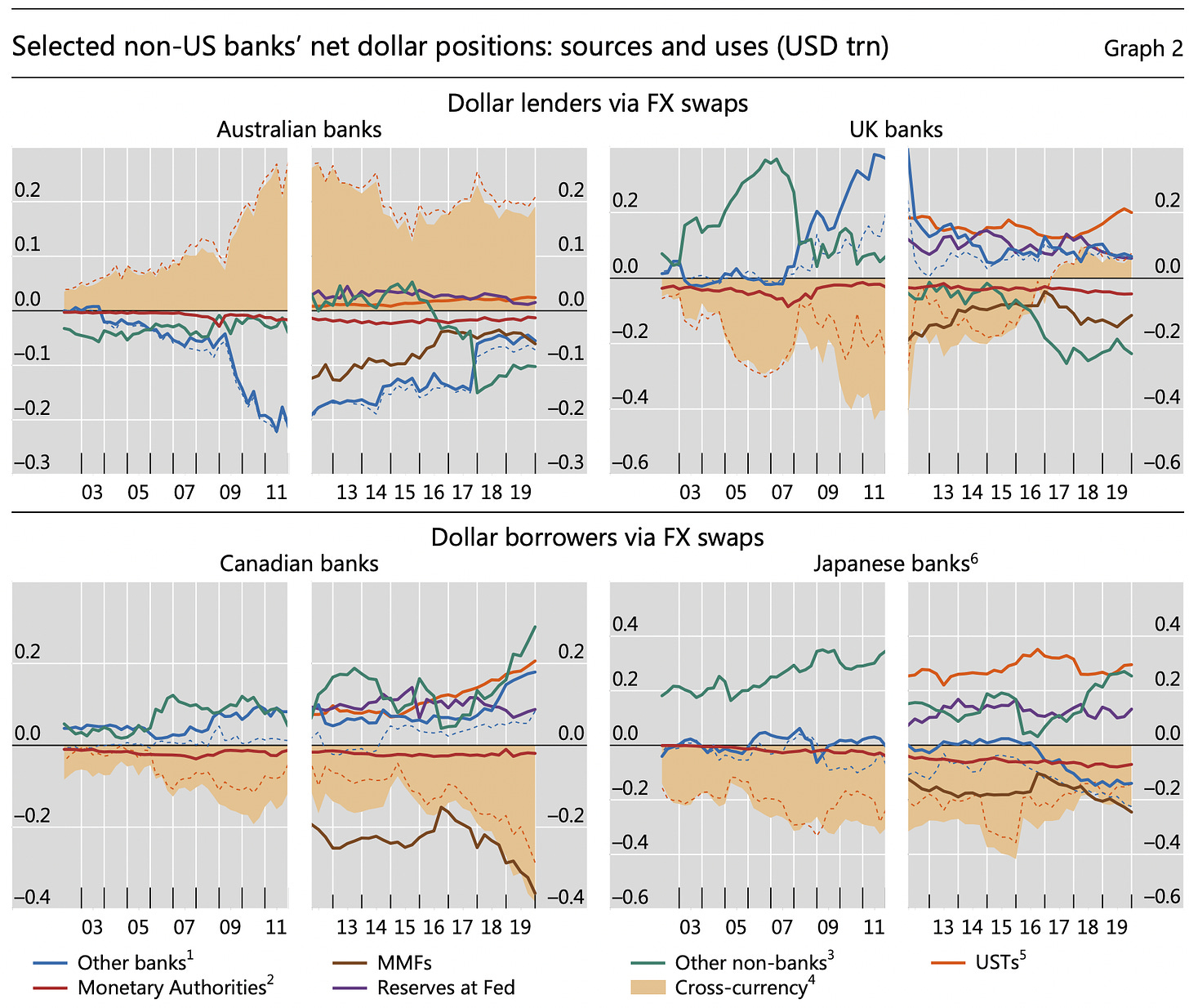

Under America’s security pact, the financial giants of the world swiftly took advantage. The major U.S. banks set up branches not just in the U.K. — which grew to become the epicenter of Eurodollar activity — but worldwide. Major foreign banks then set up operations within the U.S., primarily in New York. This, combined with a prolonged period of heightened peace, not only gave rise to the most stable reserve currency on record. Financial behemoths had created the global dollar funding complex, featuring over 25 different types of dollar-denominated instruments, from FX swaps to reverse repos to commercial paper.

The global dollar funding complex helped spin intricate webs that provided dollars to anyone within America’s global security pact, but especially to those outside America’s borders. Introducing: the Eurodollar system.

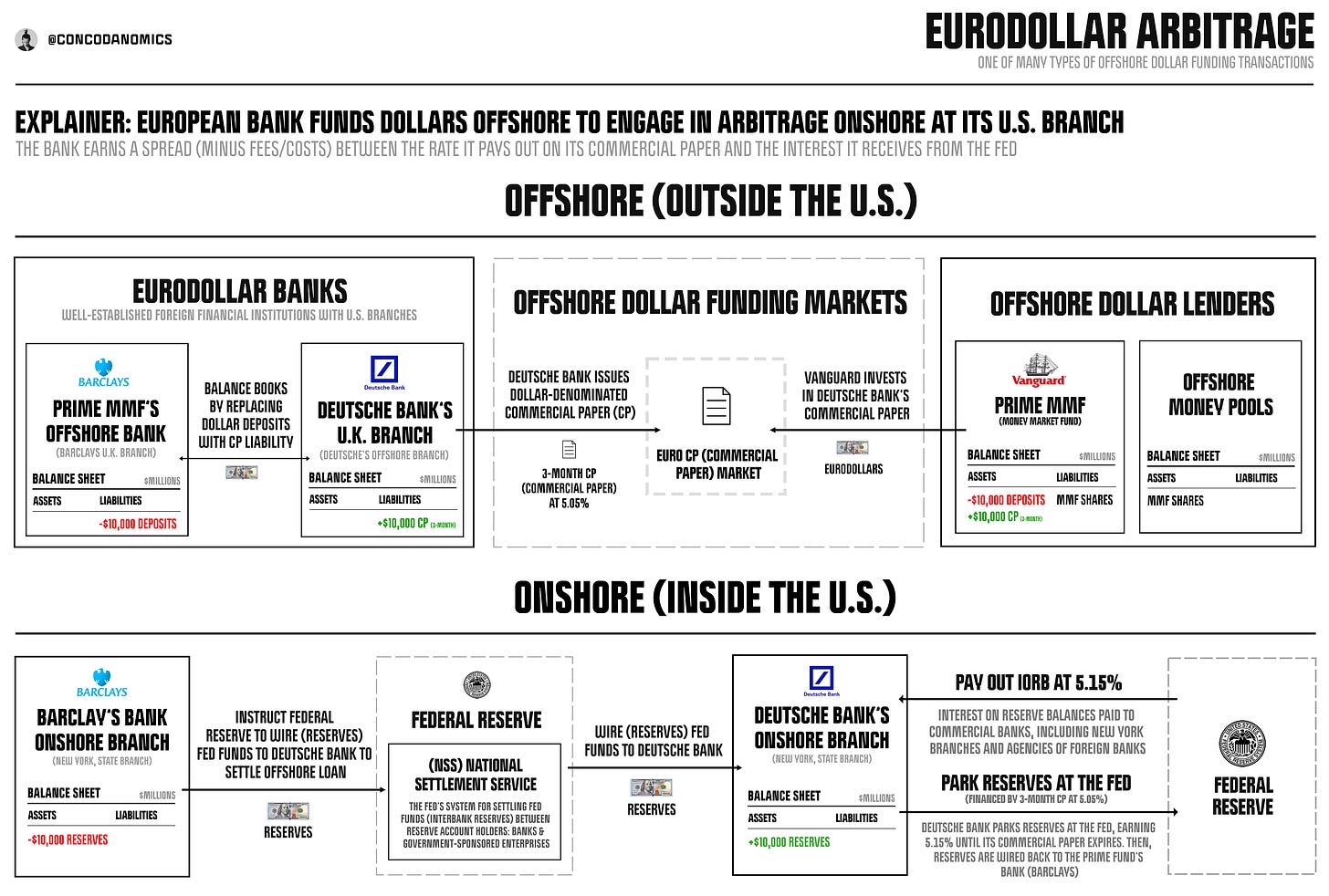

The arbitrage above is one of many varieties of trades occurring in Eurodollar markets daily and reveals what “Eurodollars” have grown to become in the modern era of banking. But what exactly is occurring here? Let’s investigate.

A European bank (Deutsche Bank) is seeking to attract offshore dollar deposits solely to engage in arbitrage at its U.S. (onshore) branch in New York. In simple terms, Deutsche Bank is trying to profit from the rate between offshore dollars (dollar-denominated commercial paper in Europe) and onshore dollars (Federal Funds .i.e bank reserves).

Deutsche Bank issues CP (commercial paper) to an offshore prime money market fund, which pays the German bank using an offshore dollar deposit. The purchase of CP removes dollar deposits from the prime fund’s bank account at Barclays offshore branch and adds reserves to Deutsche Bank’s onshore master account at the Federal Reserve. Deutsche Bank then parks these reserves at the Fed for three months, earning 5.15% until its commercial paper expires. Upon expiration, the transaction is reversed. Deutsche Bank sends reserves back to Barclays, which then credits the prime fund’s offshore bank account with an equivalent dollar deposit. No borrowing or lending of reserves even occurs. It is the settlement of the dollar loan that causes the transfer of reserves, making the arbitrage trade possible.

By issuing offshore debt to dollar lenders, dollar borrowers (usually arbitrageurs) earn a profit on the reserves they acquire from the lender’s onshore bank, which settles the offshore dollar loan transaction. The dollar loan is booked offshore by removing a dollar deposit and replacing it with short-term debt instruments and is settled onshore with Federal Funds (bank reserves). The banks involved, Deutsche Bank and the prime fund’s bank (Barclays), clear the transaction offshore by updating their offshore banking records. Meanwhile onshore, Barclays sends Deutsche Bank the loan amount in onshore dollars (reserves). The German giant earns a profit on the spread between its offshore dollar funding costs (the rate it pays out on its commercial paper) and the rate the Fed pays on onshore dollars (reserves). In this instance, that is 5.15% (IORB or Interest On Reserve Balances) minus 5.05% (the rate on 3-month commercial paper), equalling a 0.10% return.

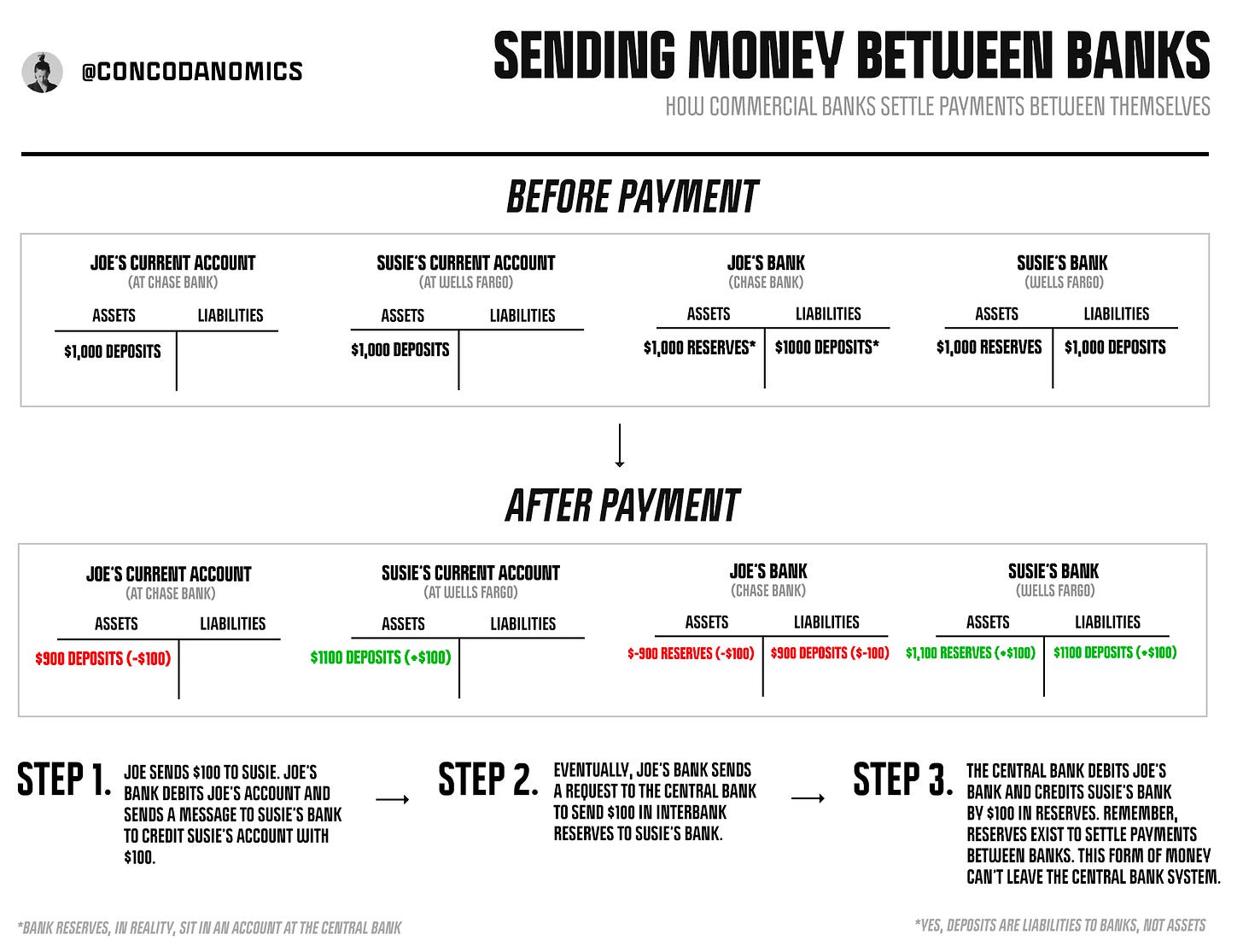

The way reserves are transferred in this trade is precisely the same as how payments settle between banks onshore (see below), but Eurodollar deposits clear in bank accounts offshore — or, in rare occasions, international banking facilities set up by the Fed.

The Eurodollar system, however, is much more than arbitrage trading. It’s a fully-functional banking system. Enabled by America’s global security pact, every major global bank is now plugged into almost every other country’s financial infrastructure. Most financial innovation that materialized inside the U.S. was swiftly replicated overseas, and vice versa. Soon enough, countries were not just using the Eurodollar system. They became part of it and helped build it out over multiple decades. Financial players in particular countries specialized in providing other nations with the dollar instruments they required, mostly without the U.S. authorities ever getting involved.

Since the Eurodollar system has been assembled by all the well-known financial institutions, offshore infrastructure is fairly similar. All the significant lenders and borrowers who participate in global dollar funding markets have longstanding relationships and operate entities that both borrow and lend dollars offshore. Prime money market funds, for example, have connections to all the big dealer banks globally. What’s more, these funds are likely to be operated by the same firms. JPMorgan, for instance, now runs a bank, a securities dealer, and an asset management business — but via separate entities because of regulation.

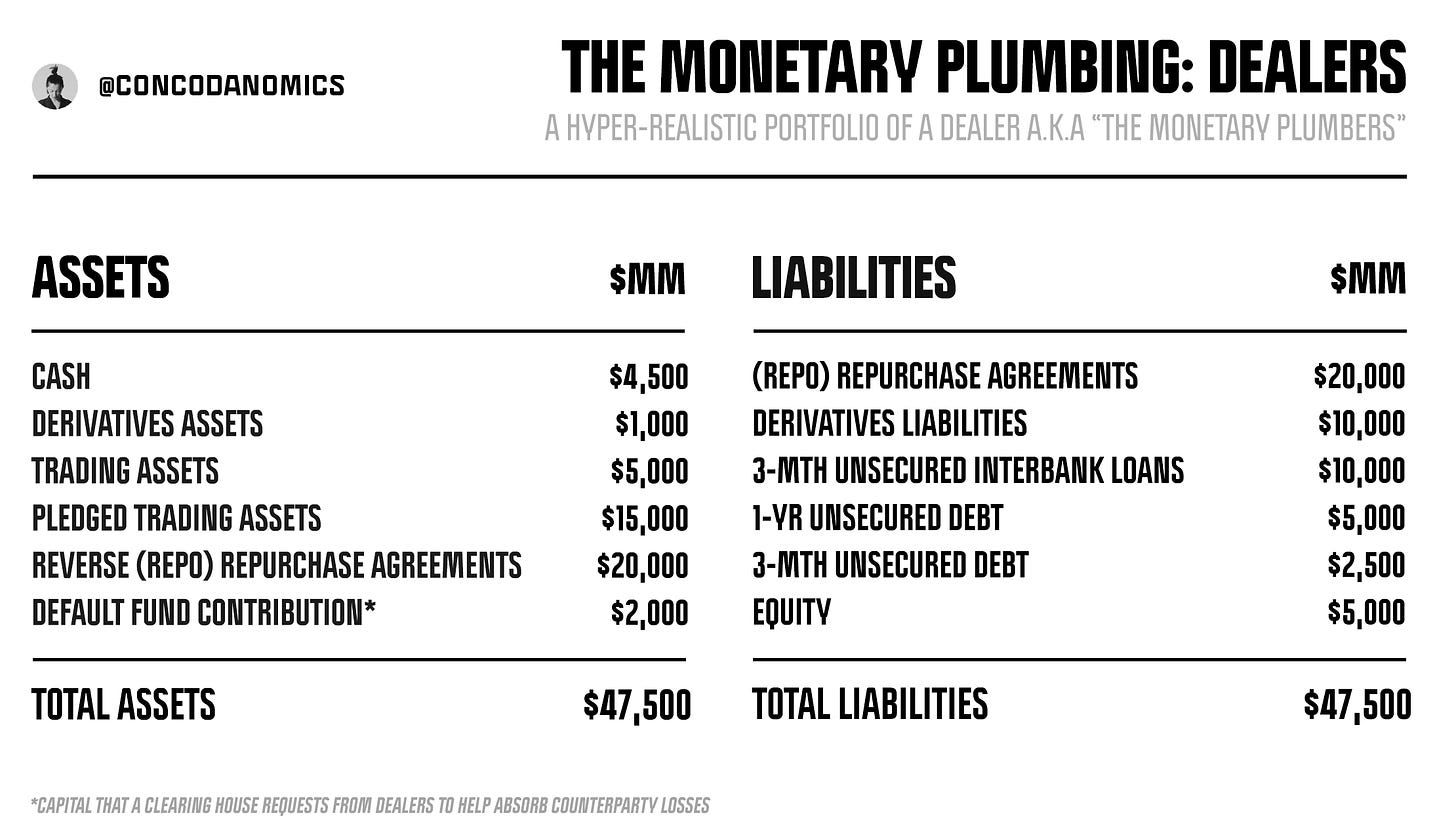

Much like the onshore system, the Eurodollar system connects cash lenders and borrowers via dealers and dealer banks’ “matched books”. Dealers provide dollar liquidity by borrowing dollars and lending them out, earning a profit from the spread.

So when a lot of commentary paints a picture of the Eurodollar system as mysterious and obscure, we would push back a little. The narrative that it’s a totally opaque system that exists in a parallel world is somewhat peculiar. Firstly, Fed Funds and Eurodollars are considered by the top financial behemoths to be almost fungible. The main difference is that Fed Funds can only be loaned out to those with a Federal Reserve master account (which grants access to the Fed Funds market), while a wider range of financial institutions can access Eurodollars. Regulators and authorities also not only keep track of Eurodollar transactions through brokerage data (yes, there are actually brokers for bank reserves) but they have permitted and encouraged what some deem illicit Eurodollar transactions for decades.

The modern Eurodollar is simply dollar funding and banking offshore that settles onshore, only because the U.S. empire has yet to set up the infrastructure to settle payments between banks outside its borders. This means the Eurodollar market allows foreign banks to go into the dollar lending business without having direct access to the Fed’s balance sheet. Only a few entities are authorized by the Fed to hold bank reserves — which are liabilities of the Fed — on their books. Everyone else must engage in “global regulatory arbitrage,” collaborating with entities that have access to the Federal Reserve System to settle dollar payments. There’s even a thriving market for Eurodollars within the U.S. because not all financial entities operating onshore that require dollar funding have access to the Fed’s balance sheet. Bank reserves cannot leave or be used outside the Federal Reserve System, let alone the real economy.

Another inaccurate description we see often is that banks outside the U.S. are just creating unlimited dollars out of thin air. In reality, banks active in the Eurodollar market are more careful about who they lend to because they do not have access to an immediate lender of last resort .i.e the Fed. Their central bank will have a swap line agreement with the U.S. central bank to access dollars in times of crisis, but it is not assured and not imminent. The U.S. security pact encourages global finance to provide a steady stream of dollars overseas so that the Fed and the Treasury can focus more on domestic monetary issues and avoid having to administer a global dollar policy. Still, all the Fed and U.S Treasury have to do to become the international dollar lender of last resort is fire up swap lines and the Fed’s FIMA facility (for China), whenever the supply of offshore dollars grows scarce.

Coincidentally, the supply of unsecured offshore dollar funding has dried up. After the GFC (Great Financial Crisis), a series of stringent regulations imposed on banks reduced the supply of Eurodollar funding, seemingly forever. The Basel Framework’s LCR (Liquidity Coverage Ratio) — which requires 1:1 backing of stable funding (reserves) for every short-term unsecured dollar raised — destroyed the major motivation to transact in Eurodollars. Then, shortly after, the SEC’s money market reform in 2014 caused a silent run on prime money market funds, the main liquidity source for Eurodollars. Eurodollar volumes today still average around $100 billion daily, but that pales in comparison to before the GFC.

Ultimately, the Eurodollar system is still active but plays a less significant role, not because the U.S. dollar is dying, but because of global regulatory changes. In the new “SOFR standard” that monetary leaders have enforced, secured debt instruments (like repos) have superseded their unsecured debt counterparts (like commercial paper), which provided the most unsecured offshore funding. As the effects of this monetary evolution have yet to be felt, we’re now in “secured but uncharted” territory.

That’s a wrap! We’ll cover Eurodollars again in relevant future pieces. If you have any queries or need clarification on any minor details, leave a comment below.

If you liked this, feel free to hit the ♡ button to let us know and share a link via social media to help us grow. Comments are also encouraged. Thanks for being a Conks subscriber!

I’m not sure I understand the payment process.

Please, could you confirm if the following is accurate? Thanks you so much.

Vanguard has a dollar denominated account at Barclays U.K.

Barclays U.K. has a dollar denominated deposit at Barclays U.S.

Deutsche Bank U.K. has a dollar denominated deposit at Deutsche Bank U.S.

Vanguard orders Barclays U.K. to pay 10.000 $ to Deutsche Bank U.K. (payment for the C.P.)

Barclays U.K. instructs Barclays U.S. to debit his account by 10.000 $ and transfer that sum to Deutsche Bank U.S.

Reserves (10.000 $) are wired to Deutsche Bank U.S. and then Deutsche Bank U.S. credits the dollar denominated account belonging to Deutsche Bank U.K. by 10.000 $.

10.000 $ (deposit) have been extinguished in Barclays U.K. account belonging to Vanguard (replaced by C.P.) and in Barclays U.K. account at Barclays U.S.

10.000 $ (deposit) have been added in Deutsche Bank U.K. account at Deutsche Bank U.S.

10.000 $ (reserves) have been extinguished in Barclays U.S. master account at the FED and 10.000 $ (reserves) credited in Deutsche Bank U.S. master account at the FED.

Nice one Conks! Definitely cleared up a couple misconceptions I had about the ED system, but most importantly it frames the transition to the new SOFR based secured funding model. Can’t wait for the next piece. Thanks for your good work!